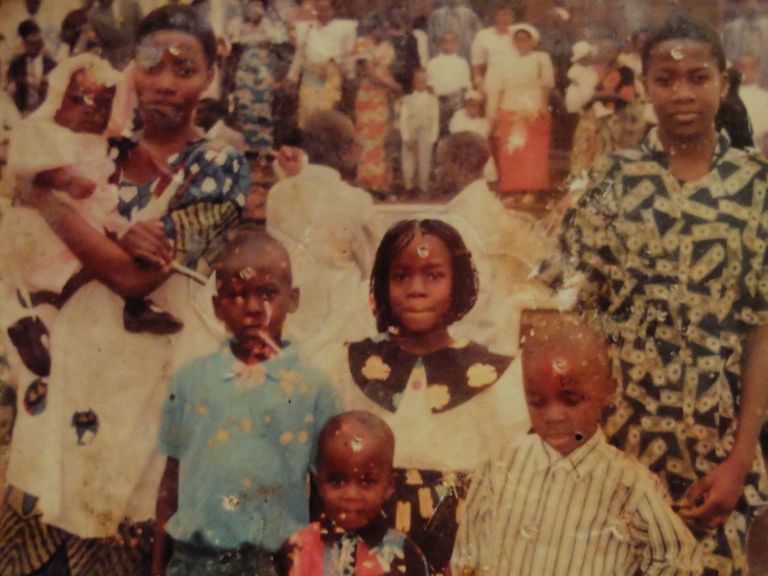

From where she sat on a friend's couch in Lexington, Kentucky, Jacqueline Kosongo Rukevya felt a brief wave of comfort. The living room buzzed with warmth and motion. A gaggle of kids huddled around the television, while the clatter of cookware and smell of familiar foods wafted from the kitchen. Back in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Jacqueline's life had also been full of spicy aromas, family and, most important, her six children. She would give anything to have it back.

Jacqueline's friend Rehema was also a refugee from the DRC. After Jacqueline, 38, arrived in Lexington in October 2015, the two women grew close on regular bus trips to Lexington's resettlement agency, Kentucky Refugee Ministries, and, later, while searching for jobs together.

Unlike Jacqueline, Rehema and her family had escaped from the war-torn DRC in time, fleeing the violent clashes between the corrupt government and dozens of vicious rebel groups, and taking shelter in a Ugandan town. Jacqueline had waited too long to run. By the time she arrived in a refugee camp in Malawi, her family was slaughtered or missing. During her eight years in the camp, she had searched for her children. By now, she knew she would not find them.

