I was talking to a colleague recently about a friend who left university with a degree in accountancy and went on to become an accountant. To the naked eye this might seem like an ideal outcome except for the fact that almost as soon as she entered the workplace, said friend realised that she hated accountancy.

She hated spending nine hours a day at a desk, hated the mechanics of accounting and found the clients overly pedantic. After a few years of grinding, toxic dissatisfaction, she decided to leave the industry and pursue her actual dream, which was to be a tree surgeon.

At this point my colleague - who is Gen X (1965-1980) - rolled her eyes and muttered something about millennials. Okay but wait, I said. Because that’s not where the story ends. After years of studying and apprenticing, my friend finally became a fully qualified tree surgeon - and had just taken her first proper role when she had a terrible accident and a tree fell on her. She was in recovery for some months (she’s fine now) but eventually realised that if she was honest with herself, she couldn’t face another near-death incident.

'So now she’s just gone back to accounting?' She has indeed. 'That’s typical of millennials,' my colleague said. 'They just give up when things get hard.' I told the same story to a Gen Z (1997-2012) colleague who said that it was clearly a parable about the state of the working world - 'which basically f***s you no matter what you do' and that it was 'cute that she thought she could escape that basic truth.'

Personally, I think it was a freak and tragic accident, and also, maybe, a lesson that ‘following your dream’ doesn’t always guarantee that you’ll be happy. Mostly, I was struck by how much animosity both my older and younger counterparts felt towards Millennials.

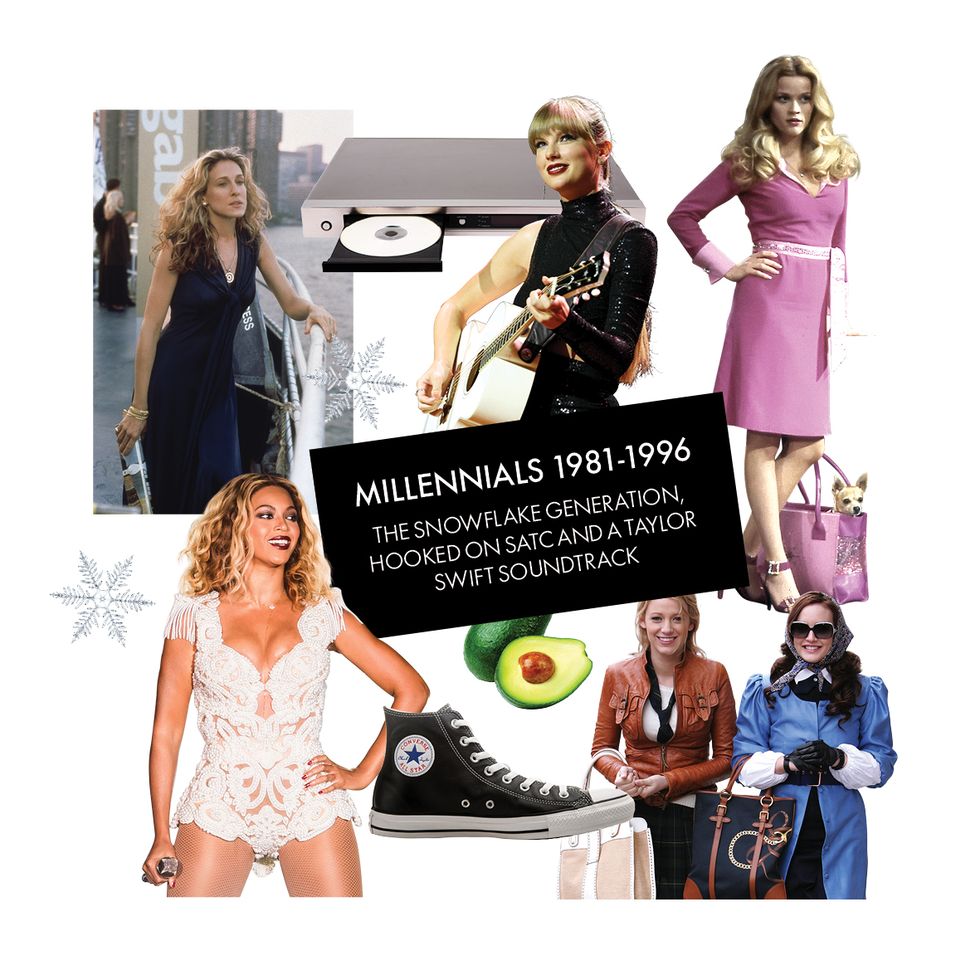

We are a much maligned generation - in my early twenties (I’m now 34), being a Millennial signified that I was an entitled snowflake. Now, with ‘elder millennials’ entering their middle age (eek), the term has come to signify all that is passé, basic, try hard and (shudder), ‘cheugy'.

