Devika Biswas may be short and slow-moving because of her diabetes, but you do not want to get in her way.

Armed with a notepad, a pen and a battered old phone, she storms through the hospital’s grimy corridors demanding doctors, interns, nurses – anyone – take her to see two women who are in serious pain. They've both been brought in following a botched operation in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand, close to Bangladesh.

As she wizzes through Patliputra Medical College and Hospital, stepping across pregnant women sprawled out on the floor, and a few cows on the perimeter, she stops to complain to anyone who will listen that the toilets are overflowing and there’s no water for patients to wash their hands.

She arrives at the emergency ward to meet two women who are lying on metal gurneys clutching their stomachs riddled with stitches. Both have an IV drip attached to their wrist and their husbands by their side.

A few days earlier, the women had been sterilised – a common and permanent method of contraception commonly known as tubal ligation where the fallopian tubes are cut, tied or blocked – at their local primary health care centre.

The women live in a village on the outskirts of Dhanbad, a nondescript yet loud town with a constant flow of trucks from the mines driving through it. It’s the second-largest city in Jharkhand – a state that is famous for its national park filled with tigers and elephants.

The doctor performed more than 30 operations in just two hours, leaving two women fighting for their lives. While those numbers might sound shocking, it's sadly not unusual. In one of India's most famous botched sterilisation cases, 80 women were sterilised in five hours by one doctor.

'There were so many people at the camp, the doctor rushed,' says Pouki Devi, 36, dressed in purple pyjamas.

She had fallen unconscious after the doctor nicked her bladder.

Gudiya Devi, 30, lying next to her, murmurs that the same thing had happened to her. She winces in pain as she reveals her swollen belly covered in white bandages.

'I don’t understand what has happened,' Gudiya’s husband, Gopal, says angrily.

Devika asks the family for any documents they have – such as medical expenses they’ve incurred at the hospital – and for a detailed account of the day.

She promises to report the incident to the government, jotting down words in her notebook and taking a few photos of the women and their wounds before winding her way through the hospital once again to find the head of the department.

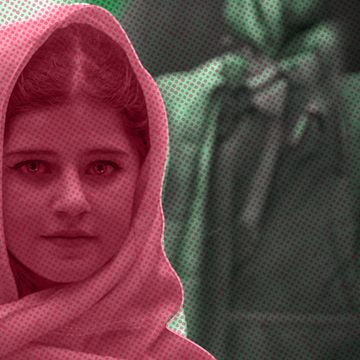

You see Biswas, a bespectacled women’s health activist with black hair and silver roots, is on a mission: a fact-finding mission to save women’s lives.

'I come from a very simple village, but I’m fearless,' she says.

Biswas was inspired by her aunt’s work as a doctor during British colonial times. She knew she likely wouldn’t become a doctor but she was frustrated at the government’s focus on 'population control' rather than preventing health problems and promoting good health. So she decided to speak up for women and their reproductive rights.

Biswas works alongside the National Alliance on Maternal Health and Human Rights and Healthwatch Forum, two Indian organisations that monitor reproductive violations against women in the most far-flung areas of the country.

'No one monitors the sterilisation camps because no one thinks anyone will come and ask about them,' she says. 'No one will say anything because it’s not a death; no one cares about botched operations.'

'The government is to be held accountable when gross violations happen.'

For decades, sterilisation camps have been at the forefront of India’s efforts to combat population growth. Unlike China, which until recently had a one-child policy to slow population growth, India’s government offers cash incentives to women and men who choose permanent sterilisation. But this approach has disproportionately focused on the rural poor and uneducated – those who are blamed for India’s burgeoning population and thus its woes from poverty to hunger.

But sterilisation targets, plus cash incentives for doctors and female community health care workers who bring women to the camps – which are run by state governments or outsourced to local NGOs – have led to mass operations, often in unsafe conditions.

Women as young as 18-years-old are being operated on.

Every year, approximately four million women undergo sterilisation in India, more than in any other country. But male sterilisation is decreasing, from 1 to 0.3 percent in the past decade.

More than 4,000 miles away, in the UK, about 13,000 women undergo sterilisation through NHS England every year. The true number is unknown, though, because a large number of procedures are carried out in the private sector.

This figure used to be much higher, but due to the increased popularity and availability of long-acting reversible contraceptives such as implants and IUDs, fewer women are opting for the permanent method.

Depending on where they live, Indian women are given anything between 1,400 to 3,000 rupees (£15 to £33) to undergo the procedure. Women who live in areas that are declared 'high fertility', like the tribal areas of Jharkhand, are offered more money.

In early 2012, in Bihar, one of India’s poorest states which borders Nepal, a surgeon sterilised 53 women on school desks under torchlight, otherwise surrounded by darkness, during a mass camp.

During the procedure, one woman suffered a miscarriage, and three others lost significant amounts of blood. The surgeon never changed his gloves, there was no running water and the medicines were past their use-by-dates.

After hearing of the incident, Biswas went back to her home state of Bihar, where she was born and raised, on a mission to gather facts. She was lost for words at what she heard.

She recalls what the woman who had been operated on while being pregnant told her: ‘For the government, people like me, life has no meaning so they can do anything with us.’

'It was so difficult for me to digest all that had happened. How is it possible that the government can do this? I felt so miserable,' says Biswas.

Nautrally, Biswas decided to do something about it. With help from lawyers in New Delhi, she filed a petition to the Supreme Court based on her findings.

'I filed this case because it really touched me. We do not treat the poor as human beings. We think they are … less than insects,' she says.

After a four-year legal battle with the government – during which time, we saw the deaths of 15 women in another sterilisation camp in central India – in September 2016, the court ordered the government to shut down sterilisation camps across the country within three years.

The camps, the court judgment said, infringe on the 'reproductive freedoms of the most vulnerable groups of society whose economic and social conditions leave them with no meaningful choice … and render them the easiest targets of coercion.'

The verdict issued several important directives, including that governments no longer stipulate fixed targets for sterilisation so health care workers and others don’t compel or force women to undergo such operations; to increase compensation for sterilisation deaths and botched operations; and to mandatorily explain to patients, in his or her language, the impact and consequences of the procedure.

While women will still be able to undergo sterilisation, camps run by state governments or local NGOs will be illegal.

The verdict was hailed as a historic victory for women’s rights activists across India, including Biswas.

They hoped the verdict would propel India to move away from family planning policies that put the onus on women and to instead provide a wider range of contraceptive choices and increase the uptake of male sterilisation.

'Women do not need to be pushed like cattle into camps and forced to be sterilised,' says Sarita Barpanda from Human Rights Law Network.

But almost two years on from the judgement, has anything on the ground changed?

Camps in many parts of the country continue to thrive in the same way and state government targets for sterilisation are still being enforced, health activists say.

For them, it’s an indication that come the 2019 deadline, not much will have changed.

'It’s actually naïve to imagine that orders passed by the Supreme Court would lead to significantly changed practices on the ground,' says Jashodhara Dasgupta, founder of SAHAYOG, an NGO which works on maternal health and rights.

Dasgupta says deaths and botched operations – including operating on pregnant women – that are routinely reported in local media are just the tip of the iceberg.

But because of the pressure put on community health care workers to take women to be sterilised 'the notion of free choice is being violated'.

'We have to stop providing incentives and instead provide quality services,' says Dasgupta, who now works as the executive director of the National Foundation for India in the capital, New Delhi. 'When you believe in women’s reproductive rights, then change can happen.'

Biswas agrees that incentives for sterilisation must be abolished. She’s also fearful that by redefining camps – calling them something else on paper – will mean they will flourish without any external monitoring.

'They (state governments) are still doing camps but without saying it’s a camp so on paper it becomes a ‘health day’,' she says.

'Moving forward there will be fixed dates, which means a doctor will allocate a day a week for sterilisation so anyone who wants to come on the day, the operating theatre will be ready.'

While she hopes this may mean hospitals and primary health centres will be better equipped for sterilisation, she worries about the broader issue at hand: Is India ready to shift its focus away from female sterilisation?

For that to happen, other contraceptive methods don’t just have to be available, but women have to be educated and empowered to make informed choices. The government has pledged to increase women’s modern contraceptive use from 53.1 percent to 54.3 percent; ensure that 74 percent of the demand for modern contraceptives is met; and to roll out an increased range of contraceptives by 2020, in line with the global Family Planning goals.

But the oral contraceptive pill and IUD is hugely unpopular, considered taboo and shrouded in myths. In many rural parts of the country, sterilisation is the only option because other choices are frequently unavailable due to of a lack of trained healthcare workers and supply chain problems.

Condoms, on the other hand, are shunned by men and also considered taboo. And while men are provided larger financial incentives to go for a vasectomy (male sterilisation) – an easier operation with a quicker recovery time – it remains unpopular, partially driven by the widespread belief the procedure will reduce male libido and make sex less pleasurable.

'Men need to take responsibility and be part of family planning,' says Poonam Muttreja, executive director of the Population Foundation of India.

For now, Biswas knows she has her work cut out for her.

'So many people are not aware of so many of their basic rights,' she says as she takes her diabetes medicine. 'Even if I wanted to stop, I can’t.'

The phone rings, and she answers without hesitation. It’s another call for help.

'The Warriors' is a year-long reporting project by ELLE and the Fuller Project for International Reporting, funded by the European Journalism Centre via its Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme.