The term "second-wave feminist" has started to sound like an insult. Last week, Babe.net reporter Katie Way hurled it at TV reporter Ashley Banfield, calling her a "burgundy-lipstick bad-highlights second-wave-feminist has-been," among other colorful descriptors. Jezebel writer Stassa Edwards was more measured when she deployed it in her piece titled "The Backlash to #MeToo is Second-Wave Feminism." And in a tweet, the Verge's Laura Hudson, though she did not invoke the second wave explicitly, drew social-media ire when she suggested that it was time for older feminists "to listen, to learn, to step aside" because "age tends to correlate with not being on board with progress[.]"

All this recalls a familiar conflict. Younger feminists have been blaming "the second wave" or "older women" for decades. In the 1990s and 2000s, second wavers were cast as the shrill, militant, man-hating mothers and grandmothers who got in the way of their daughters' sexual liberation. Now they're the dull, hidebound relics who are too timid to push for the real revolution. And of course, while young women have been telling their forebears to shut up and fade into the sunset, older women have been stereotyping and slamming younger activists as feather-headed, boy-crazy pseudo-feminists who squander their mothers' feminist gains by taking them for granted. It's a debate that we've been having, fruitlessly, for over 20 years.

To be fair to young women, it's absolutely true that some Gen-X and Baby Boomer women have been speaking up to accuse the #MeToo movement of victimizing men (Caitlin Flanagan, Margaret Atwood) or making sex unsexy (Daphne Merkin, Catherine Deneuve) or spreading "hysteria" (Katie Roiphe) or just being lying ho-bags who secretly like being harassed (Brigitte Bardot). It's also true that Hudson has been clear that she does not mean all older women, and Edwards is specific in critiquing "liberal," mainstream second-wave feminists; I like and respect both women's work, and don't want to undermine either one by chiming in here. But to frame all this in the age-old dialogue of "second-wavers" versus younger, "better" feminists risks mischaracterizing, not just the work of older activists (who rightfully feel misrepresented and erased by these tropes), but the actual power dynamics at play in the backlash.

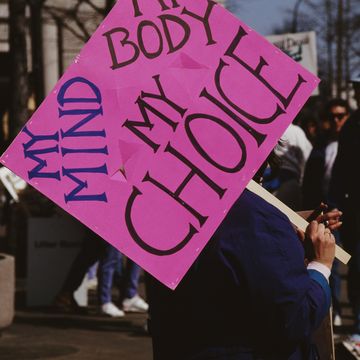

It may be useful to define our terms here. "Second-wave feminism" refers to the activism of the 1960s and 1970s, which encompassed the most widely known feminist causes: Workplace parity, abortion and birth control access, and an end to sexual violence. This wave tapered off in the 1980s, though it never fully died out. The "third wave" covered the 1990s and early 2000s. It's known for sex-positivity, an increased focus on pop culture, and reclaiming "girliness" and femme gender presentation. The current wave—which has been called fourth-wave feminism, millennial feminism, or just "feminism," period—has somewhat blurrier boundaries, but arose somewhere around the late 2000s and early 2010s, through the explosion of feminist blogging and social media. It's known for its digital literacy and emphasis on intersectionality.

The biggest problem with blaming second-wavers for standing in the way of #MeToo is that, without the second wave, we probably wouldn't have #MeToo in the first place. A partial list of what we owe second-wavers: The idea that rape and domestic violence are crimes of misogyny (Susan Brownmiller's 1975 definition of rape as "a crime not of lust but of violence and power" has been the go-to feminist explanation for decades); the criminalization of "lesser" assaults like spousal rape; the first rape crisis centers and women's shelters; the first large-scale anti-rape protests; and the concept of "workplace sexual harassment," introduced to the public by Anita Hill and pioneered by second-wavers like Catherine MacKinnon, who published a book arguing for sexual harassment as a form of gender discrimination in 1979.

But this isn't to suggest that second-wave thinkers were faultless. In fact, some were markedly problematic. Brownmiller's Against Our Will, in particular, was called out by other second-wave feminists for its intense racism and stereotyping of black men as rapists. (In 1976, Alison Edwards called it "a book which, unless repudiated, will serve to fan the fires of racism," noting that Brownmiller called the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till mere "overkill.") But no generation has a lock on bad ideas. Millennial feminism has been dogged by racism and oppressive thinking, too. Hence: "white feminism," a term created to account for it, and self-proclaimed feminists like Ivanka Trump, who claim the descriptor but do little to stand up for its aims.