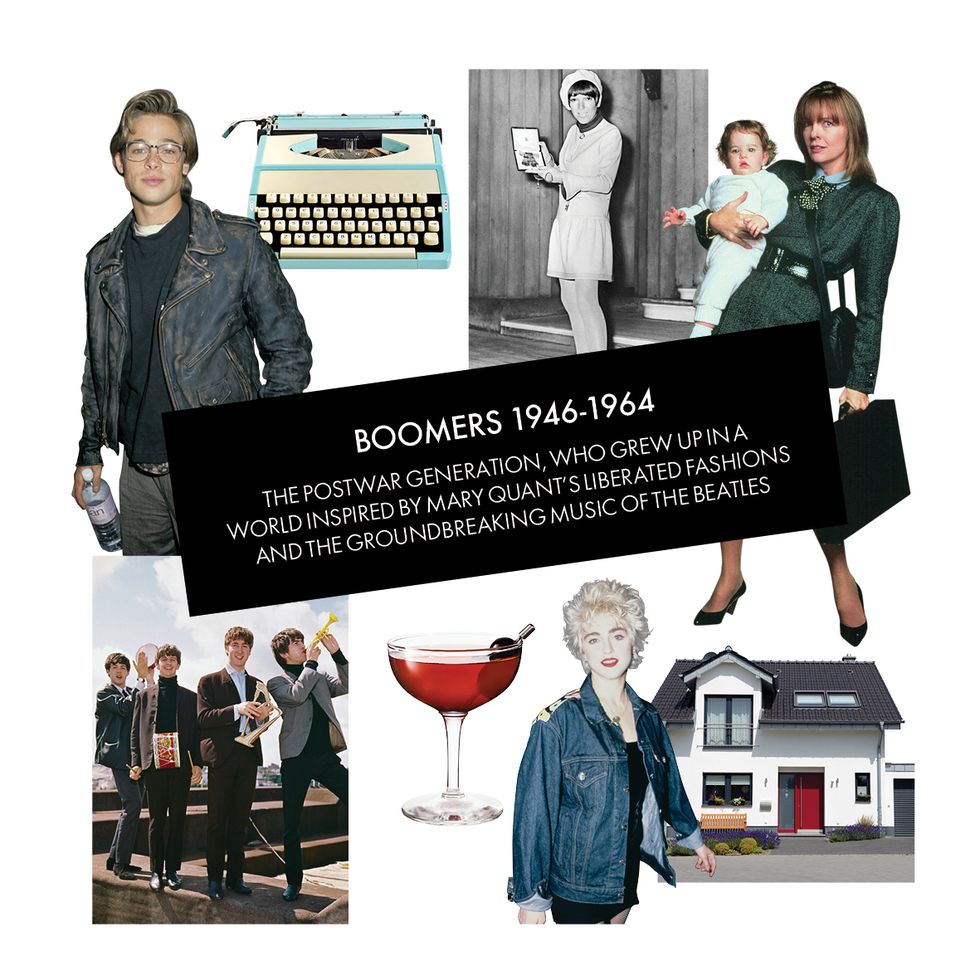

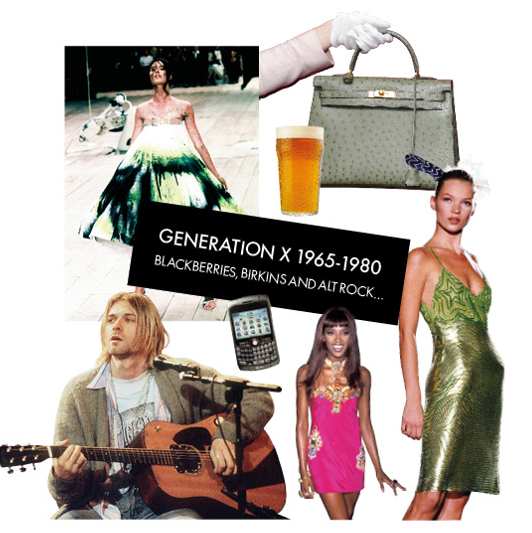

You know what I mean, right? Even while you might not know why you know - The Cut described 'cheugy' as 'hard to define, yet easy to identify' - you’re almost certainly conversant enough in generational labels to just what it means when someone says 'okay Boomer' (they came of age in times of economic boom, own huge, light-filled houses, use their index finger to type out Facebook status updates and simply don’t understand what all these young people are moaning about) or 'typical Millennial' (performative authenticity, toxic people pleasing, pale pink and #wellness - just see their hyper-curated Instagram feeds).

