When I first picked up Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Americanah, I had no idea how much it would impact my life. A powerful story of an African woman who discovers love and identity while living in America, it gave me a lightbulb moment when I realised I had never not considered the impact of my skin colour in most of my daily interactions.

My grandparents left Jamaica in the Fifties and settled into south London and, although Brixton was ablaze with riots a month after my birth, my childhood was a comfortable mix of metropolitan London within a large Jamaican community. At home I ate fried plantain and jerk chicken, but outside I listened to grunge and read Barthes. As a teenager, my friends and I would sneak out into the forbidden underworld of Brixton and Notting Hill in search of clubs and soundsystems, and, subconsciously, perhaps, looking for something I felt was missing.

My grandparents spoke with a Jamaican lilt, but I sounded like the middle class Brit I was and, although I always questioned my duality of race and culture, I got to the age of 35 before visiting the country I thought of as my other homeland. As a child, whenever I asked if I could go, my parents would brush me off with, 'There's nothing there for you: Jamaica is full of drugs and violence.'

But I knew they missed it. My maternal grandmother would often reminisce about her childhood home in Treasure Beach, in south-east Jamaica. She would describe how pretty it was, and how near the sea, and I would try to imagine, in grimy, wet, cold south London, what that must have been like.

Fast forward 20 years, and working as a publicist and bookseller, it wasn't long before Jamaica's biennial Calabash Festival came onto my radar, a celebration of literature, music, food and culture. When I discovered it was held in Treasure Beach, that was the sign I needed. I was going back to my roots.

THE HOMECOMING

In May 2016, after a 10-hour flight and three-hour drive west from Kingston, I finally got to see my family home. It was, as grandma described, right on the beach, and it took my friend Zoë and me just 30 seconds from front door to water for our morning swim. The big resorts have taken over many beaches, so a lot of Jamaicans have never swum in the sea, and I realised how lucky I was that my grandma grew up beside a public beach, as there are so few left.

I fell in love with Calabash Bay. A peaceful place, it's one of the four unspoilt sandy bays along the six-mile stretch of the remote Treasure Beach, where fishermen mend nets next to brightly painted boats. We fell into an easy rhythm of swimming, breakfasting on ackee and saltfish and listening to world-class writers such as Eleanor Catton and Marlon James at the festival. I met countless cousins and family friends and loved hearing all their tales of island life.

I immediately clicked with one cousin, Dwayne, a chef, and we spent hours comparing our lives. I wondered what my world would have been like had my grandparents not left, and when Dwayne said he hadn't seen much of Jamaica outside his home parish of St Elizabeth, we hatched a plan …

THE ROAD TRIP

Six months later I'm on a plane to Montego Bay, ready for an eight-day road trip down to Kingston. It's night when we land and my aunt Pamela whisks me off me for rum punch and curried goat – my favourite Jamaican dish – before heading to her beautiful bungalow up the hill behind Montego Bay. I fall asleep to the sound of reggae and frogs.

I'm woken by the familiar smell of breakfast: ackee and saltfish with boiled green banana and fried plantain. Pamela wants to show me Rose Hall, the great plantation house where, legend has it, Annie Palmer, the 'White Witch', murdered three husbands and her slave lover. It's a beautiful relic from a troubled time.

A five-minute drive from here is the Half Moon Hotel, an expansive, white-columned building, originally a plantation house too. My suite has a huge four-poster bed, a large living room, a balcony overlooking a seven-mile private beach and the biggest bathroom I have ever seen. As far as Dwayne is concerned, this is definitely how the other half live.

I head to the spa for a massage and soon lose myself in the scent of allspice, ginger and orange. The tourist industry can feel removed from Jamaican culture, but here the treatment rooms are named in Arawak, the indigenous language. When I was unwell as a child, my grandma would rub warm white rum on my chest, so it is a moving moment when they use a splash of rum in the massage.

