When they were younger, before their son was born, Maria's boyfriend started hurting her. He would place his hands on her neck and squeeze tightly until her skin turned pink and she gasped for air.

After her son Andrei came along, the abuse got worse, and her arms were regularly crowded with bruises, her face sore and swollen.

Maria had no clue Russia had softened the penalty for domestic violence. Her partner, however, was all too aware when the bill sailed through government last February.

'He heard it on the radio. He told me, "Now I can hit you by law,"' she says, her voice wavering. 'I was horribly scared, but he thought it was funny.'

We are talking in the kitchen of 'Aistyonok', or Little Stork, the shelter where Maria stays with Andrei. Run by a women-led Russian charity, the refuge cares for women and their children fleeing violence.

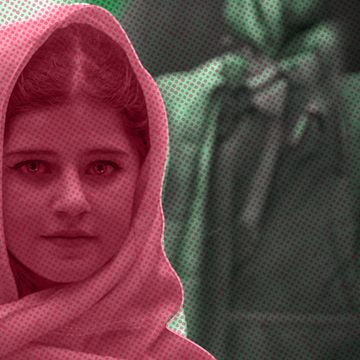

Maria, 35, is soft-faced with poker straight black hair past her shoulders and wide, high cheekbones. Her pale grey eyes cloud over in memory as she recalls life with her partner of twelve years in Yekaterinburg, a large Russian city in the Ural mountains that straddles Europe and Asia. He was a heavy drinker, and would go on benders lasting days. When she went to work, she left Andrei, who is now three, with him at home and would worry he could injure him, too. 'If I didn't leave when I did, he would have killed me,' she says.

Reaching the refuge for battered women, where she has lived since August, was a journey riddled with hurdles. Maria and Andrei (not their real names) stayed with her alcoholic father, whose drinking 'was no better than the man we were running from,' she says. At first, he took an interest in their plight, but this soon turned to blame, at Maria, for being 'so weak' as to allow herself to get beaten, kicked, spat on and cursed at, every week since Andrei's birth.

The mother and son then decamped to her cousin's place, sharing a bed in the corner of the small kitchen of their flat. Her cousin's husband, disinterested by the ordeal, later relegated them to the balcony. Andrei, perched beside her on a chair, listens as he slurps lukewarm black tea from a mug, heaped with sugar. His eyes widen at the name of his father.

Such stories in Russia are now increasing in number, almost a year after domestic violence was reclassified from a criminal to an administrative offence. Under new legislation, abusers can avoid jail time, and instead pay a £375 fine, if the beatings occur – or are reported to occur – not more than once a year, and if the victim has suffered no lasting harm, such as a broken bone or concussion. Pulling out hair, or causing skin to break and need stitches, or skin to discolour, turning into a patchwork of purple and blue, no longer qualify for time behind bars under the new bill.

Russia already has a serious domestic violence problem: at least 12,000 women are thought to be killed each year at the hands of their abusers, mostly male partners, according to Human Rights Watch. That is roughly one woman every forty minutes. And those are just official numbers; much abuse goes unreported. As if that weren't bad enough, women are often sent back to their abusers when they go to the police. And those are the women who have mustered the courage to seek help.

In response to this epidemic of violence, only made worse by the government, there are the Russian women championing change in the other direction. A week after the bill went into effect, around eighty people staged a protest in Moscow, in the fenced-off corner of a Moscow park. Under a soft snowfall, women held up signs with common Russian proverbs endorsing abuse against women. 'Hit a woman with a hammer, and she turns gold,' one read, which roughly means if you hit her, she becomes more worthy. 'If he beats you, he loves you,' went another.

Shivering to one side stood the prominent Armenian-Russian lawyer Mari Davtyan, who defends female victims of abuse across the country. 'We will fight until domestic violence becomes a crime,' she said.

Davtyan is part of a small cohort of Russian women who have designed a far-reaching, clear-cut law they hope will convince the Russian government to reverse the changes. Their law also includes the introduction of restraining orders, currently lacking from Russian legislation.

The country does not have a specific law targeting domestic violence, meaning partners and children abused in the home are categorised under the more general crime of assault, even though they are considered more vulnerable. Activists were given hope in the summer of 2016, when the Russian parliament decriminalised assault but omitted domestic abuse, leading Davtyan and other lawyers to believe Russia was about to turn a corner. But after outcry from the church and its backers in parliament, the February legislation reversed the move. Davtyan remains cautiously optimistic. 'Every day, I meet women with broken lives and health,' she said. 'We will continue the struggle.'

President Vladimir Putin signed off on the decriminalisation of domestic abuse days after parliament overwhelmingly voted in its favour. That same morning, Russia's air force tested for war readiness, under instruction from Putin. Some say the two events are not unconnected, a macho show of force for a resurgent Russia courting traditionalism. And leading this wave of conservatism is Russia's powerful Orthodox Church, which is enjoying a meteoric rise more than a quarter of a century after the fall of the atheist Soviet Union.