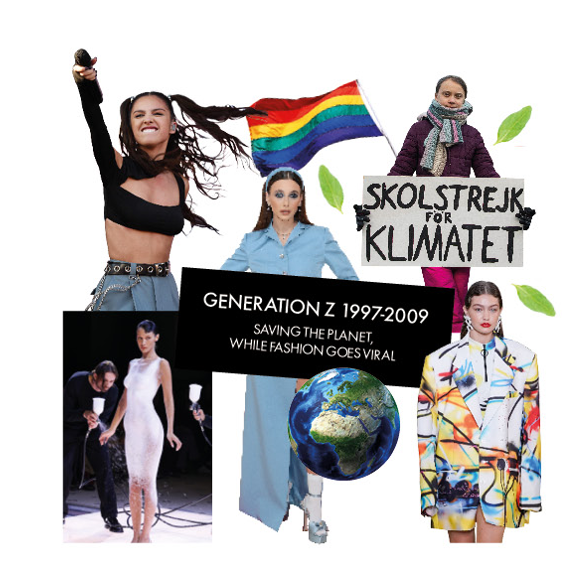

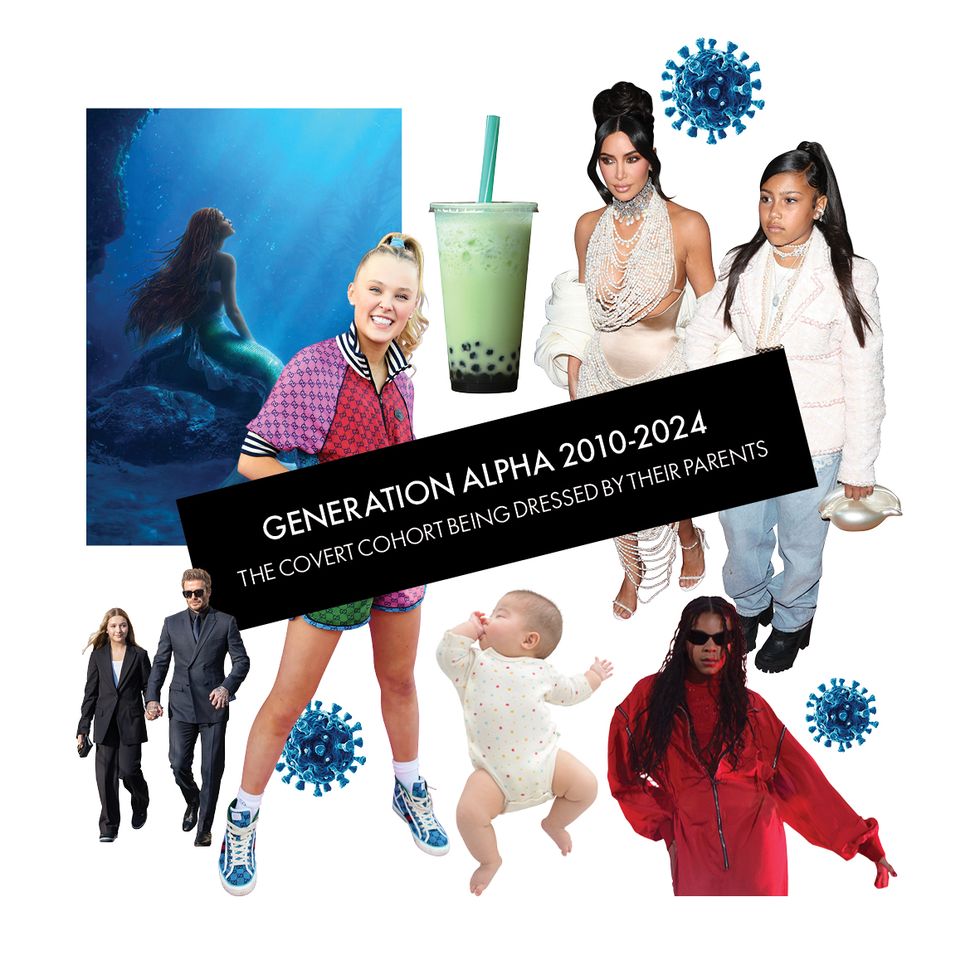

Even Gen Alpha is becoming more crystalised in our minds - those born in the period after 2010 are entering teenagehood and have never really known a world without social media or even VR - making them (frighteningly) the world’s first blended reality cohort.

