A good friend of mine left my life recently. She hasn’t died or anything, she just doesn’t want to be friends anymore. I can’t say why for sure. Perhaps lockdowns pushed us apart, or we outgrew one another – or maybe the friendship was exactly how it was meant to be: intense and inevitably transient. As the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu wrote, ‘The flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long.’ Amy and I sure were on fire. This friendship fling was an unrivalled cocktail of adrenaline; we polished one another’s sentences as we discussed the book we’d just read, laced with dopamine hits of frantically messaging back and forth late into the night, and finished with a kick of oxytocin when she’d show up at my place, tote bag filled with groceries, insisting she cook me pasta after a particularly tough day. But on some level, perhaps I always knew the relationship would be – like many things in life – fleeting. Yet it’s left me feeling stung.

Julia Samuel is a leading psychotherapist and author who focuses a lot of her work on change and transience. Her forthcoming book is called Every Family has a Story: How we Inherit Love and Loss. She tells me, ‘There is a lot of pain, sorrow and distress from female friendships that come to an end.’ She suggests this links directly to narratives constructed by the media and the way it’s projected on screens. ‘The culture is informed by TV shows and films where a group of women are amazingly close, they support each other through all life’s phases and they have all the fun. But of course, where you have people, you have complexity.’

Dr Sophie Mort, clinical psychologist and bestselling author of A Manual for Being Human, says these narratives speak to ‘they lived happily ever after’ scripts: ‘Think of the lobsters and the penguins of the world who mate for life, and the elderly couple, who were childhood sweethearts, holding hands – they have been the poster children for romance. The romantic notion of permanence is what most of us grew up with and is the idea many of us believe we should strive for. These ideas come from society. They shape what we think we need, but in reality transience is not a bad thing.’

The reality is that we have different types of friendships with different types of women in different times of our lives. But if longevity is most prized in platonic relationships, then anything other than a decade’s worth of nights out, late-night phone calls, in-jokes, drunken confessions and expensive city breaks seems, well, pointless.

My short-lived intense time with Amy taught me that passing friendships should be celebrated for what they are, rather than seen as some kind of failure when they fizzle out. These are the friends you make when you become a new parent and want to latch on to an NCT mum who will also moan about their baby and their selfish resistance to sleep; or that colleague who has learnt to monitor the subtle fluctuations of your mood and knows exactly when you need a KitKat; or perhaps it’s the woman you met on an Intensive Spanish evening course, with whom you find yourself drinking red wine late into the evening and planning a month in Madrid together that you both know is never really going to happen. These relationships can get deep, niche or codependent very quickly. There’s an inbuilt unsustainability to them – but isn’t that part of the charm?

The French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote, ‘Modernity is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immovable.’ If we embrace them, transient friendships are an important half of our social lives. But this is easier said than done because, the truth is, I’m still feeling sad about my recently extinguished flame with Amy and have been left confused in its smoky residue. There was no fight or dramatic end, which makes it even harder to process.

I speak to my best friend, Lydia. Outside of my family, she’s the most permanent and immovable person in my life and we’ve been inseparable since we were 13. She reminds me that something lasting like ours is the perfect backdrop for more wavering attachments. She says, ‘Our friendship is so deep, simple, eternal. It’s like sisters. Our closeness complements and provides space and ease for more transient friendships. They’re made clearer and more defined by existing around what we have.’ Lydia is definitely comfortable with fleeting friendships, so I talk to someone who also found them more difficult.

Viola is a jewellery designer who has had such a hard time with transient friendships that she’s in therapy trying to unpack the turmoil they have left. She finds it very difficult to talk about the evanescence of these interactions and that word ‘failure’ rears its judgemental head again. ‘These friendships have felt like two disco dancers crashing into a new world together,’ she says, ‘having all of the laughs at all of the parties and then falling out over who knows what before we f*ck off in different directions, crumpled, humbled and licking our wounds. I have never thought of these friendships as transient. Perhaps referring to them as transient, rather than failed, is a good place for me to continue from.’

When I ask Viola to pinpoint what it is that makes the ending of these relationships so complicated, she thinks it is the burden of ‘forever’. She says, ‘It’s born out of Disney films, friendship bracelets, two halves of a love heart, pinky promises, BFF hashtags, gossip and matching life goals, but it often doesn’t look like that. I rarely tread lightly when I make a new friend who I think is wonderful. This level of intensity means that the highs are brilliant and the lows unbearable.’

This means we forget the real complexity of human nature. Julia Samuel says, ‘If you have this assumption that a good friendship with another woman is only good if you’re constantly in contact, if you tell her everything and she tells you everything, then it’s very unlikely you’ll get your needs and expectations met. Some of us want to be a particular version of ourselves with this particular woman in this particular time and that’s the delight of having different people in our lives.’

There’s an appealing casualness about fleeting friendships and less pressure, as they do not need as much maintenance. They’re less like a plant needing nourishment, pruning and constant watering, but more like a gorgeous bunch of flowers you choose for yourself, vibrant and colourful, with rarer stems that will inexorably wilt and die. So why does it often feel so bad when they come to an end?

With long-term friends, our personality, to an extent, solidifies; it’s harder to deviate when they know our quirks and neuroses. I miss the version of myself I could be with Amy; the parts she stimulated and gave me access to. She excavated a confidence I’d lost sight of, she played strings in me that were more carefree and channelled courage that helped me set up a business. She reminded me to not take life so seriously and then – as I let my hair down and got lost in myself, swaying under the disco ball – my dancing partner exited the scene.

