Reni Eddo-Lodge is the 28-year-old writer who, by deciding not to talk to white people about race, has found herself talking to a whole load of white people about race.

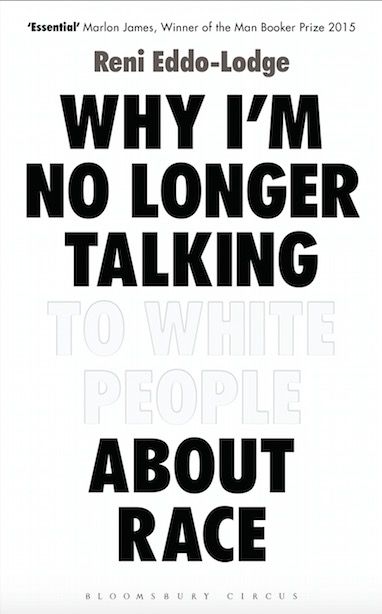

In 2014, Lodge wrote a blog post titled Why I'm No Longer Talking To White People About Race. She was 24 at the time, but it's an arresting and mature piece of writing, filled with eye-opening nuance you might not expect from the fairly belligerent-sounding title.

And it caught the interest of many, Reni told me over a coffee at the London Review Bookshop.

'[That piece] took on a life of its own,' she explains.

'It strongly resonated with people in a way that I didn't anticipate. I learnt that a lot of people, who incidentally weren't white, were feeling the same. But they were scared to talk about it because they were worried about being monsters.'

Alongside the overwhelming response, it also landed the self-confessed 'scrappy freelancer' a New Yorker commission, which in turn, provided her with the opportunity to write a book titled the same as the blog post. As she puts it: 'I knew that there was nothing else I could write'.

Now garnering attention from the likes of last year's Man Booker Prize winner Marlon James (author of A Brief History of Seven Killings) and the editor of The Good Immigrant Nikesh Shukla - Reni is the toast of the town.

'So many prominent writers of colour have told me that this was they book they have wanted to write', she explains. That this book was fifty years in the making for some of them - so how come Reni was the one to do it?

'I think this is the huge benefit of starting as a graduate. Someone said to me the other day, "you're so brave", when I started writing I had literally nothing to lose, no job, never had any money to pay the rent, no family, no mortgage, nothing, nothing to lose, no social position to be concerned about.'

Being carted out as the token black feminist in 'low level media bits' came to a head in an incident on Women's Hour when Caroline Criado-Perez took offense to Reni's suggestion of a lack intersectionality in feminism in 2013.

Four years later, Reni can't help but laugh.

'So the conversation quickly moved on from why structured racism is endemic in our society to Caroline's being bullied by people on the internet.

'I included this story in the book. I think it's a really good example of utter cluelessness.

'Why does it have to be about you? I found myself at the end of a lot of hostility from white women who worked in journalism, media and publishing, who were perhaps even twice my age who said I was a bully. I was pinpointed as the problem.

'No wonder feminism is so white. I think things have got a lot better since then but I was basically hounded out of the room.'

Talking to Reni, she pulls no punches saying 'white women.' She does not say 'some' or 'can', she just says white women.

She also laughs a lot, and warns me at the beginning of the interview she finds it difficult not to ask questions back. And once the dictaphone is off she does just that, her journalistic impulse bubbling to the surface.

Talking to Reni is a similar experience to reading her book: honest, opinionated and pretty kick-ass.

What is the big misconception you are trying to address with this book?

For so long we have understood racism to be about interpersonal nastiness and spitting at people in the street. It can certainly manifest like that but I was trying to talk about something much broader about our systemic problem.

When I was trying to talk about it I was coming up against white people who were like: 'well I'm not a racist, how could you say such a thing, I haven't got a racist bone in my body', and immediately shut down the conversation.

I thought what was really useful about this book was that you define your terms and lay down some jargonistic words that are somewhat overused and can often feel like they have lost their meaning. Things like defining racism as prejudice plus power, or breaking down how systemic racism works.

I knew that those sorts of definitions help me.

Again and again the information I gathered showed that if you're not white, particularly if you are black, you are more likely to be held back by institutions that should be treating us all equally.

A black boy is twice as likely than his white classmate to be excluded from school. By the time it gets to Year Six, children of colour are systematically marked down by their own teachers when it comes to SATs exams.

African American sounding names are less likely to get called to interviews than white sounding names.

We all need a job, we all need to go to school, we all need to come into contact with the NHS.

So we're seeing this racial bias again and again.

The point that I make in the book is while we know that people who are staffing these things are not KKK members, we're still seeing that systemic bias.