Generational labels have become enough of a focal point that those who were born in the liminal years between generations have even come up with their own micro-labels - ‘Zennials’ for those in their mid-20s or ‘elder millennials’ for those in their late-30s. Xiennials (for that micro generation at the tail end of X and start of Millennials who don’t relate to either); Pro, Mid, and Nouveau Millennials, Neo Boomers, Gen XS, Gen Xenos - the implication is that their unique position straddling two generations confers a unique set of experiences which they alone can claim.

But despite how much airtime is given to generational labels, and how the rotation of generational labels is gathering speed everywhere from TikTok to sociological studies, they remain dubious signifiers, with critics arguing that they’re about as useful and scientifically sound as star signs.

So what gives? Why and how have generational labels become so ubiquitous - and do they really mean anything? Most sociologists trace the birth of generational labels to the 1800s. Writing in the New Yorker in 2021, the Pulitzer-winning academic Louis Menand pointed out that, by 1800, the term ‘generation’ had been ‘transplanted from the family to society,' he says. 'The new idea was that people born within a given period, usually thirty years, belong to a single generation.

There is no sound basis in biology or anything else for this claim, but it gave European scientists and intellectuals a way to make sense of something they were obsessed with, social and cultural change. What causes change? Can we predict it? Can we prevent it? Maybe the reason societies change is that people change, every thirty years.’

Three hundred years later, 'social media has made it easier to weaponize intergenerational conflict,' says psychologist Dr Paul Marsden. He researches consumer psychology and the impact of tech on different generational cohorts at University of the Arts London. 'And thanks to that conflict, it feels more important to align yourself with one generation over another.'

Of course, intergenerational strife has been around since Elvis’ snake hips turned a generation of teens onto rock & roll, though as Marsden points out, of late, it seems like the rivalries have dialled up a notch. We have, in part, the algorithms to thank for this: social media platforms have been shown to favour and push content which shows conflict and tension (users react more strongly to it).

While for most of the 2010s conflict tended to focus on innocuous trends - the type of emojis one generation uses vs another, for instance. In 2019, a TikTok video where an older man is seen explaining that 'the millennials and Generation Z have the Peter Pan syndrome, they don’t ever want to grow up' served to politicise the whole generational debate.

The retort - 'okay Boomer' - subsequently went viral across social media and became a rallying cry for the world’s disenfranchised youth. As Marsden explains, '"okay, Boomer" was a way of signalling an intergenerational distinction, a way of saying "we are not them, and they are not us"'. A whole movement grew around the phrase. Merch was sold, memes were made and 'okay Boomer' became a shorthand way to tell someone that they were out of touch (and insult an entire generation in the process).

'Gen Z is probably going to be the first generation where things will not be materially better for them, in terms of their life chances, compared to previous generations,' says Marsden. 'And so there was a huge frustration being expressed with that phrase.' Indeed, as many from the ‘Peter Pan’ generations pointed out, they were inheriting an economic (and global) climate that was vastly less hospitable than the ones their older counterparts had matured into.

In the four years since ‘okay Boomer’ went viral, the pandemic - and the culture wars which raged during that hyper-online period - have served to further spotlight apparent differences between generations. At the end of 2021 pollsters BritainThinks conducted a number of studies and focus groups exploring generational attitudes towards everything from identity politics to the NHS.

They found that under-24s cared most about issues such as BLM and trans rights while older generations cared much more about immigration and the economy. It wasn’t so much that being Gen Z automatically made someone ‘woke’ but rather, as Ben Shimshon, co-founder of BritainThinks said at the time, 'lived experience underpins [the] views [of young people]. Thirty-eight per cent of young people say they personally know someone who describes themselves as transgender or non-binary, compared with 14 per cent of over-25s.'

As Marsden explains: 'Clearly lived experiences will impact how people develop their worldviews and sense of self. Take Gen Z, for instance, they grew up around the period of the financial crisis and this has had a big impact on that cohort - they’re actually more materialistic than other generations were at their age. They are also more environmentally concerned because, in their formative years, it was on the educational agenda whereas for previous generations it wasn’t.'