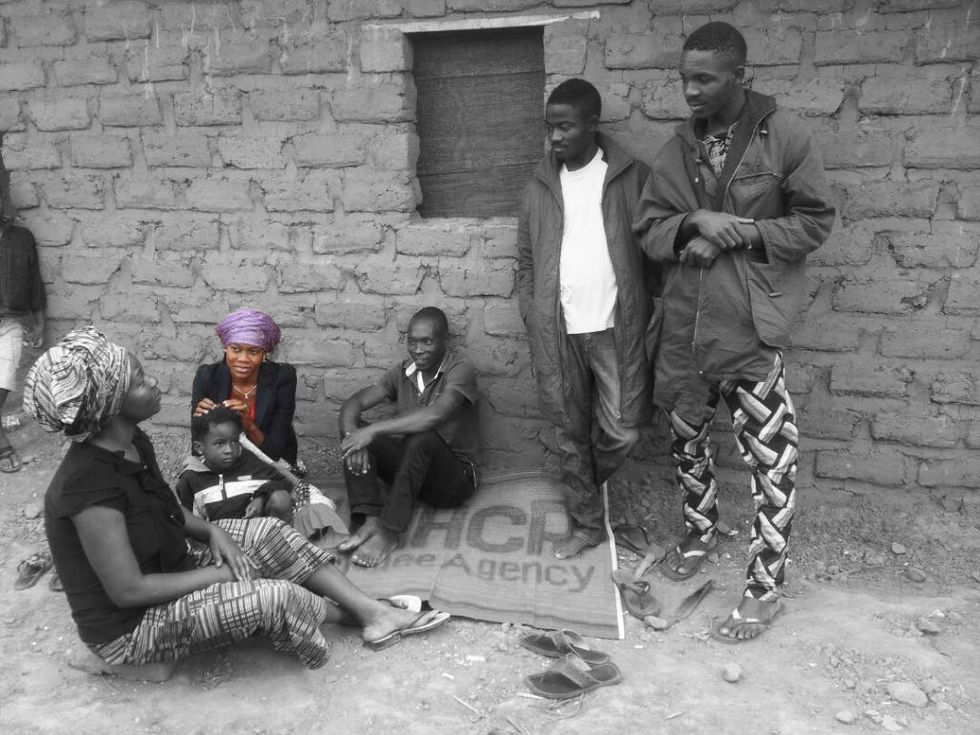

As they talked about their lives before America, Rehema showed Jacqueline pictures that Rehema's brother had sent from Uganda. Jacqueline paused on a picture of a small group gathered around a plastic mat. A girl in a purple head wrap sat in the back, her eyes drifting off to the side, out of the frame. The girl was thin, but her features mirrored Jacqueline's own: She had light and smooth brown skin, warm brown eyes and high, aristocratic cheekbones.

The girl's eyes were familiar, but they belonged to another era — that irretrievable time eight years ago, when Jacqueline had a house and a family. Ponga, her eldest daughter, had had eyes like that. But it didn't seem possible. Jacqueline couldn't imagine that her children might be alive.

"This child here, in this picture," Jacqueline asked, "do you know her name?"

Rehema didn't know. But the next day, as the two women caught a bus to continue their job search around Lexington, Rehema told Jacqueline that she had called her brother. He knew the name of the girl in the picture. Ponga.

For a moment, Jacqueline's heart went weightless.

The massacre that destroyed Jacqueline's family happened almost ten years earlier, in May 2007. Jacqueline and her six children were asleep in her house when a mob of neighbors appeared in her courtyard, their hands gripping machetes, knives, sticks, and guns.

She knew why they were there: Her decimated community in the South Kivu province believed her family were traitors. When the rebels and government militias came, slaughtering and ransacking the village, Jacqueline's family was the only one that had survived intact. The grief-stricken community wanted to even the score. In the chaos of the massacre that night, amid beatings, murder, and rape, Jacqueline's family — her father, mother, siblings and children — scattered.

Jacqueline had no choice but to escape. Her mind felt shattered, but she recalls a car and a boat as stepping stones in her flight. She made it to a camp in Malawi and registered as a refugee with the United Nations. She felt wholly broken, drifting between church groups, aid workers and trauma counselors who tried to coax her soul back into her body. The Red Cross's searches for her children came up empty. Jacqueline knew that if she went home to look for them, she would be killed.