So it's not as simple as 'I don't have a racist bone in my body', clearly there is a broader framework that contributes to this.

Racism being prejudice plus power is something that I came across at university. But I realised that so many other people did not have the starting point, which is why I had to write it down.

It's the power to negatively influence other people's live. I use an anecdote in the book: I went to go and get myself a nice delicious meal of Caribbean food and the man behind the counter said: 'I'm gonna give you the best cut of meat and not those people' (they were white). That's prejudice, but all he has power over is their lunch.

Exactly, and that's why interracial families or 'having black friends' isn't 'solving racism'.

Absolutely. When I was growing up my mum always said to me you have to work twice as hard as your white counterparts. But I've learnt from my white friends that when they were growing up they were being told everyone is equal.

There are two different conversations going on there.

White people are told let's be colour blind and never raise race.

Yes, we're living closer to each other than ever before and we are recognizing the humanity in each other, but still systemic racism exists, still racial stereotypes exist.

That's a terrible situation. There's a white blind spot when it comes to these issues.

Throughout history I think women have been sold a lie that white women actually extend their hand across the boundary of race to help other women. We know that isn't true, something like 62% of white women in the US voted for Trump.

I think white women, particularly those that are feminist, think 'I've got my progressive badge on, I'm fighting for the patriarchy'. And then that's it.

They are not thinking about where they benefit from the system. There's this image on Twitter at the moment, basically screenshots from Oprah's magazine, O.

There are some where every single woman servicing other women are white and all the women getting their nails done are Asian.

Women are not aware of how women of colour are basically set up to serve women in different ways and seeing the world through their eyes and standards of beauty, white woman standards of beauty. White women just don't know or don't care or don't recognize that to be an issue.

We've been talking a lot at ELLE about tokenism. Though we have a fairly diverse team, we want to get diversity, and representation, in the magazine without tokenism. What would you suggest to women's magazines about how to navigate that?

My question is who is setting the agenda?

I think the feminist movement that I was involved in, and I don't consider myself part of it anymore, was very interested in having women of colour at the table if you just assimilate to whatever they want to do.

But they don't want you to challenge the agenda. It's a bit whitewashed, then it becomes very hostile very quickly.

So who is setting the agenda? That's the place to start.

Recently there has been an increased consciousness or a demand in consciousness regarding the worse parts of British history, like issues with the Commonwealth and Empire, as well as our role in the Slave Trade. You talk about this in the book.

Other countries are much more up front about the bad stuff they've done. It's really not something that we know about.

When I was in school, I learnt black history about Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King Jr. And I didn't learn that around the same time of the 'I Have A Dream' speech - a literal Rosa Parks situation was happening in Bristol where there was a boycott of the bus service because they wouldn't hire black people.

Think about the legacy of that. That was in the 60s. Black and brown people have been cut out of this country's wealth, yet we're instrumental in building it in both consensual ways and nonconsensual ways.

We are seeing a rise in racism online in the wake of the Manchester Arena attacks, what do you think about that?

I used to live really near the area and I have family there who have teenage girls, so it's all very jarring.

I don't like looking at social media because people treat these sorts of things too lightly and argue with each other and bicker on social media. I find it so distressing and distasteful.

I talk in the book about anti-racism in the wake of the terror attack in Paris of 2015. When everybody was mourning, some people who I think would call themselves anti-racists, were like 'oh we never really mourn in this way when terrorist attacks happen to black and brown countries'.

Okay fair point, but can you just wait five days, can you wait till the bodies are cold?

I check in on my friends and family, then I just log out and take care of my house plants, go for a walk, listen to a podcast. You've got to look after yourself.

Do you think that social media can make progressive, political change?

I do think the internet is very good for awareness raising about general injustices.

But then it's like, okay what do you do next?

I used to chat on social media about how bad things are and then I asked myself if it was beneficial. Am I just looking at social media everyday to find more bad news to share?

So I decided that I needed to find a different way of being a good contributor to changing things, which is a reason why I wrote the book. I'm a big person for channeling anger into some creative endeavor.

What would be your advice for an ELLE reader to be more engaged?

My big thing is to find a support network.

I wouldn't want to be too prescriptive and I don't know who is most influential to you in your life. I think that's something that each person has to determine by themselves.

Your aunty will probably just leave an angry comment under an article I write, but she might listen a little bit more if you tell her.

Daisy Murray is the Digital Fashion Editor at ELLE UK, spotlighting emerging designers, sustainable shopping, and celebrity style. Since joining in 2016 as an editorial intern, Daisy has run the gamut of fashion journalism - interviewing Molly Goddard backstage at London Fashion Week, investigating the power of androgynous dressing and celebrating the joys of vintage shopping.