TANGAIL, Bangladesh – A man screams, and blood is drawn. Several hundred women emerge from their bedrooms, stumbling into the street. Eager-eyed, they stand on tip-toes and sharpen their elbows to get a better look.

Somewhere through the knot of angles and limbs an elderly woman in a mustard-coloured saree can be seen – can be heard – swearing, as she drags a man almost twice her size down a concrete alleyway by the torn collar of his t-shirt.

Behind the pair follow three teenage girls in Western pyjamas and skinny jeans, hissing and jeering and waggling nails filed to a point. The man turns a freshly scratched cheek to spit at their feet – and a chorus of silver bangles jingle in unison as the 16 year olds' friends pull them back by their waistbands and they rain tight-knuckled blows against a wall of air.

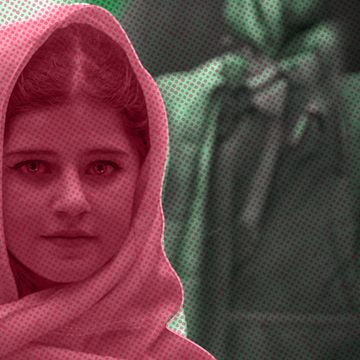

The girls aren't playing by the rules. They're supposed to be sitting on upturned laundry buckets outside one of the eight official entryways to the brothel, faces bleached white with Gopinath's 'panc–cake' powder. Their job is to lure customers into the brightly-painted labyrinth of moonshine and ganja smoke, where ten minutes of sex sells for 200 Taka [£1.80] and women are in control – albeit often of one another. But it's August, and the prospect of another hour spent in the choking humidity of the South Asian summer sun isn't tempting. Plus, the man didn't pay.

Dating back 200 years, Kandipara is the oldest brothel in Bangladesh: a self-sufficient maze of windowless bedrooms, tea shops, roti stalls and drunken tailors. On a good day, its 400 employees will see 11 customers each, 'or maybe 12', they say, expressions sketched in contrasting shades of hope and dread. Either way, morning shifts start at approximately nine o'clock as businessmen and students from Tangail begin their rickshaw commutes to the office with a quick stop-off to stock up on sex and cigarettes. Then a steady stream of taxi drivers, shopkeepers and labourers find excuses to drop in throughout the afternoon.

But today doesn't appear to be a good day. At least the drama serves as a distraction.

Moyna doesn't like the chaos. One of the brothel maids is squatting on the floor preparing lunch on a small stove, and the 19-year-old can smell turmeric simmering next to garlic and bay. It's tempting to give up; to curl up on the wipe clean tablecloth that covers her bed during work hours and retreat. But her neighbour, Kajol, has fixed her with a watchful gaze, so Moyna stands firm in the corridor.

She's only been at Kandipara for a fortnight, after catching a bus from Bangladesh's largest and most notorious brothel in Daulatdia, where she was trapped for five years. She turned up at Kandipara and nervously asked to rent a room. After half a decade in the sex industry, she figured finding a smaller, safer brothel was the best she could hope for - but now, as a freelancer, she needs to prove herself. Leaving Daulatdia, and the madam who imprisoned her there, took courage. The curry can wait.

'Everyone sounds angry in brothels all the time anyway,' she says, combing almond oil through her hair. 'Most of the time, everyone is.' There's a pause. 'I think we have a lot to be angry about.'

Her words are weighted and precise. She has little interest in her colleagues who lose control and fight back against their customers. 'But I understand. When I first started working, I wanted to kick and bite and hurt every man who came into my bedroom like I was a dog. I begged them to leave me alone, but they wouldn't stop.'

She was 13, and nobody had ever told her what a brothel was.

'I didn't understand what I'd done wrong, and why none of the older women would let me leave.' After a few weeks passed, she stopped asking. 'My life was already ruined. I figured I should do what they told me.'