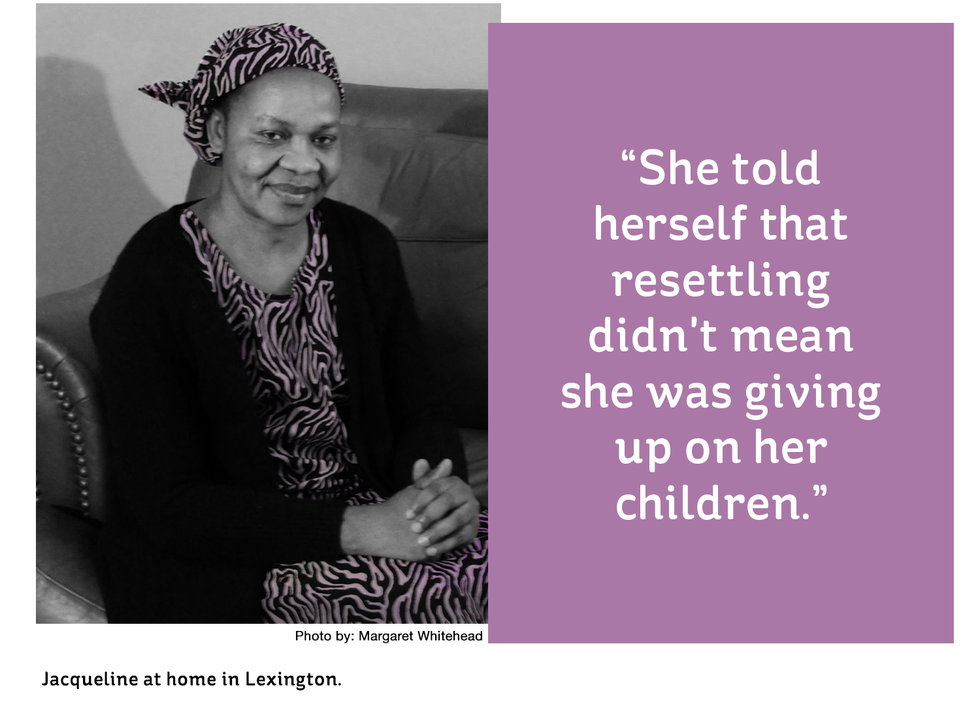

In 2014, after seven years of living hand to mouth in the refugee camp, Jacqueline hit a stroke of luck that less than 1 percent of refugees worldwide experience: The United States selected her for resettlement.

She had a chance at a new life, and to leave the horrors of this one behind. She told herself that resettling didn't mean she was giving up on her children. Hope for the best, fear the worst had become her motto. But her fear had already solidified into grief.

In May 2008, a knock came at the door of Veneranda Mwakasali's modest, four-room house elsewhere in the same province. She heard her father-in-law's voice: "Please open for me," he said.

Veneranda was in the living room, with her 2-week-old baby, Jacques, in her arms. Her other seven kids were already asleep. Her husband pulled open the door to see his father standing in the threshold, crying out; then he stumbled into the house, a knife in his back. A group of militant rebels burst in, stabbing and hacking him, while snatching the family's two most precious commodities, the generator and the television.

In the midst of the robbery, two sleepy figures emerged from doors off the living room: 16-year-old David Baguma, Veneranda's eldest son, and his 14-year-old sister, Angel Baguma. The rebels immediately seized David and Angel, forcing them out of the house and up into the mountains.

The next morning the rebels were gone. So were David and Angel. Veneranda knew that kidnapped young men were usually forced to work for the rebels; when they took girls Angel's age, they often made them into sex slaves. She was devastated but not blindsided: After more than a decade of war, Veneranda had wondered if it was only a matter of time before her family became a statistic of loss. "We only had hope in God," she says. "But we knew that they were maybe no longer alive."

Veneranda, her husband, and their remaining six children left South Kivu and their country by foot. By the time they reached a refugee camp in Uganda, Veneranda believed she was going mad. The shock, trauma and grief of losing David and Angel and watching her father-in-law's murder was all-consuming.

