The day I scattered my mum's ashes, I fell headfirst into a canal. I was walking back from the cemetery to spend the night with a friend who lived in a canalside flat. As I tried to find my way in the dark, I took a wrong turn and plummeted into the water. It was the most ridiculous moment of my life, made funnier by eventually being pulled out by two men on a stag do. The absurdity of it makes for an easy anecdote to pull out whenever I feel like a laugh is needed, or there’s a lull in conversation.

Most people assume I was drunk, coming back from a night out. What I always neglect to say is the reason why I didn’t see the dark, icy stretch of water in front of me is because my eyes were swimming with tears and my head was spinning with the sight of my once living, breathing mum – who’d once wrapped me in tight hugs and wiped away my tears with warm fingers – being swept away on the wind as tiny pieces of grey dust.

The ‘canal incident’, as I refer to it now, typifies grief for me. Grief is giddy, dizzying highs and crushing, startling lows that consume your body. These are the emotions I’ve come to associate with Christmas. And, in 2020, they've reared their head in an even greater intensity.

As Covid has upended our lives and daily death figures filled our phone screens, I've felt the familiar dizzying, rootlessness course through me: the foreboding of raw grief. Friends have spoken of life feeling surreal, of time becoming abstract, of starting to define moments in their lives as being ‘pre-Covid’ or ‘post-Covid’, just as I had come to define memories as ‘before Mum died’ or ‘after Mum died’.

Throughout autumn, talk of Christmas escalated into hyperbolic headlines and a maelstrom of opinions from scientists about how or if we should see our families. Last weekend, Boris Johnson announced the tightening of restrictions over Christmas, acknowledging how important it is ‘for families to be together’ and how ‘disappointing’ the news rules will be. But, as festive family reunions began to shape our national politics, I've felt even more isolated from the conversation. For me, Christmas changed forever a long time ago.

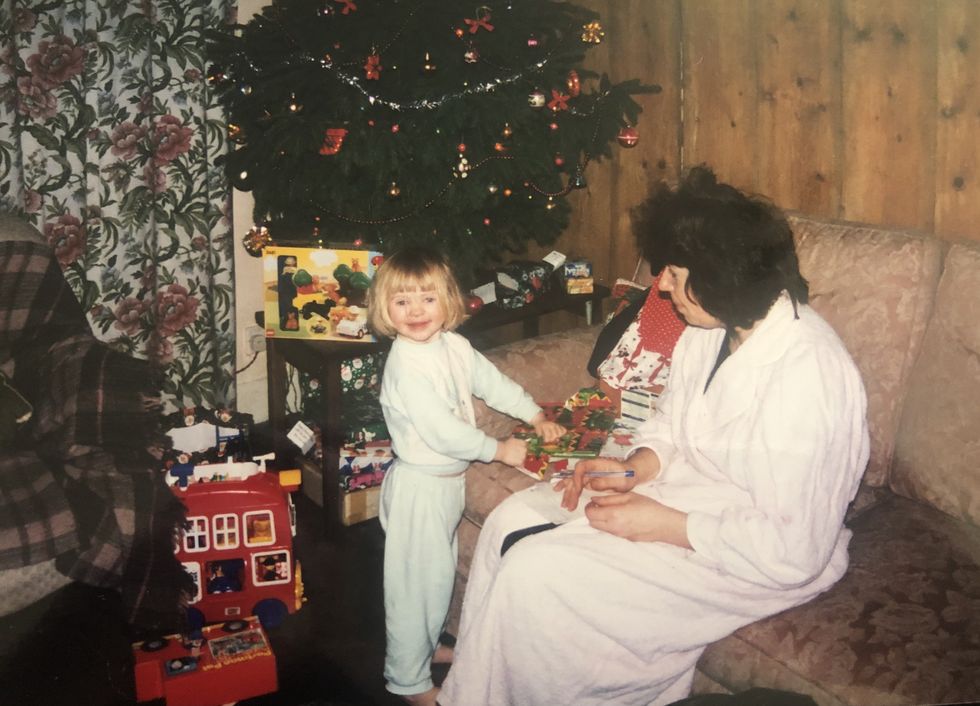

Growing up, my family Christmases were defined by rituals. Each one was a small, comforting constant that my tiny family – just Mum, Dad and I – could rely on each year, while the rest of life inevitably shifted and changed. Each year my mum and I would make wishes over the Christmas cake mix (‘Richard Gere under the tree,’ she'd cackle). She’d stuff the house with so much food that each December someone would open a kitchen cupboard and risk being hit with an avalanche of mixed nuts.

