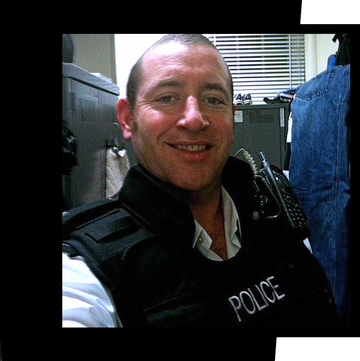

There's a pot on my windowsill. To the untrained eye it is nothing special. In fact, it’s quite bland looking. Misshapen. Unfinished. I made it last summer in a pottery class where I met someone who I wasn't expecting to meet, after so long in lockdown solitude. Someone with whom I ended up having a short and, for the most part, wonderfully intense relationship.

First appearances deceive many. Have you heard that saying? I think about it a lot. Dig a little deeper, behind the blandness of a surface, and you'll likely find a more complex emotional terrain. I thought about it again whilst watching an episode of Modern Love’s second series, 'On a Serpentine Road, With the Top Down.'

The opening scene paints a half-picture: a woman (Minnie Driver) in motion; meandering empty streets, head-bobbing to 'Peace Frog' by The Doors, looking ahead. Free. And yet, the picture is expatiated on, as you learn that this is not her vintage convertible, it belonged to her late husband. It is one of the few precious items she has left of his, that keeps his memory, and the love they shared, alive. Faced with the prospect of soon having to let the car - him - go, it is one of the most heart-breaking and humbling thirty-three minutes of screen time I’ve consumed this year.

As Driver says at one point, this car is not merely a vehicle but a time machine: 'It literally transports me.' As someone who self-identifies as both a hoarder and hopeless romantic, I hard relate. To be clear, I’ve never had to deal with the unending grief of losing a partner who has died, but I have lost love. And in stark contrast to the cleansing post-breakup rituals many preach and practice, I believe objects that weave you back to a sweeter time, when a feeling was untouched by the sting of its demise, are souvenirs worth keeping.

Over the years, I’ve accrued various memorabilia from the ghosts of relationships past. A battered box full of decade-old handwritten letters from my first boyfriend, full of longing and horniness and bad poetry. An old woollen hat that an American artist, in London temporarily for a summer programme, gave me towards the end of a whirlwind romance in my early twenties; before the reality and frustration of our living on different continents had properly set in. A velvet vintage jacket an ex bought me for my 27th birthday, that somehow always feels a bit too special to wear to anything.

While these artefacts prompt different reflections, they all anchor me to something real. Time can be unkind to our memories. By their nature, they shapeshift and become diluted days, months and years later. When it no longer pains you to not see that person, or their name pop up on your phone screen, their faces, the conversations you had, the details gradually start to disappear. But through my collectibles, I have it: Proof. That - for a moment - I had something wonderful. It takes me back to those infant bolts of desire when you first meet someone. A stranger laughing at a remark you made about Ghost, say, and later teasing you about your poor attempts at pottery. I see him, yes, but on a much grander scale, I see me. A past version of me boundlessly open to the possibility of something - or someone - new.

Cultural conjecture, or even those close to you, often tells you that to cling to all this ‘stuff’, holds you back from truly moving on. See a season one Friends episode when Phoebe encourages Monica and Rachel to partake in a ‘ritual’ to break the bad boyfriend cycle (A.K.A. burn anything that’d stir up the pain of a past relationship). It’s explored intensely in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, whereby Joel wishes to erase Clementine from his memory (as part of a medical procedure to do so, he presents objects associated with his ex – photographs and gifts – he wants to forget). Though, as Joel slowly comes to realise, this is a futile exercise, and that he would rather have pain and pleasure be bedfellows in the narrative of his life, instead of banishing pain from view. Because you cannot truly have one without the other.

Love and heartbreak: both have shaped me and course through my connections in innumerable ways. So, no, I don’t think cherishing symbols of a former flame dampens the embers of a present or future one. It’s more an act of self-service, than a refusal to let go. It's a reminder of your capacity to let another person really see you. And that that feeling is achievable at any point in life. That it is always worth it in the end.

I smile thinking about a book, Heartburn by Nora Ephron. I posted a copy of it to Pottery Guy on his birthday last year, underlining my favourite quote in it, where somebody asks the protagonist – broken and confronted by an uncertain future without the husband she had planned to spend the rest of her life with – do you believe in love? Her scepticism threatens to overwhelm her, but she arrives at a simple conclusion.

'Yes,' she says. 'I do.'