We are planning to cross the country from north-west to south-east, into the countryside, where most Jamaicans live. You can easily hire a car but, short on time, we book a local driver, Dougie, from Latitude Jamaica. He drives us to Cockpit Country in Trelawny Parish, 45 minutes south-east. It's home to the Jamaican Maroons, escaped slaves who fought for autonomy in the 18th century. My maternal grandfather is descended from the Maroons and I'm intrigued to see what it's like. We drive through dense rainforest,full of low conical hills – lumps of limestone, which erode to create sinkholes and caves, making the landscape practically impenetrable, something the Maroons used when fighting the Spanish, then the British. The route is beautiful: so green and raw and wild, and so far from my usual love of Scandi minimalism. I feel blessed to be here.

The road winds through the little towns of Jackson, Albert and Clarks, past children playing, men leading donkeys carrying sugar cane, women balancing baskets of food on their heads, and huge roadside soundsystems. We stop in Albert for lunch. There are no other tourists, and although I fit in colour-wise, culturally I am European, and it shows: I'm wearing sunglasses (Jamaicans never use them) and have cropped hair (Jamaican women yearn for long), but people smile and nod and I feel at ease. We queue for a busy, unnamed restaurant in a shipping container, where they've disappointingly run out of the famous yams that local hero Usain Bolt (from the nearby village Sherwood Content), attributes his speed.

Half Moon Hotel, Rose Hall, Montego Bay (+1 800-626-0592, Half Moon Hotel). Doubles from £227, room only. Luxury resort with 197 rooms, some with private pools, 13 tennis courts, and two-miles of private white sandy beach.

OCHO RIOS

After six hours on the road, we arrive in the biggest town in St Ann's Parish, Ocho Rios, and at the pretty Jamaica Inn, a plantation house-style hotel built in the Fifties. It reeks of old-school glamour, with photos of Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller (who holidayed here), and paintings of Jamaican artist Albert Huie. I love that the phrase 'shaken and not stirred' was (supposedly) coined at the great mahogany bar, when Jamaican resident Ian Fleming and Winston Churchill were ordering martinis. My room is a beautiful two-bedroomed cottage opening on to the sea. I want to stay forever.

After one night, we drive two hours east to the Blue Mountains passing through Fern Gully, a three-mile stretch of more than 300 varieties of fern fores. I stick my head out of the car window and look up, glimpsing patches of blue sky through the canopy of vivid green until the heavens open in a dramatic rainstorm as we wind up hairpin bends 3,000ft into the mountains.

Jamaica Inn, Main Street, Ocho Rios (+1 855 441-2044, Jamaica Inn). Doubles from £270, room only. An elegant, colonial-style beachfront hotel. Each of the 52 rooms, suites or cottages has a veranda or balcony.

Strawberry Hill

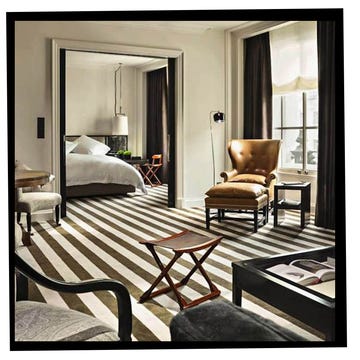

A former coffee plantation (Blue Mountain coffee is some of the best in the world), Strawberry Hill is owned by music mogul Chris Blackwell and famed for its musical gatherings and Sunday brunches frequented by uptown Kingstonians. But its main claim to fame is that Bob Marley, Blackwell's friend and protégé, recuperated here after being shot in 1976. The hotel has just 13 rooms, cottages and villas spread over the hillside, some with hammocks and outdoor showers. Inside the look is colonial, with heavy teak four-posters swathed in mosquito nets. I'm given a beautiful cliff-side room named after Junior Gong, one of Marley's sons.

We sign up for a three-hour Gordon Town Trail with a wonderful guide named Ricky, to explore Strawberry Hill's stunning surroundings. As we follow the Hope River downhill, he regales us with tales of surviving hurricanes and his life as a Rasta, pointing out trees and exotic flowers. We edge past sheer drops, looking down on the river rushing through ravines, and at the final waterfall I strip off for a quick swim: after the exertion of the climb, the sensation of cool water is exquisite.

