Last weekend I visited my mother. I took a bouquet of flowers and a box of chocolates, and drove the 100 miles to her house. I stood outside for 15 minutes, banging on the living room window while she ignored me. One by one, her neighbours came out to silently watch me. The whole time I could see my mother through the window – actually see her – crouching in the stairwell, waiting for me to leave.

I wasn't really expecting the visit to go any differently to be honest. My mother is only in her late sixties, but recently she has turned from an independent, active retiree into a full-blown recluse. Three years ago, for example, such a trip would have been a different story. Three years ago, my mother would have flung the door open, wrapped me in a bear hug and made me coffee. We'd have caught up over far too big a roast lunch for two diminutive women and enjoyed thimblefuls of the fun-size bottles of rosé my mother likes to buy but, mysteriously, refuses to refrigerate. We'd have laughed. We'd have bickered. She'd have told me off for swearing so much in print. I'd have rolled my eyes at her insistence that homeopathy is 'a real science'. Then I'd have said goodbye, something twinging painfully inside me as I saw her retreating frame silhouetted in the porch light, all alone, and I'd have texted her when I got home to let her know I was safe.

But these days things are different. Now she is ill. Now I have a one-year-old son she has yet to acknowledge, a wedding she didn't attend, a husband she has not met. She is ill, I have to keep reminding myself. She doesn't hate me, she is unwell.

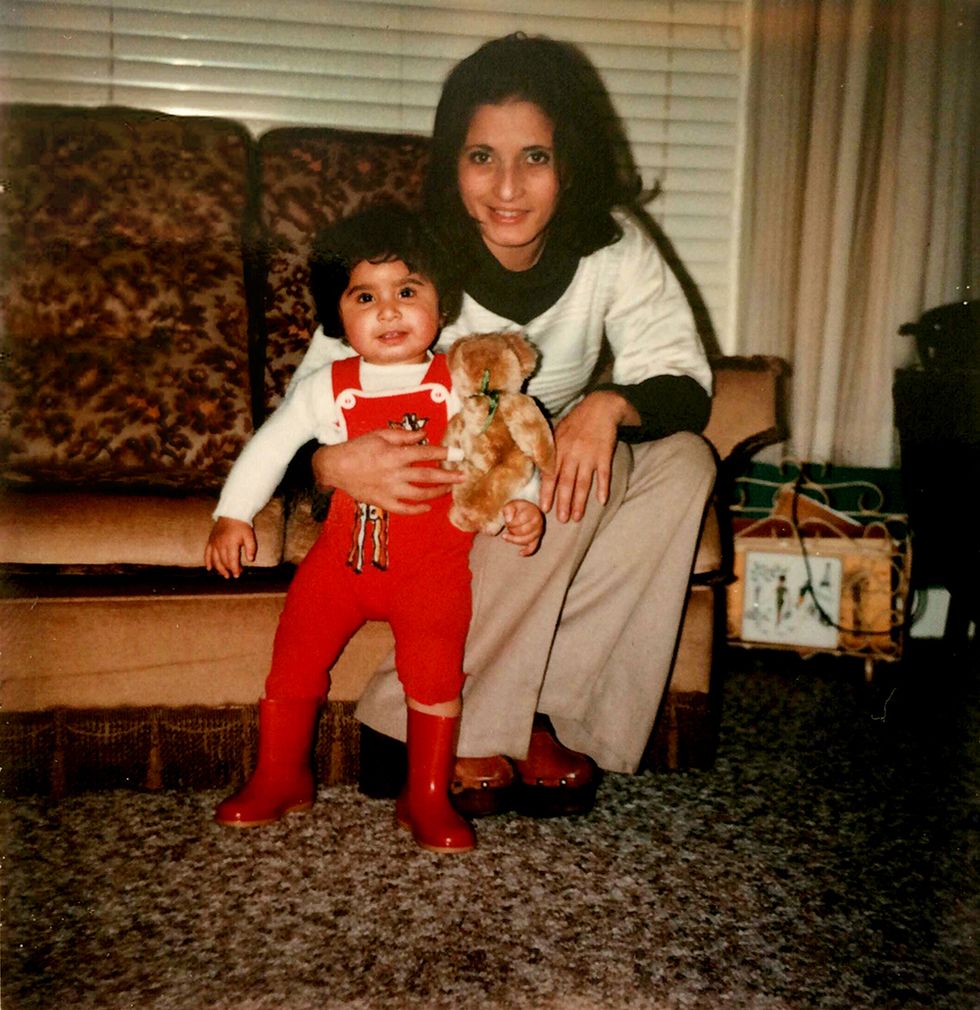

At least, I think she's unwell. The general consensus is that something is wrong but she won't let the doctor in to make a diagnosis. The police get waved away when they visit once a month with a battering ram to find out why she's not answering the phone. The social worker and the local psychiatric team she will not countenance at all, despite the fact that they make a pilgrimage to her door every few months. 'Trespassers!' she yells through the window, and worse, until they leave. 'She seems like she knows what she's saying,' they tell me when I call. Me, she hides from in the stairwell.

To say it hurts is an understatement. It hurts me to see my mother's features playing out across my son's face as he grows. It hurts whenever I see something my mother would enjoy and then realise that I can't share it with her. It is as if she has died, and it makes no sense. My mind is full of question marks when I think of it. This can't be my mother, my brain tells me. My mother loves me. My mother used to let me choose any of the expensive perfumes on her glittering dressing table when I was ill as a child, and she'd use it to scent the water she sponged me down with, to cool my fever. My mother who, when at aged 12 I took to my eyebrows with tweezers and came down the stairs in shame looking like Fanny Cradock, over-plucked her own eyebrows in solidarity. My mother who even nursed me through a breakdown when I was 21. This can't be my mother. It's impossible.

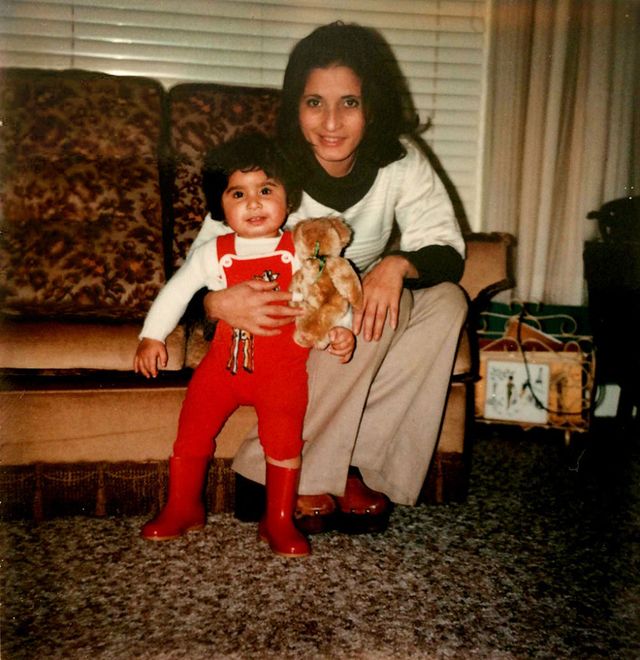

But then my mother has always been impossible. When I was growing up, she was warm, independent and quick to temper. I loved her fiercely. I wanted to be her. She exuded an effortless, European, high-cheekboned sort of beauty – all tumbling waves and dark, heavy-lidded eyes – and I wasn't the only one who noticed. Men were always asking her out and, I swear to god, when she was in her forties and complaining of being frumpy, a passing gentleman did a double-take in a New York hotel lobby and stopped to check that she wasn't actually Sophia Loren.

But she was also a clown, pulling faces and doing silly impressions while dressed to the nines in black and gold. She spoke seven languages, played Spanish guitar and piano to concert level despite having lost 60% of her hearing, and composed beautiful, melancholic poetry. When I was very young, my mother was dreamy and unreal; more like a character in a novel than a person.

This is largely because she wasn't around much. She worked abroad as an interpreter and I spent a lot of time with my grandparents. My formative memories of my mother – blackberry picking on balmy summer afternoons, learning words through sounding out the syllables ('Ichthyosaurus' hasn't been an issue for me since I was three), and learning how to cook Italian food – are all tinged with extra specialness because she was home, and she was choosing to spend her time with me.