I decided to get in contact with another friend I’d drifted apart from, in the hope that speaking to her about our mutual untethering would shed some light on the concept of the BFFN (Best Friend For Now).

Rebecca is a radio producer and she lived in the flat downstairs with her girlfriend, Holly. When I moved into the building, I liked them both immediately. I used to adore listening to them cooing at their cat, Otis, or screeching with laughter as I dragged my shopping up the stairs. They smoked like chimneys and seemed to have two default modes: hilarious and kind. They weren’t like a lot of my friends in that we never spoke about work – the thing I most defined myself by. I felt so light around them. I could be silly and say things I wouldn’t usually in front of people who had preconceived ideas of me. Julia Samuel praises this freedom offered by transient relationships: ‘You can be a new version of yourself. You don’t have a history and they don’t have a pre-expectation that you’re going to be a particular way. It’s liberating. You can make a different present and future with someone who sees you in this new light.’

Having moved out over a year ago, Rebecca seemed pleased to hear from me. When I asked if we could talk about the transmigratory nature of our friendship, she was happy to get into it. ‘At first, we only knew each other as neighbours, saying a fleeting hello at the front door and having a shared cigarette, but after a few short weeks, we developed a friendship that was pretty rare and unexpected. There was a lot of trust – we knew we could rely on each other to help out with house and pet-sitting, or when one of us got locked out.’ I laugh at a memory of me drunkenly mounting a bush and pitifully calling out their names, nose pressed against their bedroom window. ‘We spent time together, having dinners, talking about our lives, and we even met each other’s friends and family. The relationship became particularly important through lockdown and sometimes you’d be the only other human we would see in a day. I was very appreciative of you throughout that time.’

I feel nostalgic about our friendship, too; the late nights in my flat, candlelit dinners around a coffee table on the floor as we opened another bottle of red, laughing at Holly’s latest escapade, like the dog she’d rescued that day using her dressing-gown belt. And yet, when I moved out, it came to a natural end and none of us had any expectations for it to continue. ‘I don’t think I ever really thought about how long the friendship was going to last, but you never really do, I suppose. It moved on naturally, because you moved out. I think the relationship would’ve been a completely different one if we weren’t living next door to each other.’

Rebecca is very positive about transient friendships. She says, ‘I think we should be more accepting. Things can be perfect for a certain time and then it’s healthy to let go.’

I seek out more women who’ve had positive experiences of temporary friendships and I stumble across Margot, a 40-year-old graphic designer, at a party. She says, ‘Over lockdown, my neighbourhood WhatsApp group became a real lifeline. Someone I’d never met before asked the group if anyone could print something for them and I offered. As soon as I opened the door to this person, I felt the thrill of a connection. Immediately, I realised he was a fabulous individual who worked in fashion and, having been starved of seeing my friends for so long, we ended up having a meaningful conversation on my doorstep. We would go for weekly walks – I am almost twice his age, but it didn’t matter – and we shared our life stories. It felt like I was reminding myself of who I was when we spoke. ‘Once the world opened up again, our walks stopped and we rarely messaged. We still live opposite each other and pass each other in the street with a quick hello. We served a purpose for each other at the time and there is an unspoken agreement that neither of us need that kind of intimate relationship now we can connect with our real friends again.’

Julia Samuel says, ‘We know from research that even a five-minute chat with the person you buy your coffee from can be an important connection. A relationship that lasts a number of days, weeks or months can be meaningful and feed your sense of self and your sense of belonging, as well as expanding and changing your view. Longevity isn’t the be all and end all.’

Throughout my adult life, I’ve shared many significant moments with people who ended up being minor characters: colleagues who were my closest confidantes, wrapping arms tightly around me as I grieved; women in flatshares who knew every intimate detail about my sex life and now probably couldn’t remember my middle name. I’ve been giving these connections the back bench, treating them as substitute players who were just warming the seats for the real thing, but I’ve been wrong about them, restricting myself from accepting the real depth of that encounter and what it offered, because it eventually ended.

Dr Mort tells me that some humans deal in transience more than others, but ‘these sorts of relationships can be profound, even life-changing. The ending of the connection does not negate the importance of it. And not all endings are forever.’ If I can remain open to the fluctuating nature of friendship, who knows who might be around the corner, waiting to form a new temporary and life-affirming bond?

She explains, ‘Almost everything in our lives is impermanent: humans do not live forever; emotions rise and fall; flowers bloom and wilt. We hate to admit it, but it’s true. When we are able to recognise that almost everything is transient, we can appreciate each moment in our life for what it actually is. We can enjoy the bloom of each temporary bud and be delighted should someone stick around longer than we expected.’

I think about reaching out to Amy, but in the end I don’t, because our ending is simple. Not everyone is meant to stay in our lives forever and this doesn’t degrade the friendship, its relevance or its significance. Sometimes, special people are only meant to have cameo roles, so instead it’s time to bed in with the most loyal and steadfast chum of all: I choose to befriend transience.

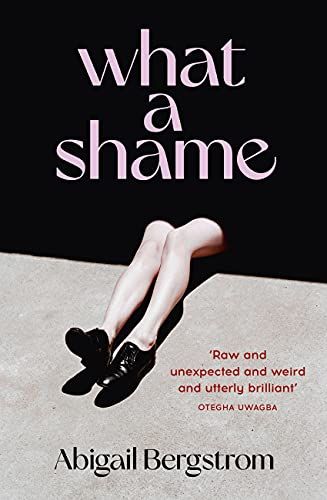

Abigail Bergstrom’s debut novel, What a Shame, is out now.