The only Muslim country in the world where sex work is legal, it's estimated that there are over 20 'brothel villages' dotted across Bangladesh, with up to 10,000 employees split between them. There's one rule, but it's consistent: every sex worker must be in possession of a police-issued certificate declaring she's there willingly, and that she's over 18. How she gets it - how she gets to the brothel in the first place - is a question few seem to want to ask.

Moyna didn't come willingly, and she wasn't 18. Like thousands of girls in Bangladesh, she had been brought to the brothel by her husband, who sold her for 300,000 taka [£2700] without her knowledge or consent. 'I never found out why,' she says. 'I guess that's all I was worth.'

Everything had been normal until she turned 11, she says. An only child raised in rural Ishwardi, a railway town 200km to the west of Dhaka, her days were structured around school and play. The former was mostly spent sliding notes under the desks to her five best friends. But the latter featured daily games of hide and seek with her cousins who lived next door. Small for her age, Moyna's trick was to hide in between the roots of the trees next to the riverbank, curling her body up into a ball so the boys wouldn't spot her in the shadows. Somehow her 15 year old cousin, Monir, still always managed to find her first.

That day, she'd skipped the game. Her grandmother had told her to hurry home. 'I was excited, I thought there was going to be good news,' she remembers. 'But she placed a hand on my shoulder and told me, "next week, you're going to marry Monir. Everything has been arranged."' Confused, Moyna went to try and play with her friend and soon-to-be husband, but he told her to go away. It was no longer appropriate. 'We have to be grown ups now, he said.'

The legal age limit for marriage in Bangladesh was 18, and Moyna's teachers warned her parents that their daughter was too young. 'But my parents explained that they had no choice. I was too expensive. So my teachers relented and said they'd attend the ceremony too.'

Unfortunately, that's not unusual, says Salma Ali, former Executive Director of the Bangladesh National Women Lawyers' Association, explaining that Bangladesh has the fourth highest rate of child marriage internationally, and - at 22 per cent - the highest rate of marriage involving girls under the age of 15 in the world. And it may get worse. The Child Marriage Restraint Act 2017 included a loophole where a court could allow underage marriage in 'special cases' – without defining the term. Women's Rights campaigners argued that what little protection remained for Bangladeshi girls was effectively removed overnight. Moyna nods. 'When I told my Granny I was scared of marrying Monir, she hugged me and told me that I was a girl, and that this is just what girls have to do.'

There were other things girls had to do too, Moyna discovered. A year after the ceremony - seven months after her periods began – the 12-year-old started vomiting in the kitchen, on the floor. Her grandmother told her 'the baby comes out the way it went in', and she nearly vomited again. 'When I went to the hospital, they told me I was too small to give birth normally, so they performed a Caesarean. I was so young, I didn't understand what was happening until they handed me my daughter.' She named her Kaya, meaning "flower."

Meanwhile Monir had started disappearing for months at a time, coming home with a wallet full of brightly coloured wads of cash. One day he announced he was taking Moyna to Daulatdia, a town 100km to the east, so they could spend time together away from the baby. On board the train, she sat crushed between her husband and a stranger. The motion made her feel like she was flying and falling at the same time and there was a feeling in the pit of her stomach 'telling me that something was terribly wrong.'

When they disembarked in the darkness, Monir picked up her suitcase and led her along the railway track to a bare tin room with a single bed. 'We'll stay here tonight,' he said, before telling her to get some rest while he went to buy food. 'I sat and waited for him for thirty minutes, maybe an hour… eventually I must have fallen asleep.' When she awoke, it was morning. Monir still hadn't returned. 'I went outside and asked a woman sitting on the floor if she'd seen him. She started laughing, and just said, "Oh him? He's gone. He sold you to me last night."'

Moyna's voice catches at the memory, and she stands up, tearful, to leave the room. A middle-aged man is leaning against the wall in lungi – a traditional Bangladeshi man's skirt – paired with a too-short polo shirt that shows the white curly hairs of his stomach. He reeks of locally fermented alcohol and stale cigarettes. On spotting him, Moyna stops, and begins negotiating her price.