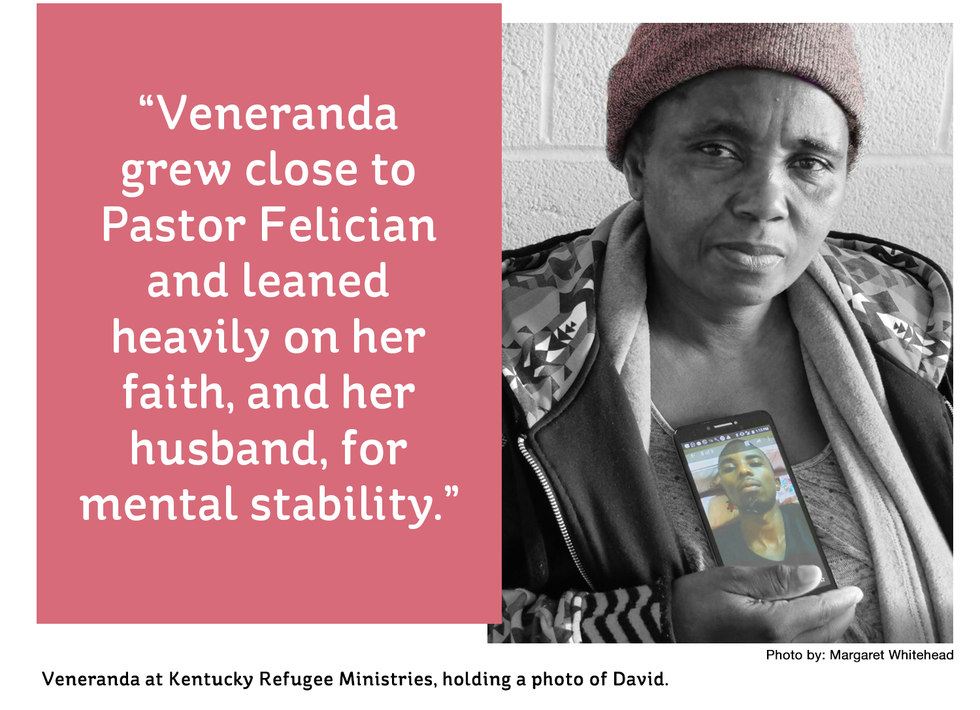

She tried to draw strength from God. Veneranda was a devout Christian and had always turned to church in painful times. She felt physically sick and weighed down with grief, but after two weeks, she threaded her way through the massive, 60,000-person camp to visit the Baptist church. There she met Pastor Felician and confided in him about her missing son and daughter.

Over the next five years, Veneranda became a recognizable fixture within the church. She grew close to Pastor Felician and leaned heavily on her faith, and her husband, for mental stability. Still, pain raged in her knees. She had no appetite but somehow kept gaining weight.

In January 2013, after an offer from the United States for resettlement, Veneranda and her family boarded a plane bound for America.

Later that year, two newcomers, a brother and sister, walked into the Ugandan camp's Baptist church for Sunday service. By the time the siblings met Pastor Felician, he knew exactly who they were.

In America, Veneranda felt like a ghost. Many refugees face crippling mental-health crises once they are finally physically safe, and Veneranda was not exempt. Her resettlement caseworker referred her to therapy, yet the counseling sessions offered no relief. In the dead of night, she'd wake up, wondering, My children — are they alive?

Then, one day, Pastor Felician called. "I think I've seen your children here," he said.

"How do you know?" Veneranda demanded.

"They look exactly like you," he said.

Veneranda couldn't believe it. She had been in that exact camp. What if she had shared the same 70 square miles with her children but never seen them? She insisted on speaking with the boy and girl. Pastor Felician helped arrange a Skype call right away.

When the video chat blinked on and a pair of faces appeared, Veneranda instantly recognized her eldest son: handsome and round-faced, with dark, gentle eyes. And there was Angel, with her angular features and wide, brown gaze.

"Wow, Mom!" David grinned into the camera. "Is that you? Really?"

Veneranda could not stop smiling. Laughter bubbled up from her chest.

Two days after seeing Rehema's brother's photograph, Jacqueline clutched the phone in her hand. Rehema's brother had set up a call with the girl in the photo. He didn't know what it was about; Jacqueline didn't want to tell anyone, just in case her suspicions were incorrect. "Do you know who is speaking to you?" she asked.

"I have no idea," said the girl on the other end.