But the problem with how second-wave feminism has been characterized over the past few months isn't that its actual contributions to sexual politics have been misrepresented. It's that most of the women who've been implicated, the ones who claim #MeToo has gone too far or worry about the fate of men—they don't appear to be second-wave feminists, or even just plain feminists, at all. Caitlin Flanagan, who made a name for herself with arguments including that young women are too promiscuous and that mothers shouldn't work outside the home, has always been conservative. Brigitte Bardot is a far-right extremist who has been brought to court multiple times on charges of "incitement to racial hatred." Katie Roiphe, whom Edwards cites in her piece as a key voice in the second-wave backlash, became famous in the early 1990s for her proclamation that her fellow college students were overreacting to date rape. In fact, she's never been a feminist, and if she were, the timeline would place her in the third wave—where she'd meet Daphne Merkin, who made headlines in 1996 after she published a piece in the New Yorker about all about spanking.

That's not a coincidence. Yes, there are some second-wave feminists participating in the #MeToo backlash—at least, there's one; Margaret Atwood is firmly in the second wave—but to the extent that these critiques resemble any of the feminist ideologies, they mostly resemble a warped, toxic take on the third wave's call for a sex-positive culture. (These reactionaries seem to use that frame to accuse women of "self-victimization," when what women have really asked for is respect.) In other words, the fight isn't between now and the second wave or even cleanly between any two waves of feminist thinking. So it's worth investigating why the oldest living generation of feminists is being taken to task—or, more precisely, why we can't let go of the idea of a conflict between "them" and "us."

Especially over the past decade, much has been made of the divide between older and younger feminists. During the 2016 election, the media obsessed over a "generation gap" between them, which manifested in their uneven levels of enthusiasm for Hillary Clinton. In 2008, "Obama girls" were supposedly driving their Clintonista mothers up the wall. And throughout the 2000s, feminist bloggers who wrote about booze and sex were said to be ruining the once-serious movement. (The 1960s, when the second wave exploded, wasn't a time exactly lacking in recreational drug use or casual sex. Unsurprisingly, the press write-ups tended to gloss over that.)

In 2010, during yet another of these intergenerational scraps, Katha Pollitt complained that the "new wave" talk was used "to describe each latest crop of feminists—loosely defined as any female with more political awareness than a Bratz doll—and to portray them in terms of their rejection of second wavers, who are supposedly starchy and censorious."

"The wave structure," she continued, "...looks historical, but actually it is used to misrepresent history by evoking ancient tropes about repressive mothers and rebellious daughters."

And feminists themselves fall into those. Third-wave icon Kathleen Hanna once explained that she based herself in "opposition to what I perceived as being Second Wave feminism. I was like, 'I'm a SEXY feminist, and I'm going to wear makeup and blah blah blah.'" But when Hanna looked into the movement against which she wanted to define herself, "I realized that I was playing into stereotypes, and that I didn't need to base myself in opposition to my perception of the past," she said.

By asking young women to devour their predecessors in order to feel empowered and unique, we've created a culture where feminist narratives are rolled up behind us like a carpet, rendered invisible the moment we're able to build on them. This has left many older women wounded, believing (not unjustly) that they're being blamed for not understanding the ideas they originally contributed to the conversation. But it also does no great service to young women—the ones at work now or the ones who will come after us—who can only feel that they constantly have to reinvent the wheel.

Feminism is, among other things, an intellectual tradition—and, as the writer Michelle Dean has pointed out on Twitter, other intellectual traditions get to have a real sense of their own history. Those histories can be ugly and contentious, as full of ideas to reject as they are full of inspiration, but they are also taught in schools, sold in bookstores, and shown on PBS in a way that encourages young people to view the past as a resource. In our culture, when women get past the age of 40, they're seldom viewed as a resource—more likely, we just ask why they haven't shut up yet. The media encourages young women to view older feminists as nemeses, not potential allies—and older women, all too aware that the culture wants to render them invisible, hold tightly to whatever power they've got rather than share it with younger activists. ("Get your own torch," second-waver Robin Morgan once chided young activists, "I'm still holding mine.") Resentment naturally builds, and the ability of women to work together across generational lines disintegrates accordingly.

If women are ever going to take over the world, we ought to get comfortable with the idea of matriarchy—matriarchs and all. Instead of constantly battling to see which "wave" of feminism will win out, or which generation is most worthy, let's simply call wrongheaded, regressive, and reactionary women what they are—wrong, and probably not feminists in the first place. There's no age limit on bad ideas, and we'll need all the waves for the coming flood.