Kajol is concerned about her neighbour. The 28-year-old has been watching Moyna since her arrival, and she wants to help. 'The girls who are sold by their husbands are the ones who suffer most, because they've been betrayed by the people they tried to love,' she says. 'I don't know how many girls here are former child brides, but it must be lots.' She herself was married at 12, and ended up at Kandipara after her husband abused her and she fled – into the arms of a trafficker. It's taken 13 years to buy her freedom, and now she's not sure where to go. 'We are all tortured here. I wish places like this didn't exist.'

'When I first arrived at Daulatdia, running away wasn't an option,' explains Moyna. 'I was locked up, and I didn't have a mobile phone. I didn't know where I was, or how to get back to where I came from.' She didn't know who to ask for help. 'Who would believe me? The police come to the brothels as customers. What would they do?' The woman who bought her expected Moyna to earn her freedom, increasing her debt weekly to account for food, rent and electricity. 'If you didn't earn enough money, then you were beaten,' she explains. She was sent her first customer on her first afternoon. 'After that, the shame keeps you in place,' she says.

These days, when she calls her grandmother on a borrowed phone, she weaves elaborate tales of garment factories in Dhaka and busy city streets. She's told her family she's separated from Monir, but she won't tell them why. If they learned she was selling her body, she knows they would disown her on the spot. Better to let her parents believe she's so successful she just doesn't want to return. 'How do you tell your daughter her mother is a…' A tear falls down Moyna's cheek. 'It's just better for me to stay here, I think.'

Local NGOs, including Rights Jessore, the Bangladesh National Women Lawyers' Association and BASHA Enterprises, understand the difficulty in getting women out of brothels. They're working tirelessly to provide sex workers with alternative vocational training, currently accommodating over 100 women in secret shelters across the country. But after years of abuse, thousands more sex workers are too deeply traumatised to leave: the stigma of what they've experienced is too strong. In Daulatdia brothel alone, there are thought to be approximately 3500 working women - and there's no accurate means of calculating how many are under 18.

'Legal organisations have to be the ones organising the raids,' explains Robin Seyfert, Founder of BASHA - a social enterprise that provides trafficked women with support, education and full time employment after they have escaped.

'But there are still a huge number of girls who urgently need rescuing. Regardless of whether they're too scared to leave or physically trapped, they can't just walk out of the brothel and ask for help.'

The raids themselves are dramatic, and see male NGO employees sneak in undercover, posing as customers to scout out the environment and look for underage girls who might be suffering particular abuse. Once identified, female staff members and senior police storm in together - physically breaking down bedroom doors and pulling the sex workers to safety; fighting off screeching madams who maintain the girls are old enough to work legally and have debts to repay.

'By the time the women reach us, they're often terrified. The skills that may have helped them to survive in the brothels - such as violence, defiance or possessiveness - are not necessarily the skills that help them to integrate into society or a workplace. So it takes a lot of time and patience to help them overcome that.'

'I think it's too late for me,' Moyna says, when faced with the idea of leaving brothel life for good. "My life is already over. I should focus on earning as much money as possible for my daughter's future, so she never has to live through this.'

But sometimes, even on her darkest days, hope still sneaks through the shadows and the teenager waivers; blocking out the brothel corridors with brave, dreamy plans to pack her suitcase and go home. After waiting to make sure Monir is out of the house, she'll grab her daughter from her husband's family, and the pair will run away, buy a plot of land and a couple of buffalo. 'Then I'll pay for Kaya to go to school until she's 18, and we'll live a happy, simple life together,' she says. 'We won't need anything except each other.'

In a way, perhaps leaving her madam in Daulatdia and finding independence in Kandipara was just the first step.

Translation by Pragna Chakma. Additional reporting by Ali Ahsan. Reporting was supported by Girls Not Brides.

'The Warriors' is a year-long reporting project by ELLE and the Fuller Project for International Reporting, funded by the European Journalism Centre via its Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme.