Back in the summer of 2014, Annetta Dingle began having premonitions that something was going to happen to one of her four boys. She saw crows, a sign of death. At the beach one day, burying her grandson in the sand, she saw the image of a face. She called at least one of her boys every day to check up on them.

On Monday, August 11, 2014, Dingle was uneasy. Her dark thoughts hadn't cleared. All day, she had chest pains. Something wasn't right. It was around 9 p.m. and a counselor was just leaving Dingle's home in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. A recovering addict, Dingle had been seeing a therapist to help her deal with the incarceration of her youngest son.

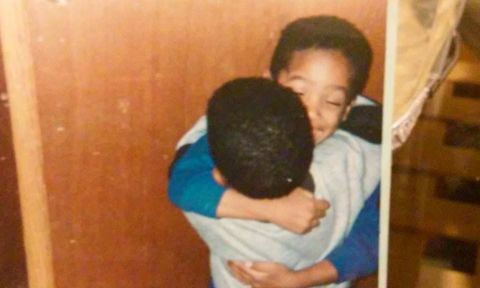

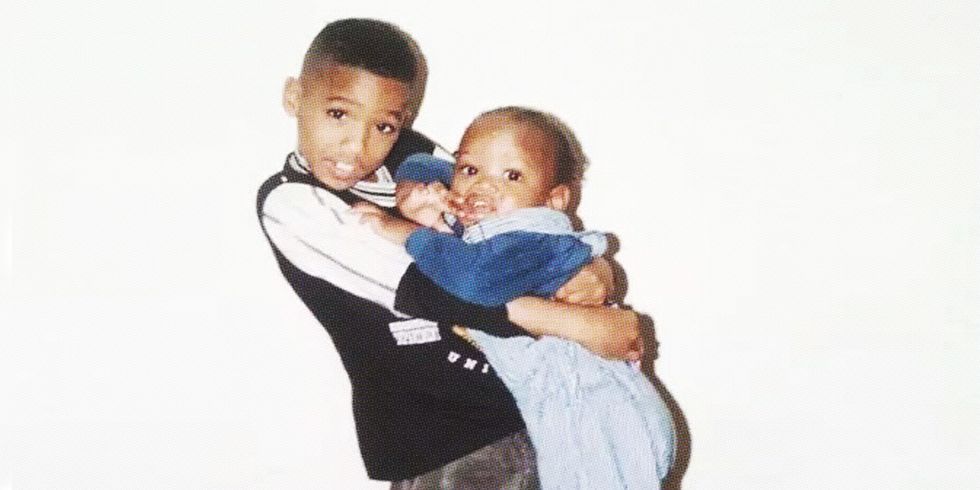

Once the counselor had gone, Dingle picked up the phone and called her son Anthony. Among her twin boys, Anthony and Antoine, Anthony was her weaker boy, the one with a lifetime of health problems, the one who needed to be protected. Ever since middle school, it was Antoine who had been the strong one. Dingle called him her "backbone," the son she could turn to when she was short on cash or just needed someone to talk to.

A few doors down from his mom's house, Antoine, then 27, arrived at the home of an acquaintance. He went into the house for a minute, and then went outside to wait for the neighbor. That's when, Dingle was later told, the men in hoodies came out from the alleyway across the street.

Dingle had just hung up the phone when she heard the shots. She ran to the front porch of her third-floor apartment, but before she got outside something stopped her. She ran down the stairs, out the front door, and down the sidewalk, where she saw Antoine on the ground.

"They got him!" she heard neighbors yell. Blood was pouring from the bullet holes in Antoine's back. He couldn't speak.

She started pumping his chest, doing CPR. After what seemed like an eternity, the ambulance showed up. They lifted her boy into the back of the vehicle and drove away. Alone in her car, Dingle followed the ambulance. She could see them working on Antoine through the windows.

When they arrived at Boston Medical Center, nurses tried to stop her from following Antoine into the ER. They told her to calm down. Within minutes, the doctors came out. The look on their faces told her all she needed to know.

The days and hours after the death are hard to for Dingle to remember. She recalls going into the room where her son's body lay. She remembers touching his still-warm skin and kissing him, staying with him until 4 a.m. She doesn't remember sleeping once she went home.

Someone videotaped the funeral, which was held eight days after Antoine's death. When Dingle watches the footage now, and sees the woman wearing the purple shawl—her son's favorite color—she doesn't even recognize herself. Everyone told her how strong she was, but she didn't feel that way. She didn't feel anything.

It took weeks for her to get back to work at the hair salon she owned. Having to go to work sometimes helped her get out of bed, but inside, she wasn't really there. She was still on that sidewalk with her son.

In the early days of her grief, Dingle tried attending recovery meetings. She went to church. She spoke to her counselor. But being out in the world meant talking to other people and hearing their unsolicited theories on her son's murder: Antoine was targeted; he was caught in the crossfire; he was the wrong guy. To Dingle, it didn't really matter. It still meant Antoine was gone.

In her neighborhood, she saw the women like her, the mothers who lost children to something worse than illness or accident. They all chose different paths. Some chose retaliation. Others chose drugs. Others, as she put it, "just lay down and die."

Dingle felt herself going that way. But then a flyer showed up at her house from the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute. Founded in 1994 by Clementina "Tina" Chéry after her son, Louis, was killed by errant gunfire, the Peace Institute operates out of a converted house on a dead end street in Dorchester. The staff work to help families who have lost a loved one to violence plan funerals, pay for burial costs, and survive those early days after a homicide. Dingle's was one of those families who received this assistance. But the aim of the Institute is larger: "Our goal is to create peaceful communities where all families can live," says Alexandra Chéry, the daughter of Tina Chéry. "That starts from within."

Not long before Antoine was killed, sociologist Stephanie Hartwell had gone to the Peace Institute with an idea. Hartwell has spent her career studying at-risk communities—juvenile offenders, men leaving prison, women in jail diversion programs, those with addictions. Over the last few years, the University of Massachusetts–Boston researcher had studied the effect of mindfulness on men about to leave prison. In 2014, she wanted to see how it would work for those who had lost someone because of a homicide. She approached the Peace Institute and offered them a trial: a series of four sessions. They spread the word via flyers, distributed in the neighborhood, one of which had landed in Dingle's hands.

Dingle warily attended the first class just a few months after burying her son. She felt like she was being set up. Her son's killers still hadn't been caught. What if someone was trying to harm her?

The instructor, Bonita Jones, told Dingle and the other women to "stay present," which was harder than it sounded. Her thoughts were still racing. She was still in fight or flight mode. But Dingle listened to Jones and closed her eyes.

Given the cultural prominence of mindfulness, it's not surprising that it's been co-opted and deployed in recent years as a way to deal with the most difficult things life throws at us. Mindfulness therapy has been studied as a means to address the scars of child abuse or the ravages of drug addiction. The Department of Veterans Affairs pushes its mindfulness app, while advertising the potential to quell PTSD symptoms. Hospitals are using mindfulness to stop burnout among doctors and nurses.

Some critics, though, say that mindfulness is a tool of the elite, and has strayed from its Buddhist roots advocating simplicity. Mindfulness apps—from Headspace to SmilingMind to iMindfulness—are only of use to those who already own a smart phone. Arianna Huffington's new venture, Thrive Global, will offer corporate workshops and seminars; the deck for the company estimates that global corporate wellness will be a $10.4 billion industry by 2018. The godfather of mindfulness, Jon Kabat-Zinn, warns of "McMindfulness."

But there are places, like the Peace Institute, that are trying to bring mindfulness to men and women who have not, traditionally, been consumers or advocates of the practice. At a clinic and community center just down the road from the Peace Institute in Dorchester, general practitioner Dr. Pamela Adelstein has been recommending mindfulness for her patients—many of whom are suffering from domestic violence, abuse, the loss of a child or sibling to violence. "I talk to them about how they can choose how they want to react, instead of responding," she says. Hortensia Amaro, a researcher at the University of Southern California, has adapted a mindfulness program for a group of low-income women in recovery for substance abuse in California. At a residential treatment center in Los Angeles, she's begun a trial that will use brain scans to measure the effects of mindfulness. In Rhode Island, the Prison Mindfulness Institute works with inmates and correctional officers to teach them meditation and other Buddhist practices.

And at the Peace Institute, the program continued beyond its pilot stage. The next round was an eight-week program with Dingle and 14 others. Most of the women were mothers. Five were childless, because their children had been killed. They all had one thing in common, Dingle says: "We wanted to still live successfully in spite of our anger or depression." Jones directed the women to breathe into wherever she felt comfortable, adjusting the practices when necessary. Even the sound of young men outside the building, or children playing on the sidewalk, could trigger some of the women. "It definitely was a learning curve," Jones says.

Having someone like Jones, a black woman who has spent years working with underserved populations (in addition to working at Boston Medical Center as an integrative medicine practitioner), made a difference. "There's still a wide range of people [mindfulness] has not reached," Jones said. "Not everyone has a smartphone to get an app." When Hartwell was conducting her research, she says she often heard the women dismiss the practice, saying "that's what white, skinny women do."

But despite initial skepticism, the findings by Hartwell and her team from the sessions at the Peace Institute were encouraging. A third of the women had post-traumatic stress disorder when they started, according to initial testing. (About 7 or 8 percent of the general public has PTSD, studies show. But almost a quarter of those who lose someone to homicide will develop PTSD—a higher rate than victims of direct crime.) Hartwell found the women were using mindfulness to regulate their emotions, feel more empowered, and better cope with their day-to-day lives. They also had less overall anger and more insight into aggressive behaviors. The PTSD symptoms started to fade. "The underlying point of mindfulness-based stress reduction is emotional regulation," Hartwell says. "You learn to say, 'I have this terrible feeling, but I'm going to let it go.'"

Dingle mostly speaks about Antoine in the present tense—"He's adorable," she says—before switching back to the past, as if she remembers, mid-story, that he's gone. The tears start to fall and she lets them, looking off out the window of her salon. Then she's back, facing forward, wiping her tears. "I miss my baby," she says.

That was mindfulness, she explains later. Talking about Antoine dredged up the overwhelming feelings of grief, then anger, then sorrow. She should be angry. His killer has never been caught.

Instead of resisting the memories and losing control, Dingle now faces them. She remembers what Jones told her. "She would tell us to embrace those moments," Dingle says. "Acknowledge that you're feeling it. And realize that this is not real right now." Dingle's mindfulness practice is something she can access at any time. "It gives me skills I can utilize at three in the morning."

Dingle now wakes up an hour before she needs to. She scans her body for the aches and pains and pleasures. She looks at a collage of photos on her bathroom door—mostly Antoine. She closes her eyes, and thinks about her son. For the first time in her life, she can hit a pause button. The hour in bed thanking God and thinking about her son are for her.

Dingle is only two years into her journey of loss. She looks at the women who are into their second or third decade, and sees how fresh it still is to them. She doesn't want to feel like them. And she doesn't think she will. She can talk about Antoine. She can remember him. She can live without him. "You can live through it," she says. "But how well you live through it is totally up to you."

Allison Manning is a Boston-based reporter who has covered crime and violence for news organizations in Massachusetts and Ohio.