The first time my father forgot how to drive, we were in rush-hour traffic on London’s busy Euston Road. Taking his hands off the wheel, he laughed as he turned to me and said, ‘Octavia, I have no idea what I’m doing.’

I thought he was joking and laughed with him until it sunk in that his smile was one of fear, not playfulness. Stifling my own panic, I tried to sound confident as I, a non-driver, gently reminded him which pedal was which. I frantically tried to figure out what to do next when, as quickly as he’d forgotten, he seemed to remember and drove home without incident. Once we’d arrived safely, I asked him what had happened; he couldn’t recall forgetting anything at all.

He’d been acting oddly for a few months. At first, we explained it as what you’d expect at his stage of life – in his 80s, he could be forgiven for asking a question twice or forgetting to lock the front door. We later learned there’s always a period of denial with Alzheimer’s disease, and my parents and I gamely stepped into that strange hinterland where half of your energy goes into keeping yourself ignorant of a truth you’re not ready to bear.

My dad had been unfailingly reliable my whole life, and when he started not showing up for our lunch dates or forgetting entire phone conversations, my first reaction was irritation.

But just after the Euston Road incident, we were at the party of a friend he’d known for more than 30 years, and he gripped my hand. Panicked, he whispered, ‘I don’t know who these people are.’

He was like a frightened child; there was no denying it any longer.

When Dad’s behaviour first started to change, I was a year into a PhD at university in London. As a teenager, the vivid imagination of my childhood gave way to a permanent restlessness. So, when I discovered that learning languages was like being given the key to an alternate reality, I went for it. I studied Spanish in Madrid, European literature in Cambridge and taught at Paris’ Sorbonne. I moved either city or country every year for five years, leaving each place just as everyday life’s inevitable mundanity set in.

Once back to London, my wheels really came off. Looking back, I didn’t want to take responsibility for anything, including my own life. On a reckless trip to Milan, I had a drunken motorbike accident, which brought my extended adolescence to an abrupt end. Out of shame, I let my parents believe I’d fallen off a bicycle instead of a Yamaha and didn’t see them until my injuries were healed. Soon after, just before my 27th birthday, I quit drinking.

At the time, I didn’t realise my decision to clean up my act was connected to what was going on with Dad but, on reflection, I think it was my first clue: in my gut I knew I had to step up. As his illness has progressed, I’ve been equally glad and astonished to be sober.

Alzheimer’s is a voracious disease that takes what it wants: 10 years of memory, personality traits, words, people, the lot. We learnt to live alongside the chaos of Dad’s regression. Dementia isn’t something you can conquer. All we’ve been able to do is stay as flexible as possible and adjust to its ever-changing demands.

My mother and I wanted to keep Dad at home for as long as we could, and both struggled to find the balance between caring for him and living our own lives. Sometimes we did a better job than others, sometimes our emotional blind spots were impossible to see past. For a while, we lost one another in the process, our relationship stripped back to tense conversations about the state of his decline, how long since his last shave, why his fingernails were so dirty.

Dad has always been quick to see the funny side. His humour carried him – and us – through the early years of his illness. I’ll never forget his amusement as he showed me his wrinkled hands and said: ‘Look, these belong to an old man!’

When I told him it was hardly surprising, given he was 85, he laughed in amazement that they were attached to him. His optimism helps us to find the humour in things whenever we can.

For my 33rd birthday, we went to a smart restaurant. The amuse-bouche was an absurd tiny plant pot of tiny carrots that you ate with a tiny spade. I looked at Dad – who would’ve normally found the whole thing hilarious – but saw he was completely disengaged. I felt a jolt of grief. He became increasingly withdrawn throughout the meal and, as our mains were cleared, his head had lolled onto his chest.

We thought he’d fallen asleep, so ordered cheese and dessert. As one waiter placed a pear-shaped confection on the table, another rolled in a cheese trolley, telling us about each one in detail.

I turned to look at Dad. His jaw was clenching, his fingers curled into fists. He was having a fit. I rang 999 as his body began to judder. ‘Does anyone have a bucket?’ I asked. ‘He’s about to be sick.’ Everything happened at once – paramedics arrived, the pear pudding wobbled on the table as someone handed me a champagne bucket just in time to catch his vomit. All the while, the cheese guy carried on with his speech. It was desperate, and also desperately funny (I’ll never look at a Reblochon the same way), but the fact that Dad couldn’t be in on the joke made me miss him profoundly.

A few months on, he’d lost almost all physical independence, and we could no longer give Dad the care he needed at home. The decision to move him into a nursing home was as difficult as you’d expect. But it’s actually fairly cheerful. There’s an olive tree outside his window, and optimistic flowers beside it. His room feels like the one I had at university – narrow, a single bed, desk, wardrobe, armchair. Life is full of comforting symmetries.

When I visit, I go past the dance studio where I took classes as a child, a pub I drank in as a teen, and I’m reminded that, when you still live where you grew up, most walks are an exercise in psychogeography.

It’s strange to think that, back then, I didn’t know there was a nursing home a few paces further. But it’s comforting that I’ve walked here in childish excitement and teenage angst – it’s testament to the fact that all things change and, no matter how painful the present might be, something new is always around the corner.

As Dad nears the inevitable end of his life, five years from his official diagnosis, it can feel absurd to move forward with mine. I’ve felt suspended in mourning as I grieve each new loss, but I can see that the temptation to stop my life and be with him every day isn’t far from my old compulsion to abandon myself to risky behaviour. If you’re lucky, a child’s love for their parent involves barely any risk. But it becomes, in the grip of Alzheimer’s, inherently risky.

Who will they be today? Will they know you? As dysphasia sets in, will they be able to swallow food, or choke with every mouthful?

The chaotic way I used to live my life primed me for the crises (ambulances, hospitals) that this disease brings – the adrenaline rush of dramatic situations is familiar; comfortable, even. But the last thing Dad has taught me is to shift from intensity to intimacy. Without his memory, some days completely without language, the most important thing I can do is the most mundane – to be there. The intimacy of just sitting with him.

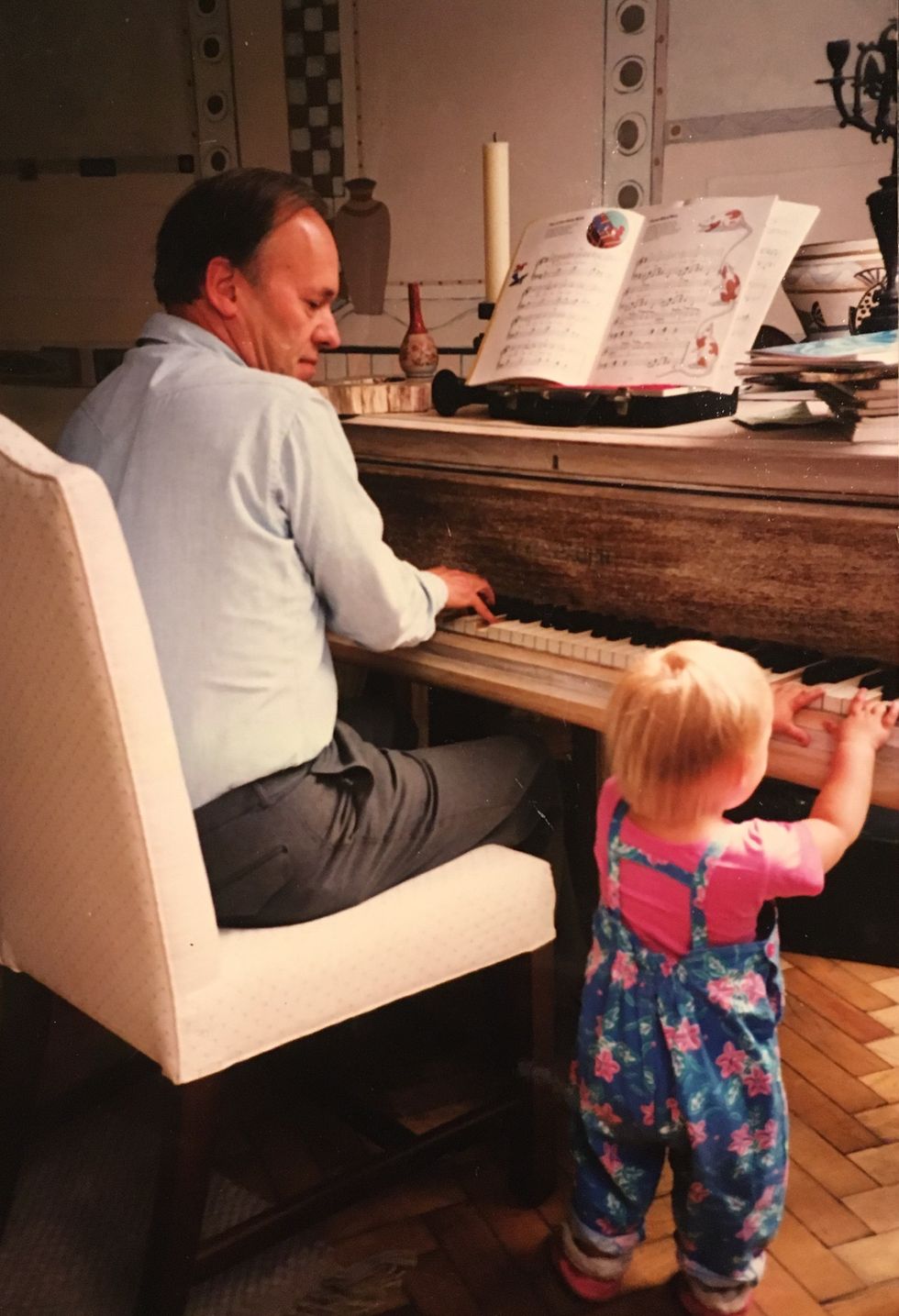

As he gets more absent, I get more present. I choose to live in my capacity for love, and it’s quiet, steadier, than I could’ve imagined. In many ways, the ultimate responsibility is for someone else, and as my father has slid further into the second childhood of dementia, I’ve found myself becoming parental. By being partly responsible for his life I’ve learnt to be responsible for my own, and I find myself wanting things I used to think were boring: roots, stability, security. I’ll always have a bolting instinct, but walking beside my father as he slowly fades has been a powerful lesson in the beauty of simply showing up.

Octavia Bright is the co-host of podcast Literary Friction. This article appears in the July 2020 edition of ELLE UK.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.

In need of more inspiration, thoughtful journalism and at-home beauty tips? Subscribe to ELLE's print magazine now and pay just £6 for 6 issues. SUBSCRIBE HERE