My favourite ritual though was finding a bauble in my stocking every Christmas morning, which had been carefully picked out by Mum. Some were kitsch and gaudy, like the cock-eyed sequinned reindeer. Some reflected my fleeting childhood obsessions, like the porcelain ballet shoe. But, mostly they were small, fragile things, delicate hand-blown angels or glittering glass birds – ‘Beautiful, like you,’ she’d say – and it became tradition to ceremoniously hang each new trinket on the tree together.

Even after my parents divorced and my dad moved back to the US where he grew up, our traditions held strong. Mum and I still had the same argument about whose turn it was to drag the decorations out of the loft and our annual tipsy singalong to the Top of the Pops Christmas special remained a fixture. What I remember most is the feeling of being with her under the soft glow of fairy lights, feeling cosy, warm and loved.

By the time I started university, my mum had survived cancer twice. When I moved from my hometown in Yorkshire to university in London, I presumed she was invincible. Then, when I was 19, everything crumbled.

I got a call from my mum telling me to come home as soon as I could. Her cancer had returned. Within a fortnight, I was sitting by her hospice bed watching her take her last breaths. A month later, I boxed away all our furniture. There was no time for tears. In the rush to clear the house so I could sell it before I went back to university, our Christmas bauble collection was swept away in the deluge of boxes – lost forever.

That year I spent Christmas with my dad in Oregon for the first time. It felt like a greyscale simulacrum of the Christmases I’d known before, where everything, from the unfamiliar baubles on the tree to the strange American scenery outside, only amplified my mum’s absence. It was a new Christmas, in a new country; one where I couldn’t find the old feeling of being safe and loved. I went to bed that Christmas Day and cried until I felt empty for the first time since my mum died.

I grew to dread Christmas. I avoided celebrations, and refused to put up decorations. Twice I worked on Christmas Day and spent the dark winter evenings until New Year curled up alone in my flat. I resented the pressure to be happy when my whole world had disintegrated. The bright lights, songs claiming this was ‘the most wonderful time of the year’ and frenzied present-buying seemed to mock me. Friends talking about plans to be with their families filled me with rage and jealousy. December, with all its glitzy trappings, became a constant reminder of all the Christmases my mum, who died aged 59, had been cheated of.

The festive period will always magnify my grief. Flickers of envy still erupt when I hear people chatting about family plans. But, over the years, I’ve slowly turned my attention to other celebrations that don’t revolve around family. I've relished the hedonism of the office Christmas party and counted down the days until Christmas Eve drinks at the pub, where my friends and I swap our annual £2-limit Secret Santa.

There are still days when all I want is my mum, and this year they’ve come thick and fast. For the first time in years, I find myself calling her mobile and pretending to talk to her through the blare of the unrecognised-number tone. I spend hours stalking my old family house on Google Maps, like I did addictively after it was sold.

With Mum gone and Dad 5,000 miles away, this year I've felt lonely, but I’m grateful not to have been swept up in the fear and confusion of this winter. I’m used to Christmas Day not being one of reassuring rituals, but uncharted territories.

Over the years I’ve spent Christmas travelling up and down the country couch-surfing between various friend’s houses. Since meeting my boyfriend, it’s been spent at his mum’s house where we’ve luxuriated in the break from work. Gradually, I’ve grown to enjoy the unknown adventure Christmas has become. In this way, I’m probably better prepared than most for the anxious, tumultuous day that 25 December 2020 will be for many.

This Christmas will be the ninth without my mum, and things will be different again. I’ll be staying in my flat in London with my boyfriend, where his mum not being here with us will mark another absence.

For those grieving, Christmas will always be a painful time. The most important lesson I've learnt is to treat ourselves with kindness at this time of year. After all, we only feel such intense pain at being separated from our loved ones – whether it’s through death, or by a window – because we are lucky enough to have experienced unconditional love. While it might be the kind of love that leaves searing holes in our hearts when our loved ones aren't as close by as we'd like, it's also the kind that makes us hopeful for the future and of the countless more warm embraces to come.

Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.

In need of more inspiration and thoughtful journalism? Subscribe to ELLE's print magazine today. SUBSCRIBE HERE