This feature is part of ELLE's 'Modern Motherhood Series' - exploring the shifting role of 'mother' in society and the women choosing to do things differently.

Three years ago, Genevieve Roberts was on holiday in Sri Lanka. Until this trip, the promise of exploring a new country magically fixed any twinges of discontentment in her life. Now? Well, she couldn’t shake the feeling that something important was awry. Was she having a mid-life crisis? She wasn’t sure. Despite a successful career in journalism, her own flat in South East London and loving friendships, she felt unfulfilled.

After divorcing her husband aged 30, the author hadn’t thought about fertility. She was still young, and while she wanted kids, there was no rush. Seven years later, however, on a beautiful Sri Lankan beach, the realisation hit her: she was 37-years-old, single, and wanted a family.

The notion of having children, she writes, had become an ‘ache that was beginning to dominate my thoughts.’

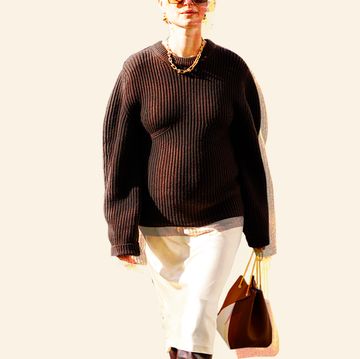

After a precautionary test revealed low fertility – and with time ticking – she decided to go it alone. A consultant suggested IUI (artificial insemination), where the sperm is inserted inside a woman’s uterus. Or rather, ‘one step up from a turkey baster’, says Roberts. After the second round, she fell pregnant with her daughter, Astrid, who is two years old. Now eight months pregnant with her second child, also conceived via a sperm donor, Roberts has documented her experience in Going Solo: My Choice to Become a Single Mother.

Now 40, she acknowledges that life hasn't exactly happened the way she planned. ‘I don’t doubt that the ideal way for a child to grow up is with two loving parents,' she writes in her book.

But, as Roberts explains today, ‘I just couldn’t bare the idea of not trying to become a mother. If you have a real longing to become a parent, it's great to know that you have a choice – especially as a woman. And it’s better than panic dating.’

The weight of responsibility

Weeks after making the decision, Roberts ordered three vials from an American sperm bank. She compares it to a dating website, only with ‘no flirting and a lot more baby pictures.’ It might sound clinical, but a growing number of women are doing the same thing. Last year, the Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA) reported that the number of single women choosing to have IVF was up 35 per cent since 2014, as well as a 15 per cent rise in fertility treatments using donor sperm from 2015 to 2016.

And, by 2025, the global sperm bank business is estimated to be worth $5bn.

Cost-wise, it’s not cheap. Roberts picked a private clinic, where one round of artificial insemination costs £2,000 (if this hadn’t worked, the next option is IVF, which costs roughly £6,000 per round).

In the book, she writes frankly about finding early pregnancy tough – she becomes anaemic, yearns for someone to hug and consistently worries about the baby.

What was the hardest part? ‘Once you've had a miscarriage, I think you never relax in quite the same way during pregnancy. I really desperately wanted to become a mum but it wasn't like a positive test equalled becoming a mum – there was a lot of uncertainty. I didn’t dare hope too much because I wanted to protect myself from being hurt.’

Despite this, going solo always felt right. Or rather, she never had any doubts. ‘It’s such a thought-through process,’ she says. ‘The minute you're involved in fertility treatment, it's not like: “oh, let's just see what happens.” You plan ahead, and even further ahead because you start thinking, how am I going to juggle work with childcare? It isn’t just “well I’ll see what happens after maternity leave” – I’m the main carer and breadwinner for Astrid, and I fill both of those roles. If you had any doubts, you probably wouldn't go ahead.’

She continues: ‘I remember seeing the pregnancy stick turn positive and I felt the weight of responsibility, but it was such a welcome weight on my shoulders. I wonder if knowing there was a chance I might not become a parent made me appreciate every moment of it, more than if I’d had children in my twenties.’

After attempts to get her contractions going failed, Roberts gave birth via C-section. Her mother supported her through the first couple of days, and she hired a part-time postnatal doula for six weeks. Despite the upheaval, she was surprised by the simplicity of those first few months.

‘I think I would have wanted a partner to find me attractive,’ she says, ‘even though I wasn’t having sex. In those first few months, there’s a freedom in being able to go to bed when you’re tired rather than keeping two relationships going. You're bonding with your child, but you're also trying to be a partner to your partner. I didn't have to worry about my identity, which I think a lot of people do.’

Donor vs Dad

While Astrid is too young to understand her family set-up just yet, Roberts is very open about it. ‘I’ve already explained, in child language, that she doesn’t have a dad and was made by a donor. It’s really important she’s not surprised or her identity is shaken.’

On advice from counsellors, she’s also careful to use the word ‘donor’. ‘A donor is not a father, and ‘Dad’ can mislead children,’ she says. ‘They can get confused, and expect a relationship when it’s not a relationship. We don't quite have the language for new forms of families yet.’

In the UK, donor conceived children have the right to know their donor’s identity once they reach 18 (anonymity was lifted in 2005). If Astrid wants to try and make contact, Roberts will support her.

‘I think it’s good to put some of the jigsaw pieces together - she's a lot more sporty than I am,’ she laughs. ‘At the same time, there's no suggestion that a donor will sweep and suddenly be the dad figure, and that's something that I'll always make clear.’

Two years later, there are times when Roberts says it would be ‘wonderful’ to have a partner. Whether it’s measuring out Calpol doses or taking Astrid to A&E, she occasionally wishes for an extra hand in making decisions. 'Or just to have someone say "you're doing this really well",' she adds.

Instead, however, Roberts has learnt to trust her own instincts. She isn’t naïve, and knows that what seems easy now might get tougher later. This is why a strong support network is key, she says. Roberts is close to her family and through writing the book has met a large community of solo mums who ‘really understand’ the ins-and-outs of it all. The other big lesson? Don’t try and do it all on your own. ‘It's okay to ask someone for help, or ask their opinion,’ she says.

While some have criticised her decision (certain keyboard warriors don’t think it’s a ‘good way’ to bring a child into the world), Roberts wouldn’t change a thing.

‘It's 2019 – we’ve got lots of divorced families and single parents. People are starting to realise that support, love, and security are more important for children, not what your family looks like on the outside. And giving kids that in any form, whether it's one, two or eight parents, is what counts. Not a day goes by where I don’t appreciate Astrid being in my world. I love watching her become this person with her own views. I feel so lucky. I really do.’

Going Solo: My Choice to Become a Single Mother Using a Donor by Piatkus (£13.99) is out now. Genevieve Roberts will appear on the panel of What Comes First: The Career or the Egg? on 4th May as part of Fertility Fest (Barbican 23 April – 12 May 2019).