Perhaps the most dominant player in rolling back women's rights, the church has called efforts to severely punish domestic violence abusers 'satanic' and 'against Russian culture.'

Modern Russia often feels in the midst of an identity crisis: today, over 70 per cent of Russians identify as Orthodox, up from just over a third in 1991, according to a major Pew Research Center study last year. And though church and state notionally are separate, an ever-strengthening alliance exists between Putin and the Russian Orthodox faith. In cultivating an image of a strong and unified Russia, the Russian president has encouraged the church to make serious forays into Russian society. And where they can, prominent church leaders have plenty to say on how people should behave, on issues of "morality."

Somewhat ironically, the church is also key in providing shelters for women fleeing violence. By law, each of Russia's 85 subdivisions must have a refuge for women seeking safe-keeping from domestic violence. But they cannot cope, and the church and independent charities have stepped in to help with the massive overflow, dispatching their volunteers and workers to hospital beds in search of women in need.

Many of the shelters are hidden and disguised, scattered across its eleven time zones stretching from the Baltic Sea in Europe to the Pacific Coast bordering Japan. Little Stork, where Maria and Andrei live, is typical in this sense. Consisting of nothing more than a four-bedroom flat, the shelter is tucked away in a cluster of Soviet-era tower blocks in a residential part of Yekaterinburg. Muddy paths join the concrete buildings to each other. There is no signage. Nearby, teenage boys play football, unaware. Inside the flat, a video camera focuses on the front door. For their protection, the voices of the four residents and their children are recorded, twenty-four hours a day.

Yekaterinburg, Russia's fourth-largest city, is the only place in the country to officially declare a spike in domestic violence incidents since the new legislation came into force. But lawyers representing domestic violence victims and their families say the number is rising across the country.

Since February, telephone calls to the police in Yekaterinburg have skyrocketed, and the actual rate of cases has jumped by more than half. Those admissions may be down to the city's mayor Yevgeny Roizman, a rare voice in Russia's vast sea of obedient public servants.

Roizman says he does not oppose Putin, but he is vocal in his support of those who do. At 55, Roizman is raffish, with a muscular build and a preference for sneakers and hoodies. He remains deeply popular with his voter base.

Roizman compares the city's rampant heroin problem (post-decriminalisation of drugs in Russia in the early 1990s), to the changes in the domestic violence law. 'The mental perception is that you weren't allowed to do this before, but now you can. The barriers have been taken away,' he tells me.

In the first eight months of 2016, his city of 1.4 million registered 400 criminal cases of domestic violence, that is, under the old legislation, before it was decriminalised. If we look at the first eight months of 2017, only 56 criminal cases of domestic violence were registered, but there were 600 administrative cases, meaning perpetrators accused under the new, lighter law. All cases involved men beating women.

Russian women are increasingly finding themselves at a time of shrinking freedoms. Along with domestic violence, the church is also encroaching onto women's reproductive rights. In recent years, anti-abortion organisations have mushroomed across the country, holding rallies and picketing clinics. One such group, For Life, has been actively petitioning the government to remove abortions from the free national health care system. The group has also collected 1 million signatures in favour of a blanket abortion ban, including from the head of the church and Putin confidante, Patriarch Kirill.

In the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, 2,500 miles east of Moscow, a private abortion clinic has been feeling the pressure. Protesters regularly set up outside the 'Renovation' clinic, which also offers cosmetic procedures and does not advertise abortions.

Anna Kozyreva, head of marketing for Renovation, frets about the direction the country is heading. 'Banning abortion will lead women to resort to illegal measures and do them by themselves, or use unqualified people. They could end up going to veterinarians,' she told me in the clinic, nestled in a quiet, leafy area of the city. 'We have a state that promotes equality, and every woman should have a choice.'

One of the Renovation picketers, a 39-year-old called Yaroslava, scoffs at the idea of gender equality. The former heroin addict, now a mother of four, had the same number of abortions when she was younger. 'But I saw Jesus, and I was saved. Now these women have a choice: kill fellow Russians, or don't and avoid punishment,' says Yaroslava, who declined to give her last name.

She explains how Russia is finally on the right path, once again, after misspent decades as a non-believing, secular state. Putin is a tsar, Yaroslava says, a father to all Russians. 'He restored our greatness,' she says, her eyes glistening with enthusiasm. 'And we must obey him.'

Reporting for this article was supported by a grant from the International Reporting Project.

'The Warriors' is a year-long reporting project by ELLE and the Fuller Project for International Reporting, funded by theEuropean Journalism Centre via its Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme.