In a specially constructed bubble building on the banks of the Thames last October, Alexander McQueen presented its typically future-facing vision of luxury for spring/summer 2023.

Amidst the spectacular gowns and sculptural suiting was a pair of bumster jeans. Nothing that remarkable to modern eyes, although the hip-revealing cutaway denim body with which those jeans were worn would certainly turn heads. Such is the ubiquity of denim in the world of luxury these days that there were nearly 1,500 iterations on the catwalks last season – incredible even by recent standards. No wonder we have lost sight of just what a strange development this is.

Jeans in their workaday origins were the antithesis of luxury. If you had suggested to a 19th-century lady who lunched that she might wear an item of clothing known only as the pseudo- uniform of cowboys and gold-rush miners, she would have recoiled in horror. For her 21st-century equivalent, however, jeans are a pseudo-uniform, too. Indeed, jeans have become so universal across all ages, socio-economic classes and locations that future historians may well label ours the Denim Age.

Like pretty much everyone else I know, I have a thing about denim. I have several pairs of jeans, and I wear them often, my current favourites are a vastly outsized style from Raey that I wear with a neat cropped jacket or knit. I often wonder why, when I am lucky enough to have the riches of a fashion director’s wardrobe to pick from, it is so often to jeans that I turn.

I didn’t during lockdown, needless to say. Like the rest of the world, I found the allure of an elasticated waist hard to resist, not least because I also found the allure of a nightly packet of truffle crisps difficult to resist. But jeans are back in pole position for me, not to mention the rest of the fashion pack.

Why? Because in a funny way, they can feel and look quite dressy after track pants. They can certainly add structure, especially if you avoid stretch styles. The jeans devotee and stylist Angie Smith says the weight of the denim is key. ‘It’s about wearing something that is going to give you a straighter line,’ she says, ‘so if you have got a curve, add a bit of straightness to it, and if you have got straightness add a curve.’

As I write, the most expensive pair on Net-A-Porter are black and feather-trimmed from Valentino, at £1,790 with a crystal-embellished blue Mugler pair just behind at £1,780. Ladies who lunch like – and wear – jeans just as much as the rest of us these days.

Even at establishments such as 5 Hertford Street, the upscale London private members’ club, jeans are allowed, albeit not those ‘with considerable rips or frays’. Though what if those ‘considerable rips’ come with the imprimatur of Givenchy, which showcased some jeans for AW22 that were, in truth, more rip than jean? I can’t help suspecting the management might turn a blind eye.

How peculiar this all is, not least because of the peculiarity of jeans themselves. Here is something that was very precisely tooled for their original user, thanks to their indestructible fabric. It would have been impossible to predict, when jeans were first developed in the second half of the 19th century, the degree to which they would transcend these origins. Yet it’s in part this very origin story that has enabled them to do so.

The frontiersmen who wore jeans became, courtesy of Hollywood films, akin to mythological figures in the 20th-century collective consciousness. They were associated with all that was free, wild and – until a more nuanced reading of America’s problematic ‘founding’ story supplanted this one – true.

Next up, Hollywood fixated on a new hero, also free and wild, and at his core – it was always a ‘he’ at this point – an extrapolation of those earlier ones. Here was a variety of hero only newly invented in society at large: the teenager or young adult, a phenomenon not recognised as existing before the 1950s. Youth became one of the most potent, and commercially leverageable, forces in our society, and remains so to this day. And from the start, its clearest signifier was denim.

We wear denim today because we want to look and feel young, at a point in history when youth has more sociocultural heft than ever before. We also wear denim because ours is a society that purports to rate nonconformity; to admire rebels without a cause. That we should choose to signal our nonconformist status with a piece of clothing that has become, as discussed, the ultimate manifestation of 21st-century conformity only serves to underline some of the inconsistencies that lie at the heart of our culture.

Which brings me back to another contradiction: the retooling of the ultimate everyman item by luxury brands – see those Mugler jeans with crystals, or Gucci’s long-ago feather-and-bead-pimped style from spring/summer 1999. The latter was a collection dubbed by Tom Ford, the brand’s designer at the time, ‘Las Vegas hippie’. A Las Vegas hippie? Yet one more contradiction in terms. Contemporary fashion is all about making a new whole out of apparent opposites, however; about squaring the circle, or indeed circling the square. Denim – especially the luxe variety – offers myriad routes into doing that.

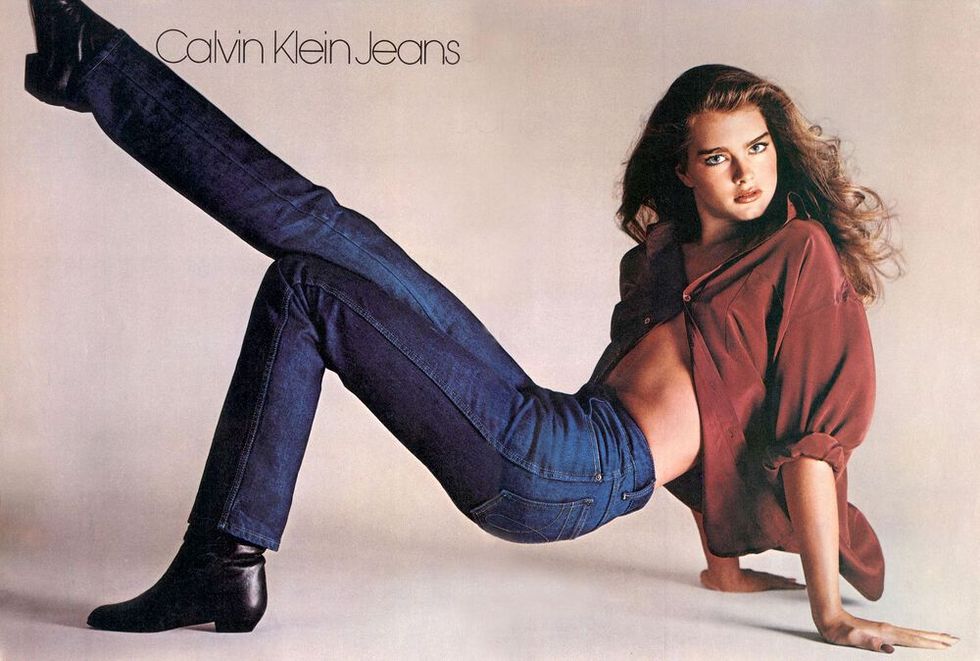

Then there is the idea of jeans as a second skin, which found its fullest expression in Brooke Shields’ famous advert for Calvin Klein in 1980, in which she declared, ‘Nothing comes between me and my Calvins’. This, in turn, played into the notion that jeans are not merely easy to wear, but almost an extension of who you are. They were invented purely to be functional, regardless of price. And that functionality has, almost two centuries later, extended into every aspect of society.

Luxury today is about specialness, just as it has always been. But it is also about movement, to a degree that it didn’t used to be. Luxury can no longer afford only to be a noun. It has to be a verb, too. And denim was the harbinger of that change.

Anna Murphy is the fashion director of 'The Times'. Her book 'Destination Fabulous: Finding Your Way to the Best You Yet' is out now.