It was Flo Kennedy who kicked it all off—by dying, that is. The iconic lawyer and activist lived out the end of her days at home, a New York Times obit published on December 23, 2000 reads. She was 84.

I, meanwhile, was in the fourth grade; Amelia Earhart and the pink Power Ranger were my premiere feminist touchstones; and if I'd ever noticed the obituaries section before, it was only because it was–and remains–my mother's favorite to read, and she still tends to leave it open while she roots around for a pair of scissors to cut out some notable entry.

Florynce Kennedy

Of course, the scissors came out for Flo. The obit was peppered with some of Kennedy's best quips, the stuff Etsy embroidery stores would be made of years later. "I find that the higher you aim, the better you shoot," she wrote of her decision to take pre-law courses at Columbia University instead of studying to teach grade school, as would have been expected of her; and, "Sweetie, if you're not living on the edge, then you're taking up space."

She was "an icon," my mother's highest praise—an advocate for civil rights, a wearer of cowboy hats and pink sunglasses, a fighter "in the courts and on the streets" for the Black Panthers and the National Women's Political Caucus. (It was only when I came across the obit again over a decade later that I finally read it in full and learned that Kennedy had once led a "mass urination" at Harvard to protest the absence of ladies' restrooms. What a woman!)

At the time, I knew only the barest details of the women's and civil rights' movements. A dozen years in classrooms later, I still think the Times has given me my most complete education in recent feminist heroes. Bookstores are scarcely more helpful; according to Slate, 71.7 percent of biographies published in 2015 were focused on men. Even in pre-pubescence, I grasped that women like Flo Kennedy were influential and important and that I wasn't likely to learn about them in middle school.

So, my mother intervened, reciting bits and pieces of the most scissor-worthy obits while I ate breakfast or did my homework, entire histories of forgotten feminists printed in the New York Times, her bible. I guess she skated over all the illness and disease, because it wasn't until a few years into the habit that I realized everyone was dead.

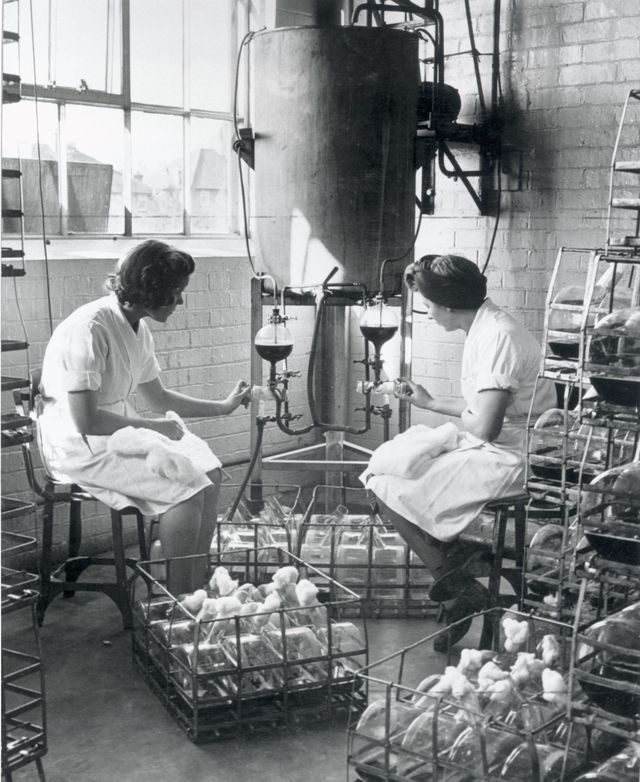

Mildred Jeffrey

I must have been reading the obits on my own by 2004, because I vividly remember Mildred Jeffrey, who was 93 when she died in Detroit. Jeffrey was the eldest of seven children, born in Iowa. A passionate supporter of women's and workers' rights, she organized laborers across the South and on the East Coast, eventually taking a job at the United Automobiles Workers union. She organized the union's first women's conference, ran its radio station, and headed its consumer affairs office. In between, she founded the National Women's Political Caucus and helped convince Walter Mondale to tap Geraldine Ferraro to be his running mate on his 1984 presidential election ticket. A lesson there, from the obits: No woman arrives in her historical moment on her own. Behind her, there's always an army of others, urging her forward.

