'I've never worked on a show I've been this emotionally invested in' says 37-year-old Tate curator Zoe Whitely.

Originally from Washington, Whitely came to London for her MA before landing a curator job at the V&A. One of her first projects, Uncomfortable Truths, was an exhibition commemorating the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade, and the first time contemporary African American art was shown at the V&A.

Now continuing her pioneering work at the Tate, one of this year's most important retrospectives, Soul of a Nation features over 150 works, most of which have never been shown in the UK before. The exhibition asks, 'What did it mean to be a Black artist in the USA during the Civil Rights movement and the birth of black power?'

From the emergence of black feminism, to the way street activism manifested itself in posters and newspapers, to images of iconic figures such as Angela Davis and Muhammad Ali, gives an in-depth look at Black America during 1963-1968.

Here Zoe tells the story behind some of the exhibition's seminal pieces.

Wadsworth Jarrell, Revolutionary, 1972

'Jarrell was part of Africoba; a group of artists from Chicago who were thinking about how art could serve the black struggle and uplift the community. Incorporating text into the work was an important element, this poster portrait of activist Angela Davis is made out of words like 'beauty' and 'struggle', it's so uplifting, but also politically forward.'

Elizabeth Catlett, Black Unity, 1968

'It's interesting how an image can be read in two different ways. On one side of the sculpture is the black fist of resistance; some would view that and see solidarity, other people would see aggression or something to be afraid of. On the other side of the sculpture you have these faces nestled into it, so there's this defiance but equally this tenderness.'

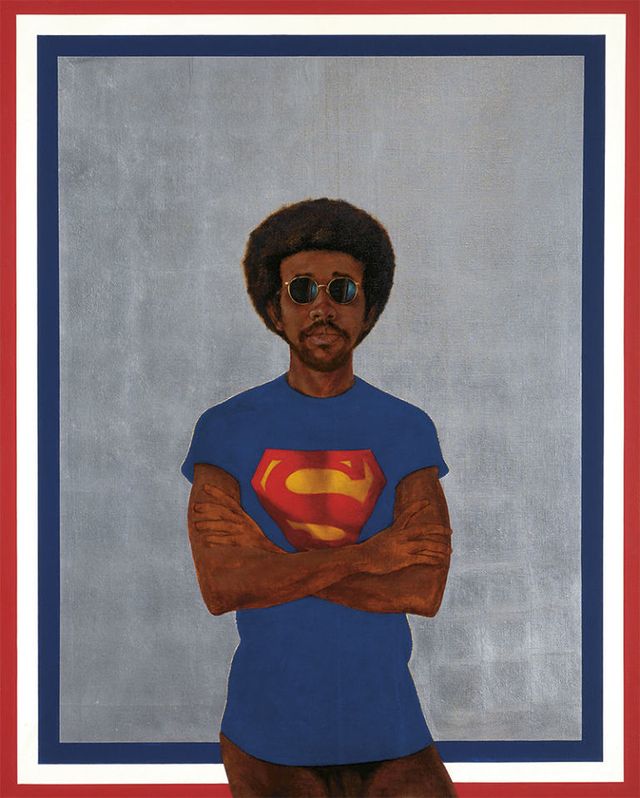

Barkley L. Hendricks , Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People - Bobby Seale), 1969

'The bracketed part of the title is a quote from [Black Panther co-founder] Bobby Seale's trial for conspiracy to incite violence. Because of his outburst in the courtroom, the judge had him bound and gagged, so these shocking images circulated of someone in an American Court of Justice tied to their seat, unable to speak. It's interesting how a statement like that is overlaid with a far more playful approach here. It's a self-portrait, and with that he's painting himself into art history, he becomes the superhero, he's not waiting for anybody else.'

Emma Amos, Eva the Babysitter, 1973

'Amos was part of Spiral Group, a collective of artists that started meeting in 1963 after the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. She was the only woman in the group, and with that emphasis on gender, an image like Eva the Babysitter becomes so poignant. Her daughter is in the picture, and she's made the subject of this work the person who make it possible for her to paint, because childcare is an important issue. We try to address the facets around black feminism, and this painting is a very lovely and uplifting example.'

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power is at the Tate Modern until October 22