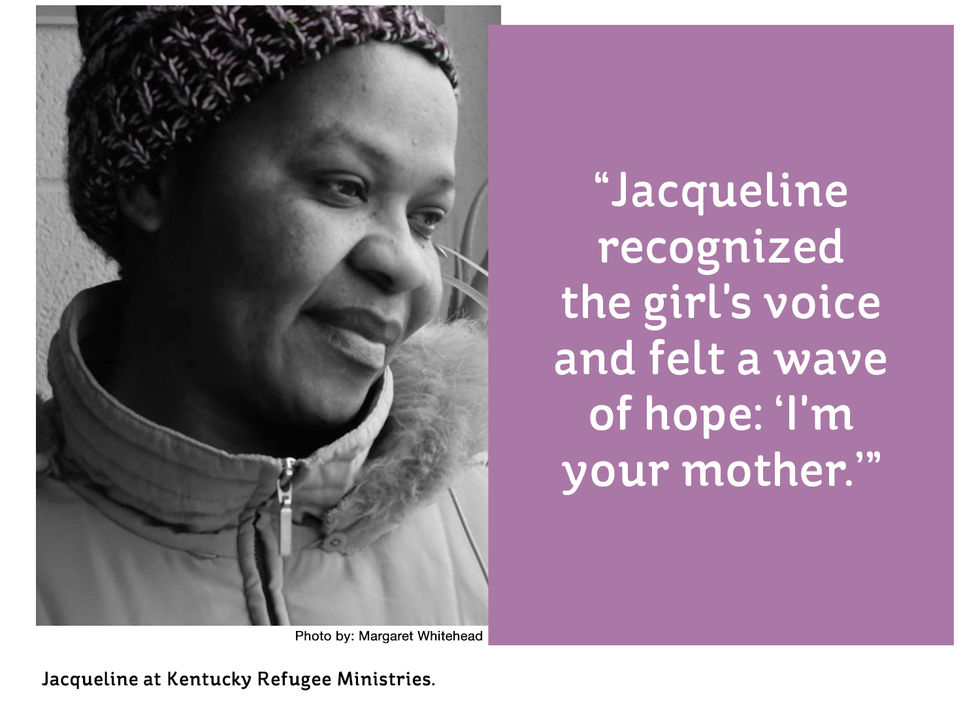

Jacqueline recognized the girl's voice and felt a wave of hope: "I'm your mother."

"Really?" the girl sounded skeptical. Then excited: "Really?"

Ponga insisted Jacqueline recite the names of all of her children. Jacqueline listed them: Nancy, 9 years old the last time she had seen her; then Patrick; Alles; Merveilles, whom they always called Merve; and the youngest, Berthe. When Ponga was satisfied, she told Jacqueline that all five of her younger siblings were alive, too.

Jacqueline's mind surged with excitement. She wanted to keep peppering Ponga with questions, to be sure this was really her daughter. She'd never thought it might happen — her daughter on the other end of the phone, her children alive. A crushing weight dissipated; it felt like "something was lifting off my chest," she says.

That week, she made an appointment to meet with Kentucky Refugee Ministries' immigration lawyer, Emily Jones. Since Jacqueline's children in Uganda were unmarried and under 21, they were eligible for derivative refugee status and a follow-to-join visa to reunite with their mother in the United States permanently. Jones helped her file a petition for reunification.

But the kids' foster parents in the Ugandan camp were skeptical of Jacqueline's sudden maternity claim. So was the U.S. government. Jacqueline would need to pay for DNA testing for herself and the five children she wanted to bring to Kentucky — a $1,600 fee to prove they were really her children. She'd finally gotten a job, cleaning student dorms at the University of Kentucky for $12 an hour, but it was only part time. She explained her situation to her supervisor, who promoted Jacqueline to full time and increased her pay to $13 an hour.

It took Jacqueline six months to earn enough money to pay for the DNA tests. In early December 2016, she received a letter from the U.S. government saying her children were officially approved.

She felt an emotion she hadn't felt in years: joy. In the following days, her thoughts trailed away from practicalities, like enrolling the kids in school or all of the money she would need to support them, to the one thing she kept daring to imagine: "Just seeing them, after such a long time," she says. "My prayers were answered. Just to know they are there — it had a huge impact. I found some mental stability somehow."

Once Veneranda knew David and Angel were alive, she filed a reunification application for them to join her, her husband, and her other children. She told everyone they were coming. She even announced that she didn't need her therapists anymore.

In late 2014, her family moved to Lexington, Kentucky, and she soon turned up in Jones's office. Her previous petition for David and Angel to join her had been lost in the mail, so Jones helped her file a new one. Veneranda marveled at the images of David and Angel that arrived from Uganda: "They had grown up already," she says. "I was so glad and happy."

David's and Angel's cases were approved on October 6, 2015. It took a year for the U.S. embassy in Uganda to process their paperwork, background checks, interviews, and medical clearances, but by January 2017, they had seats on a plane heading to the U.S. in early February.

Then, just as quickly as their plans came together, the new U.S. president took office and declared a 120-day ban on refugee arrivals. In Kampala, David and Angel were glued to the American news. After all this time, Veneranda and her children were once again uncertain if they'd reunite as a family.

But in early February, U.S. judges blocked the ban, and on February 17, Veneranda donned a full ensemble of cotton-candy pink to wait for her long-lost children at the Blue Grass Airport. Emily Jones was there, too, and a news crew from local ABC 36.

David remembers the chill in the airport air. He felt cold and shy. He and Angel came down the escalator, carrying their bags.

Veneranda rushed at them at the foot of the escalator, practically obstructing the other foot traffic. She grabbed Angel in her left arm and David in her right and plunged her head between them, crying out excitedly. Each time one of them escaped her arms she engulfed them again in a hug. She could not stop touching her children.

On a rainy Saturday in April 2017, Jacqueline sits on her sofa in Lexington. On weekend mornings, she gets to call her children in Uganda and hear their voices. But it's the middle of the night where they are, and their distance feels acute.

She still works cleaning the dorms at the University of Kentucky and sends $120 every two weeks to her children through MoneyGram. There is no money left over for savings. Her W-2 accidentally reported that she has six children to support — but those children are not in the United States. The mistake cost her $900 in taxes.

This kind of limbo permeates Jacqueline's life. She is blessedly still a mother. She has children who need her. And yet she has no children — at least not here. Sometimes the stress of the distance chews at her, and she feels helpless in the face of the United States' flip-flopping policies on refugee arrivals. Her children heard about the first refugee ban in January and called her, afraid; Ponga asked if she would ever see her again. Jacqueline tried to comfort them, but all she can do is wait while her children work their way through the immigration system's elaborate maze of background checks, medical screenings and visa processing.

On Sundays, Jacqueline goes to church. She has faith, too, in Jones, who she says both fights for her and comforts her when things get dark. "Right now, I'm feeling good to know that my children are alive," she says. "I'm still struggling to work hard for them. And I still believe in the hope that I'm going to see them one day. That's what keeps me going."

On that same April Saturday, Veneranda, a mid-height, stout woman with petite features, proudly cooks mandazi — bready doughnuts popular in East African countries — in anticipation of a visit from Angel and David, who share a separate apartment. One of her daughters is out for the night at high-school prom and left wearing a grand tulle-enforced dress. Jacques, now six, is glued to a robot-themed computer game.

"I feel like I am back from the dead," Veneranda says. She claims her whole body feels different: "I feel strong." She has no more nightmares. Her mind feels stable. The stress is gone. She credits the change to knowing that her children are coming to her house. "I go to work and come home and cook mandazi because I know they like that."

When her children show up, they get comfortable in the living room while Veneranda wields hot grease and dough in the kitchen. Angel muses that she would like to learn how to cook mandazi, and David suggests searching YouTube for a how-to video.

Angel laughs. She says she would rather learn it from her mother.