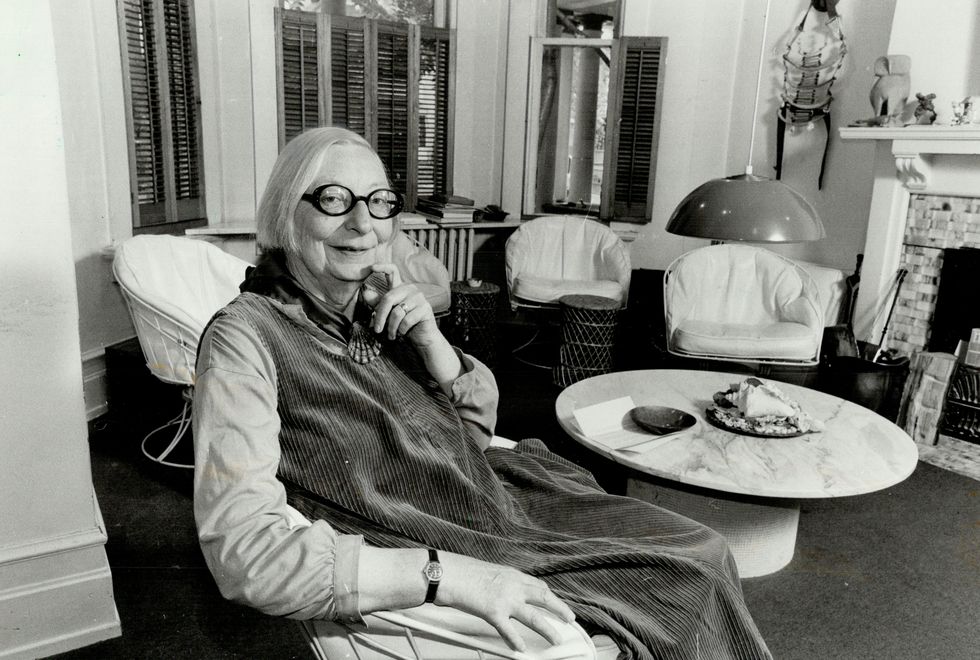

Jane Jacobs

Two years later, Jane Jacobs died in 2006. She was 89. Eventually, I would take an entire seminar that based its curriculum on her work, but it's thanks to the Times that I know she once said, "I hate the government for making my life absurd," a sentence that I've taken to repeating with renewed zeal over the past several months. And I owe Jacobs for revealing to me the obit section's awful blind spots, too. Jacobs "became a beloved intellectual pioneer characterized by a dumpling face," the Times writes. Oh.

Yvonne Brill

Seven years after that, actual rocket scientist Yvonne Brill died at 88 and the newspaper began her obit with a line that complimented her for making "mean beef stroganoff" and went on to remark that Brill "followed her husband from job to job and took eight years off from work to raise three children" before it so much as mentioned that Brill invented propulsion processes that we still use to keep satellites from falling out of their orbits. (Public outrage was fierce and swift, with former public editor Margaret Sullivan weighing in on Twitter and the Times itself editing the obit to better reflect Brill's actual scientific achievements.) Such missteps aren't unique to the Times. Colleen McCullough's obit went viral in 2015 after the author of 25 novels and international bestsellers was remembered in The Australian thusly: "Plain of feature and certainly overweight, she was, nevertheless, a woman of wit and warmth." Nevertheless.

But whatever their blunders, I can't stop reading, because if I did I wouldn't know that Beate Gordon was just 22 when she "almost single-handedly wrote women's rights into the Constitution of modern Japan." And where would I have found out that Rosalyn Baxandall, who died in 2015, is the reason I could even write my junior thesis, seeing as she was the one of the first feminist historians to put pressure on universities to study the role of women in the workplace at all? Never mind that she helped create the Liberation Nursery, the "first feminist day care center in New York" and a place that still exists and should be franchised like Drybars.

Aileen Hernandez

A few months ago, Aileen Hernandez died at 90. A top-ranking official in the women's movement and one of the first black women to establish herself within a far-too-white enterprise, Hernandez was the second ever president of the National Organization for Women, succeeding Betty Friedan. She was the only woman to be appointed to President Lyndon Johnson's Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 1965, "[b]ut exasperated with the slow pace at which the commission was addressing sex-discrimination cases, she left after 18 months," the Times writes. Still same, Aileen. Still same.

Without the obits, I wouldn't recognize the names Ruth Hubbard or Mildred Dresselhaus, "the Queen of Carbon Science." And I wouldn't have a clue who Roxcy Bolton was, the "feminist crusader" who made it her mission to get hurricanes named after men and died at 90 last month. (Women, Bolton said, "deeply resent being arbitrarily associated with disaster." Later, she jokingly campaigned to have tropical storms be called "him-icanes," instead.) More crucial, she founded the first rape treatment center in the country at the Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami.

Jean Sammet

Just this weekend, the Times published an obit for Jean Sammet, the trailblazing computer scientist who co-created COBOL, one of the world's first computer programming languages. I can't write code, but I do know that when Sammet designed COBOL to make it accessible to the widest possible swath of programmers, she charted a course for future generations of women in STEM. No small feat.

Since Flo, I've devoured the stories of women who toiled under condescending men, moronic politicians, egotistical bosses in white coats and black robes and countless suits, who did thankless work, who followed their instincts toward scientific revolution, who took it all so that we could talk to computers and understand the universe and see ourselves in books and universities, who laid the battle plans for wars we're still fighting, who sometimes made headlines only when they died.

And if it weren't for the obits, which remember not only the work, but its controversies, I might not have as firm a grasp on how white women pushed black women out of "women's lib," how immigrant women worked in coalition for decades before a certain president threatened us all, how Ruby Dee, the actress and activist, picketed theaters that didn't cast black performers and spoke out against all-white or mostly-white film crews in the 1940s and '50s. She died in 2014, but her job is far from done. Last month, the estate of Edward Albee refused to allow a production of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? to move forward when it discovered a black man would play a character who's described as having blonde hair and blue eyes.

And if this all sounds a little rah-rah, gooooooOOoooOOo women, where is your critical lens, I don't really care. Women feature less prominently than men in history books, lesson plans, museums, even the obits themselves. Every time I read about one who tried to give me and women like me—and okay, yes, let's make it about them; men, too―the opportunity to live the lives we choose, to study what we wish, to have the jobs we want, to cook beef stroganoff without mention, I'm earnestly, ludicrously grateful. I run to find a pair of scissors.