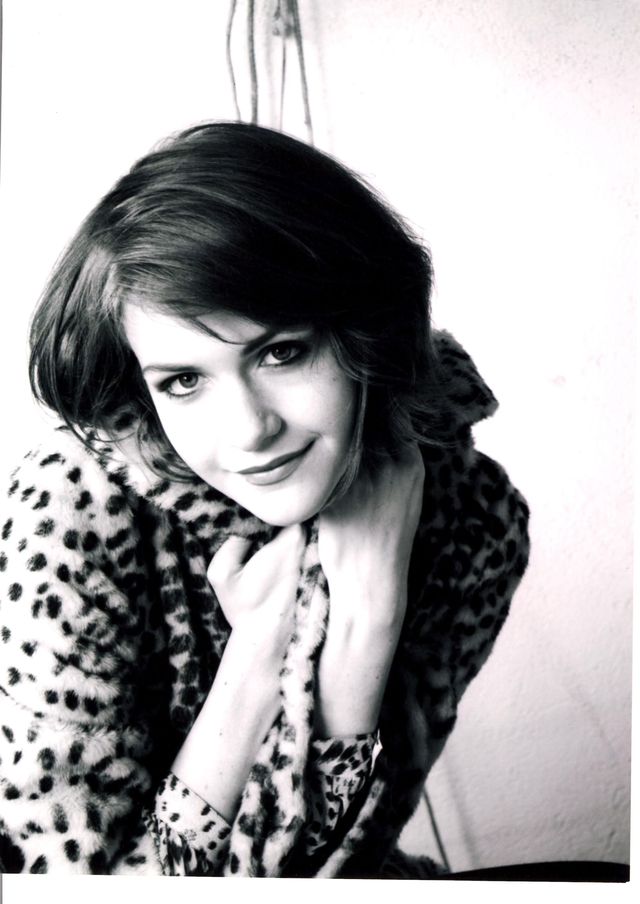

On 1 August 2016, 21-year-old Sophie Reilly was found dead. The evening before, she tragically took her own life at the top of The Dundee Law, an extinct volcano in Scotland.

Growing up in a suburb of Glasgow, Sophie struggled with mental illness for years. Despite battling bulimia, bipolar disorder, alcoholism and spells of psychosis, amongst other things, she eventually gained a place to study St Andrews university, aged 20. But her demons returned and the last year of her life saw her flitting between hospital stays and homelessness, exploring the parks and alleys of Dundee, but also feeling 'freer and happier' than she had as a child.

Sophie might have (at one point) been living on £5 emergency cash a day, but she was also a prolific writer and detailed her experiences with razor-sharp wit, charm and - somewhat surprisingly - humour. In January 216, she chucked her iPhone away ('the best decision I ever made) and instead typed up journal entries from iCafes in the city centre. All of Sophie's writings - poems, drama and prose - have now been compiled into her first book, Tigerish Waters, alongside her journal which was written over the final months of her life (you can read an extract from the book on the Guardian here).

Sophie's brother Samuel, who edited the book, said the collection is a celebration of his sister's truly remarkable voice - both in her despair and soaring euphoria - and hopes it will help other families who are silently struggling with mental illness. ELLE spoke to Sam to find out more.

You're two years older than Sophie. Did you get on as kids?

We were inseparable. Well, until I went to secondary school and we grew up apart a little – as you do as teenagers. But we were always very close.

There's a sweet moment in 'The Joy Of Destitution' where Sophie talks about staying with you for the weekend – she sounds happy. What was your relationship like at that point?

That's a hard question because Sophie was so volatile and up and down and really quite prone to episodes of psychosis. So that weekend, it was lovely to see her, but she was very on edge and difficult. She was obviously not right for a long time, especially in the last couple of months.

I always knew Sophie could write. She was turning out poems from 8-years-old and it was obvious she had a command of language. When Sophie was about 17 she sent me the play that appears at the start of the book. I remember my response so vividly, I said the language was beautiful and there are some amazing moments of dialogue, but I found it extremely difficult to read and my response reflected that.

Why did you find it so difficult?

It was down to the kinds of anxiety I had about Sophie's condition (at the time she'd been diagnosed with bipolar disorder). I remember saying why don't you write about something that's not yourself. I wanted her to turn this gaze, this vision that she had, to the wider world, which seemed like a more deserving target. I was worried about the effect this introspection would have on her condition. Looking back now, that was probably naive.

Telling somebody with these conditions to stop thinking about themselves is possibly the most useless advice you can give. But when Sophie died and I started looking over this stuff again, I was just bowled over by the sheer level of her self-knowledge and self-awareness.

And humour – she's very funny.

Yeah, Sophie was an extremely funny girl. Mental illness is a difficult thing for families and the individual to deal with, it doesn't preclude humour but I think Sophie was funny in her own right.

The book ends on a poignant almost hopeful note – was that on purpose?

As far as I know, the last essay in the book (which is quite upbeat) is the last serious and sustained piece of writing that Sophie did before she died. So it's partly just sheer chance, but throughout her writing there are moments when Sophie is struck by the compassion and aching beauty of the world. Which means at every stage there's a cause for hope. In that sense, the note that it ends on, this poignant optimism, is entirely in keeping with her.

You've also lost a sister. Have you found the process cathartic in anyway?

It was a strange one. I'd go through periods where I couldn't look at it, it was like starting at the sun. Then I'd go through periods where I couldn't do anything else and it was like a complete compulsion.

At one point Sophie writes: 'We are people, not diagnoses' – do we need to improve our attitude towards mental health?

There is an obvious struggle between Sophie expressing herself as an individual and Sophie expressing herself as a product of the conditions that blighted her life. And I think it's probably something a lot of people do feel. The key issue that faces mental health is funding. The number of trained nurses, and doctors, and the availability of hospital and community care, is dwindling and nothing else will fill that gap.

I was deeply annoyed when Jeremy Hunt suggested that one of the ways to cut down teenage suicide rates is by asking social media companies to come down harder on sexting. First and foremost, what Sophie suffered from were medical conditions. It's important to talk about mental illness, and encouraging to see the ways in recent months it's taken a more prominent role in social discourse, but without better funding into research it'll be very hard to make significant progress into what is a very complex and difficult problem.

What would you like people to take away from Tigerish Waters?

I have two hopes for the book: to celebrate Sophie's burgeoning literary talent and that it may provide some kind of point of relation for families and individuals who are going through similar experiences.

Do you think she realised how good she was?

I don't know (laughs). In one of the poems she writes 'I wish I was a poet, But I have no words to give – only sharpness and blades'. And then she ends it with one the most stunningly strange images I've ever read: 'I want my hair to paint my heart.' So there's this extremely assured poetic imagery and this deep anxiety about her ability to convey what she means. But I think most writers feel like that, don't they?

Tigerish Waters: Selected Writings of Sophie Reilly, £6.99, is available on Amazon now; Tigerishwaters.co.uk. Tweet @tigerishwaters. All profits from the book will be donated to the Scottish Association of Mental Health.