I have edited out, as most would, the long depressions she fell into when she surrendered to full-time wife and motherhood. The woolly spiritual quests she went on in order to add meaning to her life. How she seemed to be holding it all together until my father died unexpectedly when I was 10, our once-solid family unit becoming fragmented. We all retreated into our own private grief and then our own private recoveries, and after several years of boarding school I wound up with an estranged brother living abroad and a mother who occasionally had nothing behind her eyes, which terrified me, so I kept trying to please her.

And for the most part, it worked. I ignored the bits that felt wrong about our relationship, like how all opinions that contradicted her own were ignored. Or the fact that, increasingly, no moments were ever allowed to belong to me; not even when my best friend died in an accident.

Or how everything, in the end, had to be about her.

My mother stopped talking to me in 2014. She had suffered a worrying few months of illness (high blood pressure, the doctor said) where she had entirely stopped taking care of herself and, although she had bounced back, our Sunday lunches were becoming bizarre. Long, meandering reminiscing started to replace our postprandial walks by the river, and then the reminiscing would take a turn for the fantastical. She'd reference conversations that never happened, with me or with other people. These conversations were largely upsetting and she was generally the victim.

'Your grandmother was a whore,' she told me one day. 'She was a whore all around town and everyone knew it.' Then she said some worse things, things I can't ever repeat, about my father. About her own father. About everyone I've loved who has gone. Things that cannot possibly be true. 'Are you making this up?' I asked her. She did not meet my eye, and she did not reply.

In 2014 I told my mother, who was growing increasingly reclusive, that I was pregnant. I told her breathlessly in an email. I told her before I even told my husband. She didn't reply for two weeks, and when she did it was a furious tirade. I was selfish, she said, and uncouth. I was callow; I had abandoned her and chosen a new family. She wanted no part of it. She wanted no part of me. And that was that. Well, that should have been that. The truth is it's not so simple. Just because my mother decided I was persona non grata, it didn't mean that I was magically extricated from her life. If my father was alive, or if my brother hadn't distanced himself from the family years ago, or if we weren't so aggressively international that our nearest relative wasn't an aunt in Paris I hadn't seen for years, there would at least be some sort of buffer. I wouldn't wake up at 5am terrified that my mother was dead. The buck wouldn't stop with me.

But it does stop with me. I still pay for my mother's phone, and a chunk of my income is still used to pay off the massive bill I took to help her out during her illness. Every month or so, when the home- help support freak out and become convinced that she's slumped dead behind her front door, it's me they call. Me, 100 miles away. Me, who can't do anything. And every few months they make enough of a noise – and rightly so – to rouse the social services and psychiatric team, and then it's up to me to trot out The Ballad Of My Mother over the phone to them, while bouncing my own son on my knee, before they hare o to her house only to be turned away again.

I go through cycles of emailing her chatty family updates and photos of my son. Sometimes, when the silence of no responses becomes too deafening, I crumple and descend into sadness and anger, and decide that I don't have a mother. But I do have a mother. And she still emails me. She didn't email me when I went into hospital to give birth, but she did email me on my birthday. She didn't reply when I told her I had postnatal depression, but she did send me a two-paragraph update about her hydrangeas.

The question marks in my head are starting to lessen. I'm beginning to see that it's been a long and not entirely surprising journey for her to get where she is now. And that perhaps she wasn't just hiding from me because she didn't want to see me, but because she couldn't.

Whether it's dementia, mental illness, an unnoticed stroke, which is what I suspect has happened, or my mother has just mentally surrendered to the imagined bitterness of life, something is stopping her from engaging with me, and I have to accept that. Living with such uncertainty and so many unanswered questions is hard, but it's what I have to do now.

In a way, last weekend's visit was closure for me. I am going to stop ringing her doctor and her social worker in desperation. Of course I miss her, and I could do with a mother. But in a way my mother has raised me to be strong enough to survive and thrive without one. It's a hard pill to swallow, but it's not up to me to fix her. Especially when she has made it so clear that she doesn't want me in her life.

In the end, I left the spring bouquet and the box of chocolates on my mother's doorstep along with a card. The card read, 'To ma, I love you. Love Robyn'. I meant it. I also walked away, and I meant that, too.