Do you believe in ghosts? Me neither, but explain this.

It’s late at night and I am asleep in the basement of my little Georgian house in Spitalfields, east London, right opposite the old fruit-and-veg market. That site was once a leper hospital – you can hear it in the name Spitalfields. From the late 1600s, it became the hub of London’s grocer trade – every cabbage from Essex, every apple from Kent made its way here – and, later, the entire understorey was turned into vast vaults to ripen bananas, where unseen King Kongs swung silently through the subterranean city.

Yes, I made up the gorilla part, but not the rest, because stories have a way of retelling themselves and that’s what this story is about.

My house was derelict. When I bought it, in the early 1990s, it had been on sale for 15 years. Nobody wanted to live in Spitalfields in those days – just a few crazy artists like Gilbert and George.

The deal was cash-only. No survey. Sold as seen. Nothing had been removed from its long and cluttered past. The fireplaces were boarded up – but all there. The panelling on the walls was covered over in Dulux. The floorboards were as wide as hope and as worn as many lifetimes. There was no running water. No electricity.

The upper floors had been the offices of an oranges importer. I have a trunk stuffed with the notepaper and envelopes, the address books and telephone numbers in London and Seville.

On the ground floor, a shop had opened in 1805 as a general grocer. We were selling onions the size of cannon- balls during the Napoleonic wars.

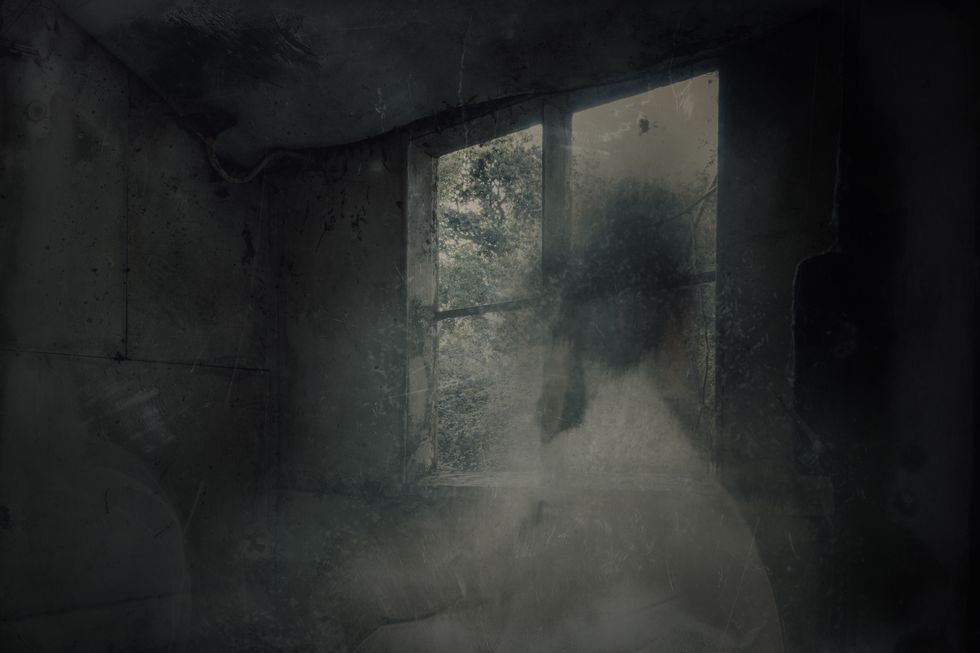

An old house, a house built in the 1780s, a house with a past. They say walls have ears, but what if walls can speak? What if our buildings are trying to talk to us?

It’s late at night. I am asleep. It has taken me two years to make the house habitable again and, for now, friends of mine are living in the upper floors. I am fine in my basement flat, the life of the city present but muffled through the iron- barred grating that sits at street level, while I am what lies beneath; unseen, unsuspected, solitary as an oyster.

Soon after midnight, I am awakened by the quick clatter of footsteps down the straight stairs leading to the basement. No carpet. I am aware that my right arm is hanging out of the bedclothes – and it is this wrist that is suddenly and lightly held by four cold fingers and a thumb.

I can hear breathing but it isn’t mine. I realise that I am having my pulse taken. I say out loud, why do I say this?– ‘I am alive...’

Immediately, the hand drops my wrist and I hear footsteps moving swiftly up the stairs. All I know is I am intensely cold. When I turn on the bedside light, I am alone.

The next day I ask my friends if they came visiting at night. Ludicrous idea, because that would mean exiting onto the street and re-entering via my private door. Later, searching for a simple truth, we discover that part of the basement is much older than the rest of the house, and may have been used as a burial pit during the plague of 1665.

What had I disturbed? What had I released?

Sitting on that stretch of stairs, I began to wonder if what I was disturbing/releasing was a part of myself. What was buried? What part of me needed to say, ‘I am alive’?

I am much older now, and one of the benefits of getting older is being able to recognise patterns in the past. When I am in trouble I seem to ‘manifest’ something that looks like it’s a random happening on the outside, but that now reads more fatefully to me – in the sense that our fate is within, not outside us, but we can’t always see it unless it appears in 3D, rather like ghosts.

I bought that derelict property because I needed to rebuild myself. ‘Inner houses, outer houses,’ as a Jewish friend of mine says.

I enjoyed early success with my first three novels – starting with Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit (1985) – and won a Bafta in 1992. That same year, I published Written on the Body, a novel where the narrator doesn’t declare their gender or their name. How you read the narrator determines how you will read everything else in the book.

The novel had terrible reviews in the UK – but that was not straightforward because, for several years, I had been having an affair with my agent, and that affair had ended. She was a powerful woman, who decided to sue me for breach of contract when our affair ended and I decided to take my previous books away from her agency. Simply put, I was too upset to ‘do business’ with someone I still loved. Someone who was gone.

It didn’t occur to me that the open doors I had walked through when she was my champion would slam shut when she wasn’t.

To add to the confusion, Written on the Body was the book that made my name in the USA. It did tremendously well. In fact, just this year, The New York Times named it as one of the 25 most influential queer novels of the postwar period. It was ahead of its time as a non-binary text. Back then, though, I had a recurring dream that I was skiing downhill, way too fast, and my skis were coming apart. I was coming apart.

I am sure that what happened to me in the basement that night really did happen – it was not a dream. The deep horror in my soul unlocked a horror that had taken place on the site of my house – and I say this because ‘time’ is irrelevant when it comes to supernatural occurrences. Ghosts ‘return’ when they have a message to deliver, as with the ghost of Hamlet’s father, or Jacob Marley in A Christmas Carol. Alternatively, they return when summoned, often accidentally, by a person or their circumstances – think of the ghosts in the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, where Jack Torrance’s own demons are soon matched by others, far worse.

This sense of place-as-player is part of the American Gothic. The twist is a kind of complicity between the land, or the building, and the arrival of certain occupants who call up, or call out, the malevolence – think Bly Manor in Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw or The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson.

Classic British ghost stories, from The Castle of Otranto (published in 1764) to the early-20th-century tales of MR James or Susan Hill’s superb The Woman in Black from 1983, have more innocence in them. The humans are victims, not accomplices.

I think we are accomplices. I believe this because many people experience nothing supernatural, even in spots reputed to be haunted, while others suffer unexpectedly in previously unhaunted places.

My ghostly experience was like finding a role of cine film that replayed itself. Perhaps engram is the right word – it means cognitive information imprinted on a physical substance. Our memories in our brains are engrams. The theory popularised by the Matrix movies, that this life of ours is a simulation, is the theory that we are a software experiment running on temporary hardware. Maybe we are – it would certainly explain why non-temporal effects, aka ghosts, have been reported everywhere in the world.

What happened to me that night was literally a wake-up call. I was losing myself in sadness and confusion. I felt dead inside. That cry from the heart, ‘I am alive’, forced me to grab at life like a rope swung in my face. It took me a while longer to really recover from the dark decade, but that in itself was part of the lesson. Recovery is slow. Remaking the self takes time, and we don’t know how much time. It is so easy to get caught in terrible things from our past; psychiatric professionals call it the ‘old present’. It should be gone. Instead, it plays on repeat, pulling us back to what is no longer there – like being haunted. Like being haunted by yourself.

My adoptive mother, the late Mrs Winterson, told me that as a baby I screamed so much for two years that they thought something was wrong with me. There was something wrong with me – I was trying to bring back my biological mother in the only way I knew how, by making as much noise as possible so that she would hear me. At the end of that episode, I never cried again. No matter what anyone did, I would not let them see me cry. I left home at 16 and didn’t look back. When I was living in a Mini or a tent, or sharing my body in return for a bed, I never cried. A fury drove me on.

The work of my life is to cry. By which I mean to accept hurt, loss, betrayal, injustice – you know the long list – and to let myself be upset, let others share that upset. My default has been the more it hurts, the more you hide it – except that you don’t hide it. It will show as rage, or what looks like its opposite – walking away without a glance. As I have softened, I have had to go through periods of frightening vulnerability. A different kind of breakdown followed in 2007. I wrote about that in Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?. But, since 2009, I believe I have stopped functioning as my own haunted house. I think those ghosts are gone.

But some ghosts are still around.

My little house in Spitalfields is home to myself and a woman in a grey dress, who often sits opposite me in the parlour when I am reading. She’s no trouble, and other people have felt her presence.

There’s a man as well, who likes to open doors I close, and sometimes to sit heavily on the bed. He also turns the radio on in the kitchen. I have had to speak to him severely, and he is much better behaved now. He just likes living here.

When I arrive at the house, I always greet my invisible tenants and when I leave, I ask them to keep an eye on the place for me. Yes, I know this sounds bonkers, but it is what it is.

My dear friend Ruth Rendell came to believe in ghosts after a nasty experience in a hotel in Cuba. Soon after she died, I was sitting in front of my laptop thinking about her, when her smiling face flashed onto the screen. It is a photo I have in my file, but I didn’t have the file open, nor had I been looking at that photo.

Sceptics will have their explanations – of the photograph, and of the rest of what is here.

Anyone who has experienced other- worldly phenomena has no explanations. We fall silent, because what can we say?

‘Night Side of the River: Ghost Stories’ by Jeanette Winterson is out now. (£18.99, Vintage)

This feature originally appeared in the November 2023 issue of ELLE UK.