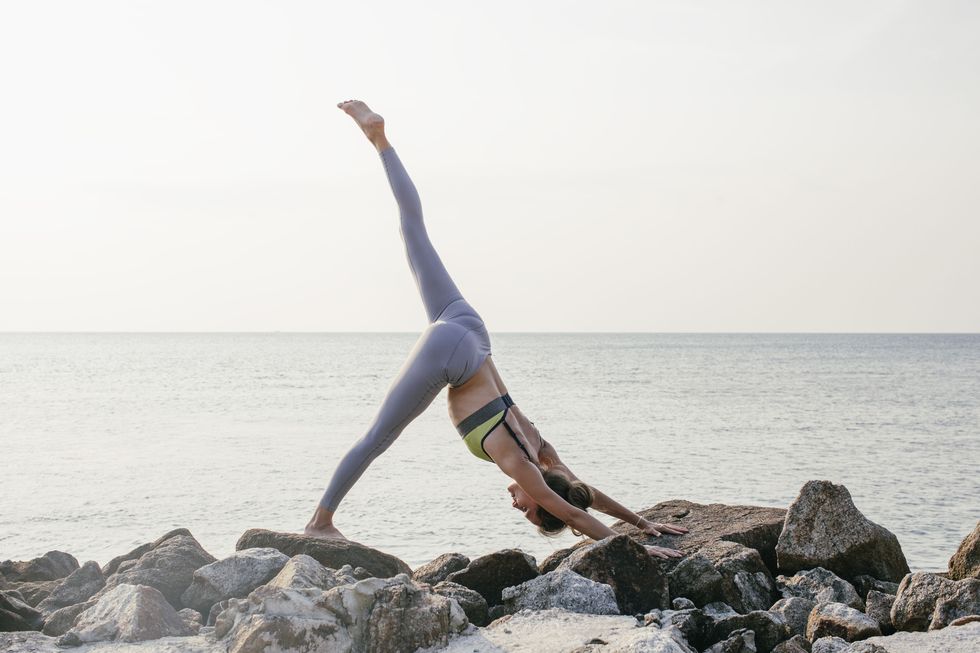

Whether it's an inspiring message on Instagram to 'get strong, not skinny', a #fitspo image of personal trainer on Instagram doing squat jumps, or side-by-side transformation photographs, it doesn't take much for a social media user to feel motivated to hit the gym for an early morning workout.

However, there's a fine line developing between those who want to work out to stay healthy, strong and fit, and those who push themselves to their physical and mental limits. Those who feel ashamed when they miss a workout, and punish themselves for failing to put their '110 per cent' into a training session.

I myself have also been guilty of falling into this trap.

In a bid to tone up for a beach holiday in March, I found myself on the verge of tears one day after work when public transport delays almost made me miss my weekly HIIT session, such was the feeling of overwhelming guilt at the thought of failing to stick to my rigid fitness plan.

However, rather than 'exercise addiction' being used in a relatively light-hearted way in conversation among friends, in the same vein we talk of addictions to chocolate, wine and Love Island, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) are now recognising it as a serious medical issue. They've addressed the issue in their latest paper 'Addiction to exercise'.

Here's what you need to know about 'exercise addiction':

What is 'exercise addiction'?

The BMJ describes people with exercise addiction as experiencing a 'loss of control such that exercise becomes an obligation and excessive'. While it's not classified as a mental health disorder, it is characterised by 'similar negative effects on emotional and social health as other addictions'.

What is primary and secondary exercise addition?

According to the British Journal of Sports Medicine, primary exercise addition happens when the exercise is the main aim of the practice, whereas secondary exercise addition is often a consequence of an eating disorder and a means to control weight.

Is it really that common?

It's hard to tell how common exercise addiction is among fitness fanatics due to the lack of 'sustained and methodically rigorous research', according to the BMJ. However, an Italian study from 2014 titled Unraveling Exercise Addiction: The Role of Narcissism and Self-Esteem found that over 40 per cent of the 120 gym-goers who took part in their research were found to be at risk of the condition.

Laura Stokoe, 25, from Liverpool is all-too familiar with this risk. From the age of 17, she was exercising extensively - an hour-and-a-half of cardio every day - with very little food intake in order to lose weight.

'I used to get a bit of a high off it whilst I was working out and enjoyed the attention as people noticed I was losing weight and telling me how good I looked,' she explains.

Six months ago, however, she suddenly realised the extent of her condition. She was training six times a week for around two hours each day.

'I realised I was addicted when I hurt my knee and couldn't train for a couple of weeks. It dawned on me how draining, unbalanced and obsessive my exercising patterns were. I lived and breathed exercise - I told myself I loved it,' she says.

Who is at risk?

The Italian study found that people who strongly identify themselves as an exerciser and have low self esteem are more at risk, as are people who struggle with anxiety, impulsiveness, and extroversion.

Although men and women are equal at risk, primary exercise addiction is more common among men, whereas secondary is more commonly associated among women.

How can you tell if someone is suffering from 'exercise addiction'?

It's important to realise that any addictive behaviour doesn't happen over night.

The BMJ points out that injury, anaemia and amenorrhoea are common indicators of overtraining, as are unexplained decreases in performance, persistent fatigue, and sleep disturbance.

Sufferers might also be more likely to drop social plans or family obligations, or report withdrawal effects such as sadness, restlessness and anxiety when opportunities arise that might conflict with their plan to exercise.

This is an experience 25-year-old Mairi-Claire Get Tay from London has been victim of in recent months.

Having increased her workouts to five times a week last year, she soon found herself beginning to lie to friends about her social life so they wouldn't become suspicious of her addiction to exercise.

'I would be sheepish and moody when someone made a comment about me going to the gym instead of spending time with them. Sometimes, I'd even lie if I was going to the gym and say I was seeing another group of friends,' she says.

She believes her obsession with the gym was triggered by a break-up, after her ex-boyfriend suggested one of the reasons for the split was due to her lack of exercise. 'It made me determined to show him wrong. I started watching YouTube videos and became Instagram obsessed,' she admits.

However, Mairi-Claire soon became aware of her unhealthy addiction to exercise when she started to develop pains in her shins from running. 'I was still determined to go out and run my weekly 10km. I ended up in agony and struggling to walk for a month.

'At the time I did feel bad, but the fear and worry about pilling on the pounds was far stronger,' she adds.

How is it diagnosed?

'Exercise addiction' is believed to be diagnosed on clinical judgment. The BMJ states that treatment will often involve patients being helped to understand why they want to train so much, their emotional relationship with exercise, and how it affects other parts of their lives.

It's important to point out that those addicted to exercise should not be described as being obsessive-compulsive with the practice. Addicted exercisers enjoy what they are doing, whereas the latter disliked it but are compelled to do so.

Primary school teacher Naomi Savory admits it is only in the last few years that she's finally overcome her addiction, after being diagnosed with anorexia at the age of 18.

During her recovery, the 25-year-old says she continued to have a problem with exercise and often felt guilt and shame if she didn't exercise daily. 'I was finally at a healthy weight and eating normally but couldn't kick my gym addiction,' she reveals.

However, Naomi's current boyfriend has helped her gradually understand her addiction to the gym was abnormal and learn to love exercise again.

'We started to plan time together a few nights a week instead of me going to the gym. He supported me when I felt out of control or guilty. We would go for walks together and this helped me to realise I could exercise for enjoyment rather than guilt,' she says.

By slowly introducing gentle exercise such as yoga into her fitness routine, Naomi now enjoys regular pole dancing classes and a couple of gym sessions during the week.

'I now exercise to take care of my body not as a punishment,' she says.

How is it treated?

Like most behavioural addictions, cognitive behavioural therapy and dialectical behaviour therapy are recommended to help patients rethink how they value exercise and manage mood disturbances. The goal of treatment is to help people recognise the addictive behaviour and reduce the rigidness of their exercise plans.

If you feel like you might be suffering from exercise addition, the BMJ suggests considering the following questions:

- How often do you exercise?

- How long is your typical workout?

- Why do you exercise?

- What are your goals that you hope to achieve through your exercise routine? How did you decide on the exercise routine your currently perform?

- How do you know when you have exercised too much or reached your personal limits?

- If you feel you have done too much, what do you do to ensure that you recover properly?

- How do you know when you are ready to resume your normal exercise routine?

- When you have been ill or injured, do you continue to exercise? If so, how do you modify your training to accommodate the illness or injury?

- Does your exercise schedule frequently conflict with your work, school, family, or social obligations or interests?

- If so, what do you feel are the consequences of these conflicts?

- How do you feel when you are unable to exercise or have to modify your exercise routine?

- Determine if the patient balances exercise with other leisurely activities

- Do you engage in any other activities in your free time?

If you think you are currently suffering from 'exercise addiction' or would like further information on the issue, please consult a medical profession or book an appointment at your local GP practice.

Katie O'Malley is the Site Director on ELLE UK. On a daily basis you’ll find Katie managing all digital workflow, editing site, video and newsletter content, liaising with commercial and sales teams on new partnerships and deals (eg Nike, Tiffany & Co., Cartier etc), implementing new digital strategies and compiling in-depth data traffic, SEO and ecomm reports. In addition to appearing on the radio and on TV, as well as interviewing everyone from Oprah Winfrey to Rishi Sunak PM, Katie enjoys writing about lifestyle, culture, wellness, fitness, fashion, and more.