Back at the terrace of the Strawberry Hill restaurant, a duo of oxtail and goat curry with rice and peas sets us up for a night on the town. In a sports bar in a car park (opposite Kingston's American Embassy), a local crowd (I'm the only tourist) is focused on an intense pool tournament. Jamaicans love street games, so I try the bingo. The caller is hilarious, and despite it being fast patois, I actually understand, quickly filling my card and winning JD$900(£6). The music is popping from under a gazebo, and celebrating with rum & Ting, I couldn't feel happier.

Strawberry Hill, New Castle Road, Irish Town (+1 800-688-7678 Strawberry Hill). Doubles from £240, room only. 13 cottages and villas set around a beautiful 18th-century plantation house in the Blue Mountains.

Kingston

Kingston has a bad rep, but I'm curious, so we check into the Terra Nova hotel, which is evidently the local go-to for celebration lunches, despite being slightly corporate. At the nearby Bob Marley Museum cafe, it's filled with French Rastas – and it's strange to suddenly be with so many tourists.

I meet two local filmmakers, Sarah Manley and Michelle Serieux, at Devon House, a beautiful Kingston mansion built by Jamaica's first black millionaire, George Stiebel. Striking an instant rapport, we talk about Jamaica, hardship, the film industry and women. Then tonight there's a dinner party at the beautiful mid-century home of Annie Paul, who works at the UWI (University of the West Indies). We are a range of nationalities: Indian, Egyptian, Syrian, white American, mixed-American, Canadian, Jamaican, Chinese, and me. We eat, we drink, and the chat flits between art, politics, education and literature.

On our last day, Dwayne and I plan go to downtown with Dougie. Dwayne is apprehensive about the perceived violence of the area as many Jamaicans are, but I'm struck by how beautiful (and unthreatening) it is. The churches and theatres are either Victorian or mid-century and it's buzzing with people. The boys stop to get cow-skin and chicken-foot soup, known as 'leather 'n' stepper'. I'm too full of ackee and excitement to try it.

Coronation Market is the biggest market in the English-speaking Caribbean. I stand out as the lone tourist, but with two Jamaican men in tow, no one pays any attention. The sights, smells and sounds are intoxicating, with each row of stalls named after fruit and vegetables: Mango Way, Pineapple Road, Avocado Avenue.

Dougie has family in the formerly notorious drug hotspot of Tivoli Gardens. There is no sense of trouble when we visit, though. Women sit braiding each other's hair, while children play in the street and boys dance to the latest sounds blaring from speaker towers.

We've seen posters for a dance event called Mellow Vibes, so we head Downtown to the stadium, pay the equivalent of £10, and walk into a huge bashment of 3,500 people. The music is amazing: old-school tunes, reggae, hip-hop, slow jams. Everyone is dancing and I can see, despite the hardships, Jamaicans have a very peaceful, fun-loving culture: often reserved, but generous and proud. At 4am, we buy jerk chicken from one of the many barbecue stands: juicy, flavoursome and fiery, a fitting end to the trip.

Back in London, I often remember that night, grateful to have gained this unique perspective of a place I can now, truly, call home. It was fascinating being on holiday in a country where people share my skin colour and the culture of my youth. I keep thinking back to Americanah, and how every journey helps to make you who you are. This trip had a huge impact, giving me a better understanding of myself, my family and my people. I was blown away by my time there; chatting in Patois, eating the food of my childhood in the blazing sun, listening to music with basslines that vibrated in my soul. It was profound, extraordinary – and has made me feel, finally, like a whole person.

Terra Nova Hotel, 17 Waterloo Rd, Kingston (+1 876-926-2211 Terra Nova Hotel). Doubles from £185, B&B. This boutique hotel with 41 rooms is set in a converted former great house.

British Airways (ba.com) has return flights from London Heathrow and Gatwick to Kingston and Montego Bay, from around £590. For more tourist information, see here.