In fact, the socioeconomic conditions that younger generations have inherited may also explain why generational labels have come to feel more important. 'Issues like the climate emergency and the housing crisis have made it much easier to look at the world through the lens of intergenerational conflict,' says Marsden. 'It feels like we need to find someone to blame for how things are.'

And as the issues we’re arguing over have gotten bigger, more serious and more existential (hello, the literal death of the entire planet), categorising ourselves as part of one generation or as different to another has become not just a way to express trite differences of style but also a shorthand, signalling which beliefs we align ourselves with, which we don’t and which particular challenges we’ve faced.

Of course, many researchers believe that generational labels simply aren’t useful. And, in fact, the creation of ‘micro-generations’ like Zennials seems to highlight the arbitrariness of the whole concept of a generation. In 2021, the American sociologist Philip Cohen, even wrote an open letter calling on the Pew Research Center, one of America’s main polling organisations, to abandon generational labels altogether.

Part of his argument against them was that generations 'have been declared and named on an ad hoc basis without empirical or theoretical justification' and that 'naming "generations" and fixing their birth dates promotes pseudoscience, undermines public understanding, and impedes social science research.'

Basically, given that the point at which one generation ends and another begins is completely arbitrary, how can we reliably say that being born in 1968 (Gen X) vs 1998 (Gen Z) will have any kind of material impact on us? In his book The Generation Myth, Professor Bob Duffy, a social scientist at King’s College London argues that rather than any genuinely robust science or data, we have the polling and consultancy industries to thank for promoting the use of generational labels.

They sell oversimplified takes to brands desperate for any insight into the behaviour of their consumers (or future consumers), which are hard to disprove but which, he says, are often divorced from reality.

Emily Chapps, a senior creative strategist at branding agency MORNING, doesn’t disagree that generational labels are often used as shorthand by marketers to interpret consumer behaviour; but argues that they do offer-up some useful insights into shifts in attitudes and contexts, especially thanks to rapid advancements within tech. 'I think since the mid-1990s, we've had a revolution in the way people communicate or the way they consume their culture every few years.

'Think about what you learned in IT, for instance, when you were at school,' she says. Excel spreadsheets and data entry, mainly (what? I’m old). 'Exactly,' she laughs, 'the generation who are in school now are learning to code. Millennials had the first wave of the internet, Gen Z have a matured version of the internet and Gen Alpha, are online all the time - their lived experience is a much more seamless blend of real life and digital.'

The way that people use tech has also changed. Millennials needed institutions and systems to provide the tools, Gen Z used the tools themselves and Gen Alpha are learning how to create their own tools. All of which, argues Chapps, makes for a degree of commonality as each new wave learns the same tricks and techniques to construct and manipulate their digital world.

The rapid cycles of advancements that we’re living through might also be part of the reason that we’re more desperate than ever to band together - even if those bands are considered arbitrary by some. 'It is a chaotic, complex world out there,' says Marsden, 'and we - as humans - are constantly on the lookout for ways to simplify it. We put stimuli, whether that’s people, objects, or whatever, into categories and give them a label as a way to make better sense of our experiences.'

The act of labelling, whether that label is truly representative of all the people it attempts to capture, can also be a useful way for us as individuals to shore-up our sense of self. 'Our identity is made up of multiple layers, there are the things we do ourselves that make us unique but our identity is also created and bolstered by the groups with which we identify.'

There is of course only so far this kind of simplification can take us and as Chapps points out, younger generations in particular resist the idea that they can be flattened into one catch-all label. 'In terms of their views, Gen Z are much more diverse than Millennials,' she explains. ‘So you find that among that cohort there’s a distaste for things like generational labels.’ Marsden agrees: ‘Gen Z is the most diverse generation we've ever had in terms of their values, their identity and their behaviours. And so there's this reaction you get like, “you can’t put me in a box with a sixth of the rest of humanity, I am my own self".’

‘It’s an attitude of, “you don’t know me”,’ says Chapps. ‘Particularly compared to Millennials, who had a lot of "tropes" which they were quite comfortable with (from performative activism to brand logos), Gen Z are on the whole more individualistic. Of course, you kind of have to remember that the majority of Gen Z are teenagers - so there’s a degree of teenage angst in that.’ And as generation Alpha enter adulthood, there’ll be a whole new set of tropes (or anti-tropes) to contend with - though, I’d argue that the quest to find and follow a dream will remain a constant. Just maybe not tree surgery…

This feature was originally published in the October 2023 issue of ELLE.